Tulare Lake, in California’s San Joaquin Valley, was once the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River. The lake would grow every winter as rainfall and snowmelt from the nearby Sierra Nevada range flowed down and filled the basin. By 1920, the rivers that fed the lake were dammed and diverted for uses such as irrigation. Since then, the lakebed has been covered with farms that grow a variety of crops.

Heavy rain and snow in the first three months of 2023 has once again brought water to Tulare’s lakebed. On March 29, 2023, the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on the Landsat 8 satellite acquired this image (above-right) of agricultural fields near Corcoran covered with water. The image is false color, which makes the water (dark blue) stand out from its surroundings. Vegetation is green and bare ground is brown. The image on the left, acquired by the Operational Land Imager-2 (OLI-2) on Landsat 9, shows the same area in March 2022.

With a population of 22,000 people, Corcoran is the largest city in the vicinity of the historic lake. Many homes in the city have been flooded and several roads have been closed. Smaller towns to the south, Allensworth and Alpaugh, were surrounded by water from overflowing rivers and were both under evacuation warnings as of the end of March.

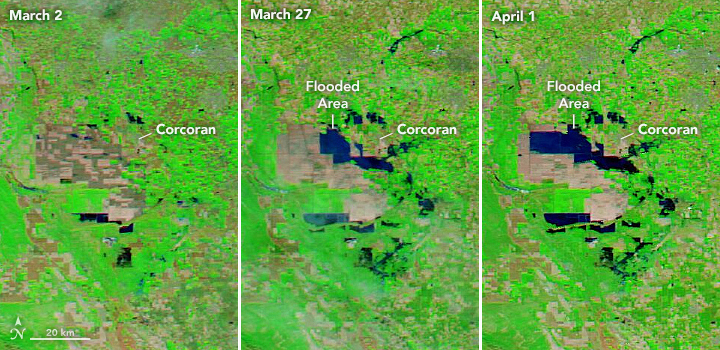

These images show a wider view of the Tulare lakebed. They were acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite and show the progression of flooding between March 2 and April 1. Two successive atmospheric rivers hit California in March 2023, contributing to flooding along the San Joaquin River and a breach of the Los Angeles Aqueduct.

“The Tulare basin floods occasionally, especially during extremely wet years and years with abundant snowpack on the Sierra Nevada mountains,” said Safeeq Khan, agricultural engineer and adjunct professor in civil and environmental engineering at the University of California, Merced. Khan noted that the lakebed flooded in 1969, 1983, and 1997. Until this year, 1969 and 1983 held the record for the wettest years with near-record levels of snow in the region.

“The basin is a powerhouse for agricultural production and the impact of the flooding is going to be prolonged,” Khan said. “The four counties within the basin—Fresno, Kern, Kings, and Tulare—are some of the top-producing counties in the state.” Khan also serves as an extension specialist for the University of California’s Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources (UC ANR), which helps connect farmers, industry, and communities with the latest scientific research.

As of 2022, the lakebed contained farms that produced cotton, tomatoes, dairy, safflower, pistachios, wheat, and almonds. According to the Western FarmPress, the floods in spring 2023 have forced numerous dairies to relocate cattle from the region.

Flooding in the region may not let up in the coming months as snow melts from the Sierra Nevada. A snow survey by the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) on April 3 found the statewide snowpack was 237 percent of average for this date, among the largest ever recorded. The size and distribution of this year’s snowpack is posing severe flood risk to some areas of the state, according to DWR, especially in the San Joaquin Valley.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Emily Cassidy.