August 1, 2019

There is no award for completing the walk from Mexico to Canada through California, Oregon, and Washington. But read about the journeys of so-called “thru-hikers” of the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT), and it is clear that the 2,650-mile (4,265-kilometer) hike changes you. Even walking a small segment of trail can connect you with the land, whether you access the PCT in desert, forest, or alpine areas.

In 2018, the U.S. National Trails System celebrated its 50th anniversary. Of the eleven National Scenic Trails that exist today, only two—the PCT in the West and the Appalachian Trail in the East—have been around since the beginning. Decades of planning, scouting, and building culminated in a “completion” ceremony for the PCT in 1993, although protection of existing trails and acquisition of new ones on private lands are ongoing.

A group of hikers make their way through Three Sisters Wilderness, Oregon. (Photo: Eric Sanman.)

The PCT is not the longest National Scenic Trail—that designation goes to the North Country Trail—but it set the stage for trails that followed. The remarkable length of the Pacific Crest Trail, passing through 48 wilderness areas and some extremely demanding terrain, is especially apparent from space.

NASA Earth Observatory identified locations along the trail where satellites and astronaut photography offer a unique perspective. Most thru-hikers walk the trail from south to north over the span of many months starting around mid-April to early May. This direction and timing align with favorable desert temperatures in the south and seasonal snowmelt on the trail.

Lush vegetation and stunning views greet PCT hikers in Washington state. For 500 miles, the trail climbs mountain passes, dips into valleys, winds around volcanoes, and shoots across miles of meadows. The Pacific Crest Trail Association calls the segment through Washington a “highlight of the trail.” Just prepare to get wet; storms can pop up any time, particularly in the North Cascades.

Almost nine miles of trail extend into Canada, but it’s not legal to enter the United States via the PCT. Most southbound hikers chose an access point in the United States, such as Hart’s Pass, then hike to the trail’s official northern terminus on the U.S.-Canadian border near Manning Park.

Terminus

Mileage: 0 southbound (2,650 northbound). Monument 78, located on the U.S-Canadian border, is considered the start (or end) of the trail.

Lakeview Ridge

Just eight miles from the U.S.-Canadian border, hikers encounter the highest point of the Washington segment of the PCT at an elevation of 7,126 feet (2,172 meters).

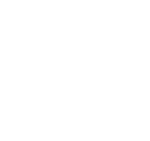

The North Cascades

This remote, wild, and often wet part of the trail contains hundreds of snowfields and small glaciers that persist year-round

California’s High Sierra often come to mind when hikers think of the PCT’s most rugged areas. But the North Cascades are similarly rugged: Hikers walk a roller-coaster of trails up passes and down into canyons: climb, descend, repeat. The area is also very remote, passing through multiple wilderness areas. About 18 miles of the trail passes through North Cascades National Park. That mountainous, secluded landscape is visible in this image (below), acquired in June 2017 with the Operational Land Imager on Landsat 8.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and ASTER digital elevation model data (GDEM2) from NASA/METI/AIST/Japan Space Systems, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team.

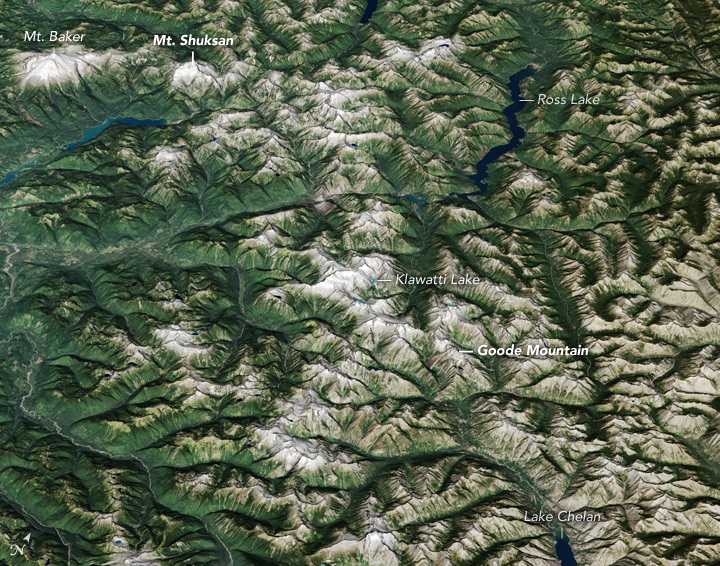

Snow is a huge consideration for hikers, especially those who start in Washington. Snow persists into late spring, and it adds risk to the many steep slopes and ridgelines. Adding to the challenge is that no two snow years are exactly alike. After several years of drought and low snowpack, mountain snow in 2017 was exceptional. These images, acquired by NASA’s Terra satellite, show the difference in northern Washington’s snow cover in May 2017 (a heavy snow year) and May 2005 (a light snow year).

