In 1977, Mexico’s first shrimp farm was built in Sinaloa. Four decades later, the coastal state is one of the largest shrimp farming regions in Mexico, producing about 60 percent of the country’s harvest. As shrimp farms have grown, areas of coastal wetlands have been replaced by flooded land suitable for aquaculture. The transformation is extensive enough to be detected from space.

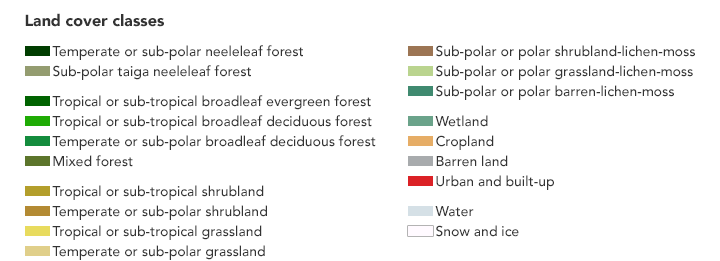

Changes along Sinaloa’s coast are visible in these maps, derived from the North American Land Change Monitoring System (NALCMS), a continent-wide mapping initiative supported by the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC). Released every few years, the maps display land cover types—wetlands, forest, farmland, etc.—and how they have changed across the continent. Maps of the U.S. and Canada are derived from Landsat satellite images; maps of Mexico also use RapidEye imagery.

The detailed views above show the coast of northwestern Mexico in 2010 (left) and 2015 (right). This northern part of the Sinaloa coastline, where it meets the Gulf of California, is rich with coastal wetlands along its bays and estuaries. Notice that vast areas of wetland (blue-green) and grassland (yellow) found along the coast in 2010 were inundated with water (light blue) by 2015.

Some of the change is due to natural shifts in the wetlands and the flow of water. Other changes reflect a human influence. Shrimp farms, for example, stand out as rectangular blue shapes.

According to Rainer Ressl of the National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity (CONABIO), the land use change due to shrimp farming spiked about 10 to 15 years ago amid globally low prices and high demand. “There has been significant reduction of mangroves due to aquaculture in Mexico,” he said.

Potential environmental impacts of shrimp farming go beyond the degradation and loss of mangroves. They can also alter the region’s natural flow of water and lead to the deterioration of water quality. Data like those in the maps above can inform land management and aquaculture practices, to help increase the sustainability of what has become an extremely important economic activity for the region.

The data are being made available to a wider audience via story maps and the Atlas of Nature and Society. “We have a lot of geospatial information, but not all is accessible in an easy way for non-experts,” said Ressl, whose team at CONABIO is one of the institutions responsible for the Mexican component of the NALCMS initiative. “What we are trying to do with this type of data visualization is to raise awareness in the general public of the main drivers of change of land cover in Mexico.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using data from the North American Land Change Monitoring System, an international initiative supported by the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC). U.S. Geological Survey partners include: Canada Centre for Mapping and Earth Observation (CCMEO, Natural Resources Canada); National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity (CONABIO); National Forestry Commission of Mexico (CONAFOR); and the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). Story by Kathryn Hansen.