After traveling more than 30,000 miles in six years, J. Dewey Soper’s ultimate quest was finally coming to an end. The Canadian explorer had been commissioned in 1923 to explore the country’s northernmost regions to collect plant, animal, and geological specimens, many of which sit in Canadian museums today. Venturing into the harsh conditions of the Arctic with the help of the Inuit people, he surveyed the land, created maps, and made scientific observations to better understand the country’s far north.

But Soper was still missing what he called “one of the leading enigmas in North American ornithology”—the exact location of blue geese breeding grounds. The mystery was of personal interest to the ornithologist, who from a young age was obsessed with learning about native birds and mammals. For centuries, no explorer or researcher had been able to document the North American bird’s nesting grounds.

In 1928, Soper finally received information that would help solve the mystery. A Nuwata Inuk man known as Salia said he knew where the blue geese nested and drew Soper a map of an area along the Foxe Basin coast, north of Bowman Bay. Using Salia’s map, Soper and a group of five Inuit—traveling on sledges pulled by 42 sled dogs—embarked on the search in May 1928. On June 2, a single flock of mixed snow geese and blue geese flew over their camp near Bowman Bay. Four days later, thousands of honking birds flew overhead. They had found the nesting site.

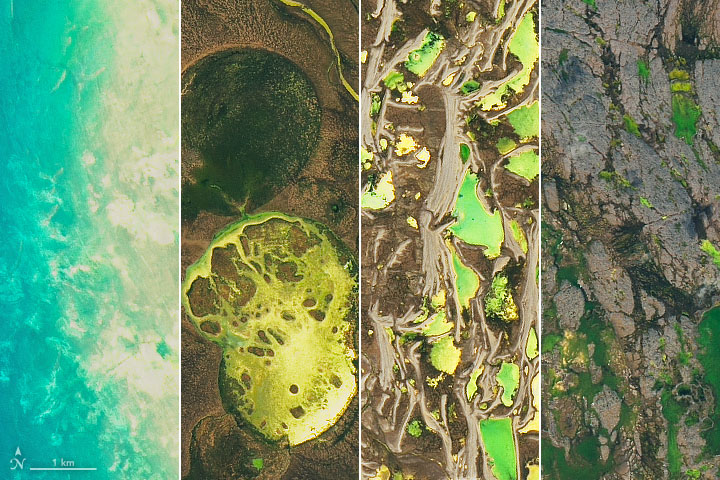

The site on the southern coast of Baffin Island (in modern Nunavut territory) is visible in the top image, acquired on September 14, 2019, by the Operational Land Imager on Landsat 8. Established in 1957, the Dewey Soper (Isulijarnik) Bird Sanctuary was the first sanctuary created in the Arctic.

Soper studied the geese on Baffin Island and confirmed that the blue geese and snow geese are the same species, but just different colors—similar to how humans have different colored hair. Researchers have since found that a single gene controls the color difference.

Nearly one million snow geese nest in or around the sanctuary—about one-third of all the snow geese in the world—making it the largest known snow goose colony. The snow geese arrive in late May and depart around mid-September. The area is also an ideal habitat for large populations of Sabine’s gulls, cackling geese, Atlantic brant, and long-tailed ducks and eiders.

The sanctuary supports a wide variety of life due to its diverse terrain. The image above is a mosaic of various landscapes found in and around the sanctuary, which is part of the Great Plain of the Koukdjuak. Moving inland from the coast, the land increases in elevation and decreases in soil moisture. The coast (left) is marshier, muddier, and wetter, with meadow-type habitats. Atlantic brant and Ross’s geese are found on these damp plains. The second and third images show circular, shallow lakes and small streams that drain the marshy plain. Further inland, the drier, higher elevation areas contain more gravel and plants suited to the dry conditions, such as wintergreen and mountain cranberry. The right image shows the southern part of the plain, which has much rougher and rockier terrain.

According to Soper, the investigation of the breeding site is one of the most outstanding achievements of his expeditions. Soper credits his Inuit guides stating, “My Eskimo informers were proved right and I blessed them for it.”

Also an artist, Soper documented his journey in watercolor—from the geese he observed to his surrounding landscape and community. Figuratively and literally, he helped paint a better understanding of Canada’s northernmost region.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Kasha Patel.