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS/LANCE and GIBS/Worldview.

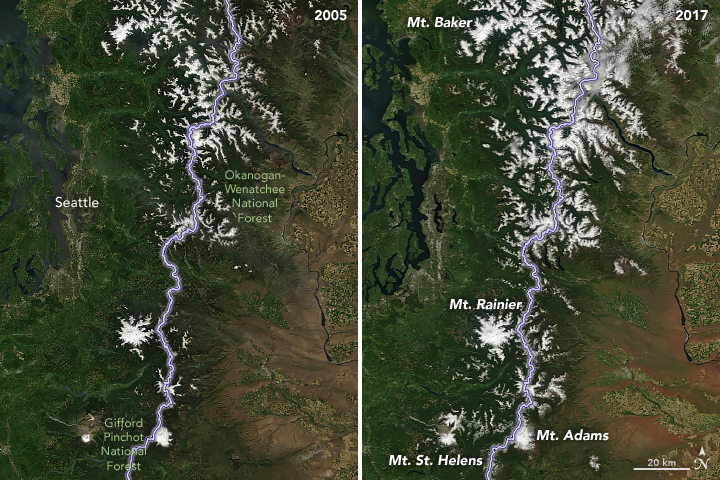

The PCT wraps around Washington’s most majestic peaks, including some notable volcanoes. Glacier Peak and Mount Adams show up along the route. And then there’s Mount Rainier. While this iconic Washington volcano does not fall precisely on the route, the views of the mountain from the PCT are worthy of a postcard. So too are the views from space. An astronaut on the International Space Station snapped this photograph of Mount Rainier in July 2018.

Astronaut photograph ISS056-E-85160 was acquired on July 8, 2018, and is provided by the ISS Crew Earth Observations Facility and the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, Johnson Space Center.

Hikers can neither start nor finish the PCT in Oregon, but this middle state can stand on its own in terms of beauty. Volcanoes of the Cascades continue to punctuate a landscape that is also dotted with lakes and old-growth forests. The Pacific Crest Trail Association calls the segment “relatively easy travel,” which is probably a welcome phrase to any thru-hiker.

Columbia River

The Bridge of the Gods spans the Columbia River and allows hikers to cross between Washington and Oregon. It also marks the trail’s lowest point, with an elevation just above sea level.

Mount Hood

Hikers are not required to summit Mount Hood, which at 11,239 feet (3,429 meters) above sea level is the state’s tallest peak. Instead, the trail meanders around the mountain’s southwestern flank.

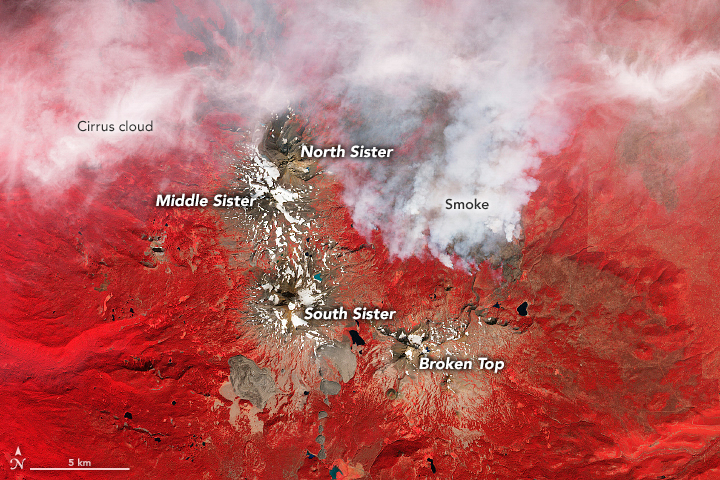

Three Sisters

About 40 miles of trail pass through the Three Sisters Wilderness area and include views of the North, Middle, and South Sister volcanoes. This bit of trail is a good place to witness the effects of glaciation on the landscape.

Crater Lake

Starting in the mid-1990s, an alternate trail opened that allowed hikers access to the lake. Six miles of trail follow the edge of the caldera before rejoining the PCT.

