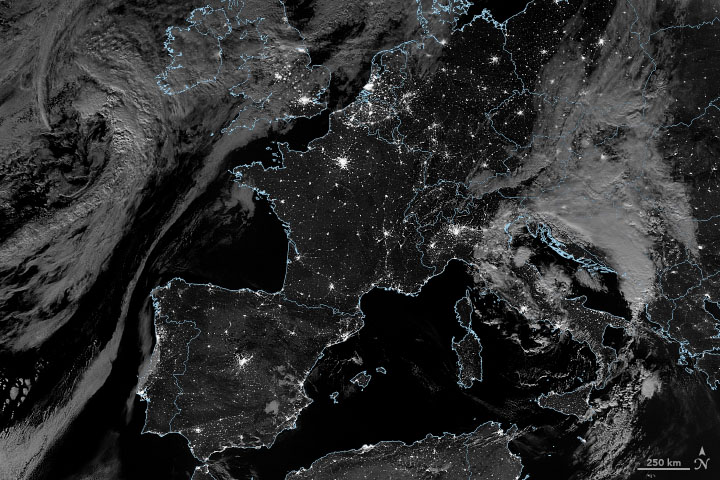

In the early morning hours of August 5, 2020, the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the NOAA-NASA Suomi NPP satellite got a clear view of Western Europe and its lights. The landscape was also well lit by the Moon, which was just one day past full. The following day was also mostly clear, as observed in the early afternoon by NASA’s Aqua satellite.

The image was acquired through the use of the VIIRS day-night band (DNB), which detects light in a range of wavelengths from green to near-infrared and uses filtering techniques to observe signals such as city lights, wildfires, airglow, and reflected moonlight. Since the launch of Suomi NPP in late 2011, scientists have been using VIIRS to provide unprecedented views of Earth at night. (See our gallery here).

Suomi NPP passes over any given location on Earth at roughly 1:30 a.m. and 1:30 p.m. local time each day, observing the planet in vertical strips from pole to pole. VIIRS is a spectroradiometer, detecting photons of light in 22 different wavelengths. The instrument produces an image by repeatedly scanning a scene and resolving it as millions of individual picture elements, or pixels.

The day-night band takes it a step further, determining whether to use its low, medium, or high-gain mode to ensure that each pixel accurately depicts the amount of light emitted. It can make quantitative measurements of light emissions and reflections, distinguishing the intensity and the sources of night light down to the scale of an isolated highway lamp or fishing boat. The sum of these measurements gives us a global view of the human footprint on Earth.

By mid-2000, at least 500 peer-reviewed journal papers have been published based on day-night band data, with another 120 combining DNB data with the older Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) observations. Subject areas have included social science (often demography and economics), atmospheric composition, civil engineering, biology, and natural resource monitoring and management.

“Nighttime imagery provides an intuitively graspable view of our planet,” said William Stefanov, a remote sensing scientist for the International Space Station science office. “City lights provide a fairly straightforward means to map urban versus rural areas, and to show where the major population centers are and where they are not. They are also an excellent means to track urban and suburban growth, which feeds into planning for energy use and urban hazards, for studying urban heat islands, and for initializing climate models.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using VIIRS day-night band data from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership. Story by Michael Carlowicz.