Pyrocumulonimbus. Fire clouds. Flammagenitus. Fire-breathing dragon of clouds. There are several terms for the towering clouds that occasionally rise above the smoke plumes of wildfires and volcanic eruptions. After several fire-triggered clouds sprang up in quick succession on January 4, 2020, and December 29, 2019, Australians have been getting familiar with all of those names.

Victoria and New South Wales are in the midst of one of the most severe fire seasons either state has seen in decades. After months of unusually hot, dry weather, hundreds of fires have charred an area larger than West Virginia, destroying thousands of homes and resulting in dozens of deaths.

The formation of pyrocumulus clouds requires fires to burn hot enough to create an updraft of superheated, fast-rising air. As the hot air rises and spreads out, it cools, causing water vapor to condense and form clouds. In certain conditions, powerful updrafts can create clouds that rise several kilometers and turn into full-fledged thunderstorms as they reach the top of the troposphere—turning a pyrocumulus into a pyrocumulonimbus. The storms pose serious risks for pilots and firefighters due to powerful turbulence.

Pyrcocumulus and pyrocumulonimbus clouds are fairly common. Scientists at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), NASA, and several other institutions track dozens of them each year. But the sheer number and intensity of the recent fire clouds in Australia has many scientists saying this event may be one for the record books.

Meteorologist Michael Fromm and colleagues at NRL counted more than 20 firestorms in the last week of December 2019 and the first week of 2020. “By our measures, this is the most extreme pyrocumulonimbus storm outbreak in Australia,” Fromm said. And with extreme weather conditions forecasted in the coming days, it's likely there are more to come.

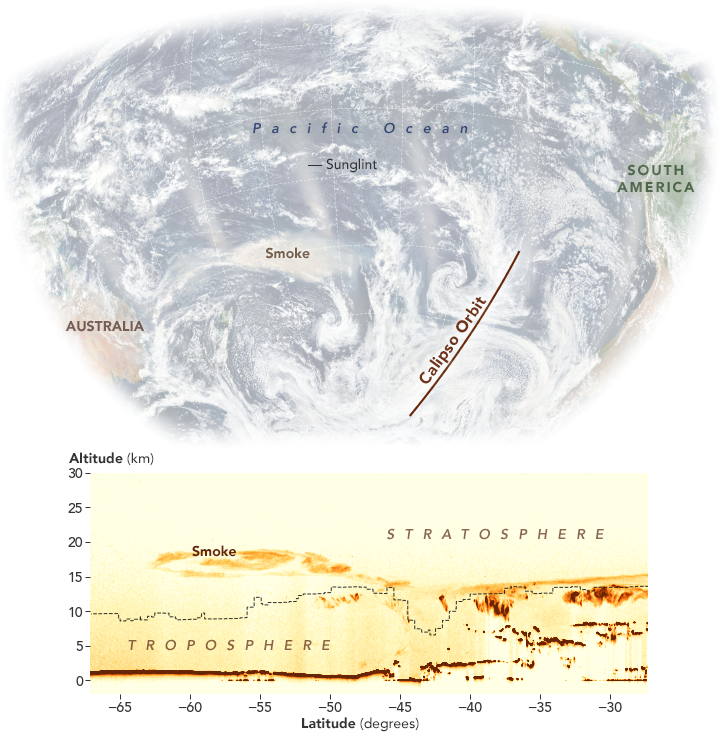

The fire clouds have lofted smoke to unusual heights in the atmosphere. The CALIPSO satellite observed smoke soaring between 15 to 19 kilometers (9 to 12 miles) on January 6, 2020—high enough to reach the stratosphere.

“It is premature to compare and rank the height of this plume with others because smoke plumes like this rise in altitude over the course of weeks,” said Fromm. “That said, preliminary evidence indicates that the current Australian event will probably fall within the top five of all the plumes ever documented in terms of height. And the overall volume of smoke injected into the stratosphere appears to be among the largest observed in recent decades.”

The January 6 natural-color image (above) comes from the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the Suomi NPP satellite. The data in the transect reveals the height of dust and smoke as observed by the Cloud-Aerosol Lidar with Orthogonal Polarization (CALIOP) instrument on the CALIPSO satellite. While the visualization shows long, thin plumes of smoke stretching across the Pacific Ocean, the clouds (small, shaded areas) detected were all lower than 14 kilometers (8 miles). In the natural-color image, sunglint caused by the reflection of light left bright areas at regular intervals. The photograph below from the International Space Station shows extreme fire activity on January 4, 2020.

When volcanic plumes reach the stratosphere, they are closely watched by scientists because they can cause widespread atmospheric cooling in the months after the eruption. Wildfire smoke has a different composition—more sooty black carbon than sulfates, for instance—so the consequences for weather and climate are not as well understood. Smoke this high in the atmosphere also may have effects on the chemistry of stratospheric ozone.

Smoke that reaches the stratosphere generally stays there for several months, traveling thousands of kilometers from its source. Since the recent outburst of fire clouds, many different satellite sensors have collected images of vast plumes crossing the Pacific.

“NASA is currently tracking the movement of smoke from the Australian fires using several sensors,” said Colin Seftor, a scientist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. “The smoke had a dramatic impact on New Zealand, causing severe air quality issues across the county and visibly darkening mountaintop snow. Beyond New Zealand, the smoke has now travelled more than halfway around the Earth, crossing South America, turning the skies hazy, and causing colorful sunrises and sunsets. It is expected to make at least one full circuit, returning once again to the skies over Australia.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using data from the CALIPSO team, and VIIRS data from NASA EOSDIS/LANCE and GIBS/Worldview and the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership. Story by Adam Voiland.