More than half of the federal land crossed by the Pacific Crest Trail is officially designated as wilderness. There is the occasional road crossing, however, such as the Bridge of the Gods.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and topographic data from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM).

By the time they reach northern Oregon, southbound and northbound hikers have passed plenty of volcanoes, but they’re not out of the Cascade Arc yet. This is where the trail crosses the flanks of Mt. Hood—the state’s tallest peak. This stratovolcano is shown here from the vantage point of an astronaut’s digital camera.

Astronaut photograph ISS036-E-23847 was acquired on July 24, 2013, and is provided by the ISS Crew Earth Observations Facility and the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, Johnson Space Center.

In September 2012, the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) on NASA’s Terra satellite acquired this false-color image of the Three Sisters and Broken Top volcanoes near Bend, Oregon. The smoke comes from the Pole Creek fire, which was burning east of the trail in the Three Sisters Wilderness. Officials temporarily closed part of the trail, and hikers had to follow a re-route option. At least some of the trail is closed a bit each year due to fire, although some years are worse than others.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, using data from NASA/METI/AIST/Japan Space Systems, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team.

Lakes abound along the PCT, but perhaps the most famous is Crater Lake in southwest Oregon. Measuring 1,943 feet (592 meters) deep, it is the deepest lake in the United States. An astronaut aboard the International Space Station shot this photograph in June 2017, when snow still blanketed most of the crater slopes.

Astronaut photograph ISS052-E-8744 was acquired on June 26, 2017, and is provided by the ISS Crew Earth Observations Facility and the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, Johnson Space Center.

Roller-coaster-like elevation changes return in California, as hikers maneuver the southern Cascades and the Sierra Nevada. In the north, your eyes can feast on the epic views of Mount Shasta and Mount Lassen. You then enter the High Sierra, home of the tallest mountain in the contiguous U.S. The terrain is demanding but beautiful, and draws plenty of day- and section-hikers.

Mount Shasta

The majestic mountain is at least partly visible from the trail for at least 500 miles.

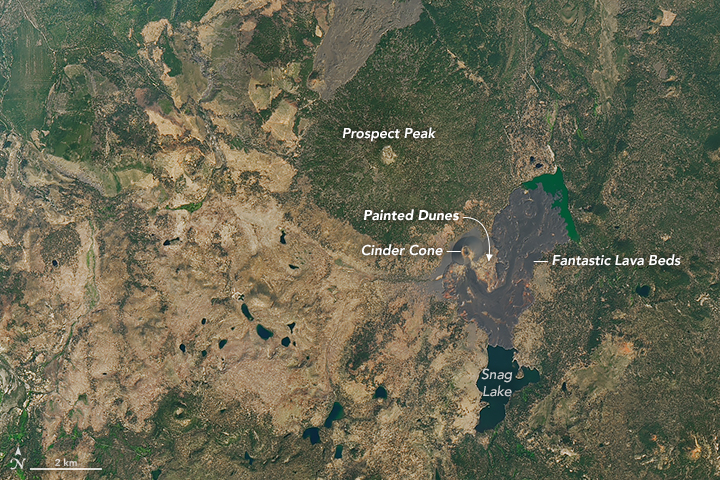

Lassen Volcanic National Park

A 17-mile-long stretch of trail runs through this park, with epic views of Mount Shasta and Mount Lassen.

Tahoe National Forest

This section of trail in the Northern Sierras features alpine lakes, meadows, conifer forests, and high alpine ridges.

Towering above the horizon at 14,179 feet (4,322 meters), Mount Shasta is sure to catch the eye of hikers along the PCT. But the volcano also plays an important role in catching water for the region. Seasonal snowpack replenishes the local water supply that feeds rivers, streams, and nearby Shasta Lake—the state’s largest reservoir.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens and Robert Simmon, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and topographic data from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM).

About 70 miles (110 kilometers) to the southeast of Mount Shasta, snowy peaks give way to the lava flows and pumice-covered dunes of Lassen Volcanic National Park. This stunning landscape has its origins in an eruption of ash and lava from Cinder Cone in the year 1666.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Although the PCT does not lead directly to the shores of Lake Tahoe, the clear, cool waters—fed by 63 streams—beckon weary hikers. The PCT meanders west of the iconic lake, passing through Granite Chief Wilderness and Desolation Wilderness areas. The majesty and diversity of the landscape is matched by that of the wildlife found here: mule deer, black bear, bobcat, pine marten, and the elusive wolverine.

