The name Lake Erie is believed to have originated as a shortened version of erielhonan—a word meaning “long-tailed cat” in the language of the Iroquois tribe that once lived along the lake’s southern shores. The name was likely a reference to the fickle, unpredictable, and sometimes violent behavior of the eastern cougar. Those characteristics are shared by the lake.

“You can have water that is as calm as a pond one moment. Then, within minutes, groups of huge vertical waves can be smashing down on you separated by intervals of just a few seconds,” said Kevin Magee, an engineer at NASA’s Glenn Research Center. “The shallowness of the lake actually makes the waves worse.”

“Storms and waves are probably the number one reason ships sank in Lake Erie,” said Magee, the co-founder of a Cleveland-based group of underwater explorers (CLUE) that search for Lake Erie shipwrecks. Other common causes of foundering here included collisions and fires. “In fact, we think Lake Erie has a greater density of shipwrecks than virtually anywhere else in the world—even the Bermuda triangle.”

Because of incomplete record keeping, nobody knows the exact number of shipwrecks that have occurred in Lake Erie, but estimates range from 500 to 2000. According to an Ohio Sea Grant project that documents many of the lake’s shipwrecks, 277 wrecks have been discovered so far. They are distributed widely throughout the lake, but the western part around Toledo, the Erie Islands, and Cleveland is particularly dense with known wrecks.

The image above was captured by the HawkEye sensor on the SeaHawk CubeSat on November 8, 2020. Weighing just 5 pounds, the toaster-sized satellite is considerably smaller than previous satellite missions that have measured ocean color, such as NASA’s SeaWiFS mission. But despite its size, the multispectral HawkEye sensor will provide ocean color data and imagery of gulfs, bays, fjords, estuaries, and other shallow coastal areas with eight times the resolution of SeaWiFS.

Lake Erie consists of three distinct regions: the western, central, and eastern basins. This image is centered on the western basin, the shallowest part of the lake. With an average depth of just 24 feet (7 meters), this area is especially hazardous to ships because it features several rocky outcrops, shoals, and islands. (Lake Erie’s average depth is 60 feet; Lake Superior’s average depth is 149 feet.)

Among the obstacles is Kelleys Island, about 10 miles offshore of Sandusky. Like all of the small islands in this area, there are several nearby shipwrecks, but Kelleys began to attract extra attention when Tom Kowalczk, a member of CLUE, discovered the remains of what may be the oldest wreck in Lake Erie. The Lake Serpent disappeared near Kelleys Island in 1829 after picking up a load of limestone.

The lighter swirls in the lake are plumes of sediment churned up by storm winds and discharged by rivers. During the same week the image was captured, powerful winds produced a standing wave called a seiche that pushed so much water and sediment to the eastern side of the lake that water levels rose 7 feet (2 meters) in Buffalo even as they dropped by 7 feet in Toledo.

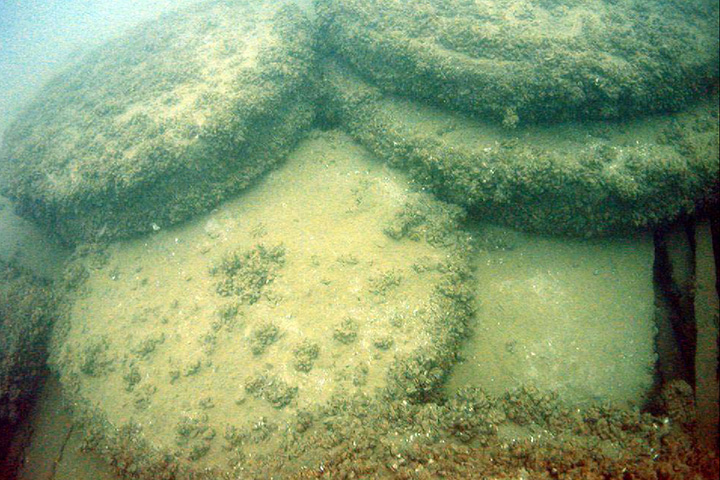

The photograph above shows a railing on the Sultan, a wooden cargo ship that went down in shallow waters about 8 miles northeast of Cleveland. The 127-foot brig was ferrying grindstones (below) to Buffalo in 1864 when it scraped a sandbar near the mouth of the Cuyahoga River during a storm, drifted and took on water for a few hours, and then capsized under the relentless pounding of waves. The ailing vessel sank about 3 miles offshore, descending 43 feet to the lake’s muddy bottom, where the remains can still be found today.

“One of the remarkable things about Lake Erie and Great Lakes shipwrecks is how well they are preserved due to the cold, fresh water,” said Magee. “Wrecks in salt water start corroding immediately. In the Great Lakes, you can find old wooden ships that are hundreds of years old that look like they just sank.”

One recent addition to the lake is obvious in the photos. Invasive zebra and quagga mussels, which arrived in the Great Lakes in the 1980s, cover most surfaces of the wreck. While the mussels have disrupted many aspects of Great Lake ecosystems, their population explosion in recent decades has had pros and cons for shipwreck divers.

“They’re filter feeders, so they’ve actually increased the clarity of the water. In many areas, the water is now so clear that we now can get bright, ambient light 200 feet below the surface,” explained Magee. “The downside is that instead of seeing bare wood, original paint, or anything else we’re trying to look at, we just see surfaces covered by lumps of mussels.”

NASA image by Alan Holmes/NASA's Ocean Color Web, using data from SeaHawk/HawkEye. Photographs courtesy of David VanZandt (Cleveland Underwater Explorers). Story by Adam Voiland.