Astronaut photograph ISS052-E-30463 was acquired on August 6, 2017, and is provided by the ISS Crew Earth Observations Facility and the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, Johnson Space Center.

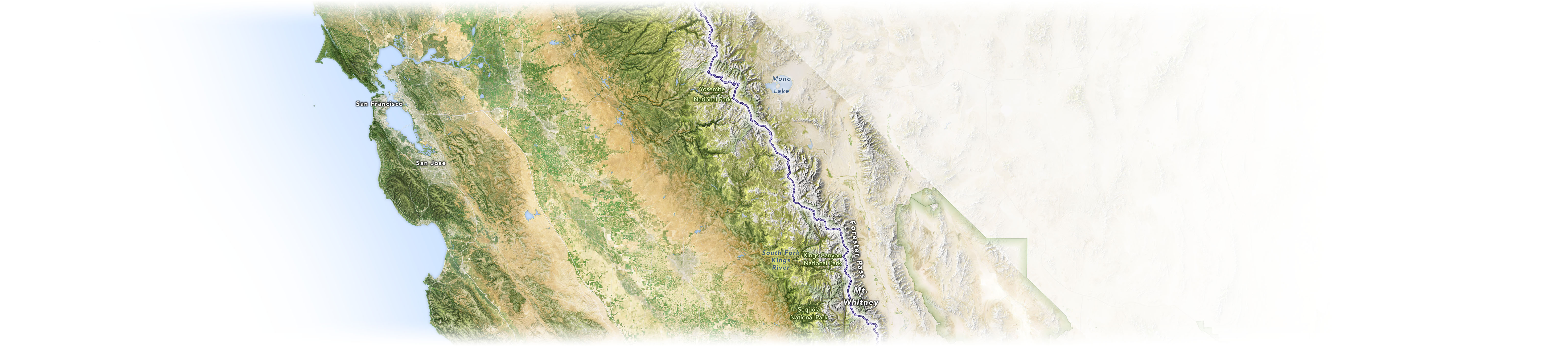

Both the John Muir Trail and the much longer PCT traverse Forester Pass, the highest point of either trail at 13,153 feet (4,009 meters). The pass straddles Sequoia National Park and Kings Canyon National Park. It is at the top of this divide that water drains northward to the Kings River or southward to the Kern River. From this point, hikers get views of rolling tundra in one direction and the Kaweah Peaks in the other.

Yosemite National Park

From this 75-mile (120-kilometer) segment of trail, hikers can access some of the park’s most notable wonders, such as Half Dome and Tuolumne Meadows.

Kings Canyon National Park

Some of the largest trees in the world grow in the southern Sierra Nevada.

Mount Whitney

At 14,505 feet (4,421 meters) above sea level, it is the tallest mountain in the contiguous U.S.

Forester Pass is shown below in a map made from natural-color imagery from NASA’s MODIS Blue Marble, draped over an elevation model from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using MODIS/Blue Marble Next Generation data and topographic data from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM).

River crossings along the trail can be treacherous at any time, but years with heavy snowfall and rapid melt are particularly dangerous. That was the case in 2017, when a heatwave in mid-June quickly melted the winter snow and caused flooding. These images show the crossing at South Fork on the Kings River in July 2016 and 2017.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Hikers don’t need to climb Mount Whitney to complete the PCT. Still, many hikers make the detour from the main trail to summit this mountain. Climbing the tallest mountain in the Sierra Nevada means facing low oxygen levels; this can be a problem for hikers coming from sea level, though PCT thru-hikers are probably well acclimated by this point. This image shows the Sierra Nevada and Mount Whitney from the east, as seen by an astronaut aboard the International Space Station.

Astronaut photograph ISS050-E-17326 was acquired on December 19, 2016, and is provided by the ISS Crew Earth Observations Facility and the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, Johnson Space Center.

The last (or first) 700 miles of the PCT are “easily accessible,” according to the Pacific Crest Trail Association. Indeed, trail access is a manageable drive from major Southern California cities, such as Los Angeles and San Diego. Southbound hikers exiting the Sierra Nevada get to experience the desert. Depending on the time of year, these areas can be notoriously hot and dry. But you also get to witness the plants and animals unique to the environment.

Cameron Ridge

Get a close-up look at enormous wind turbines along this short, 6.5 mile (10 kilometer) stretch of trail.

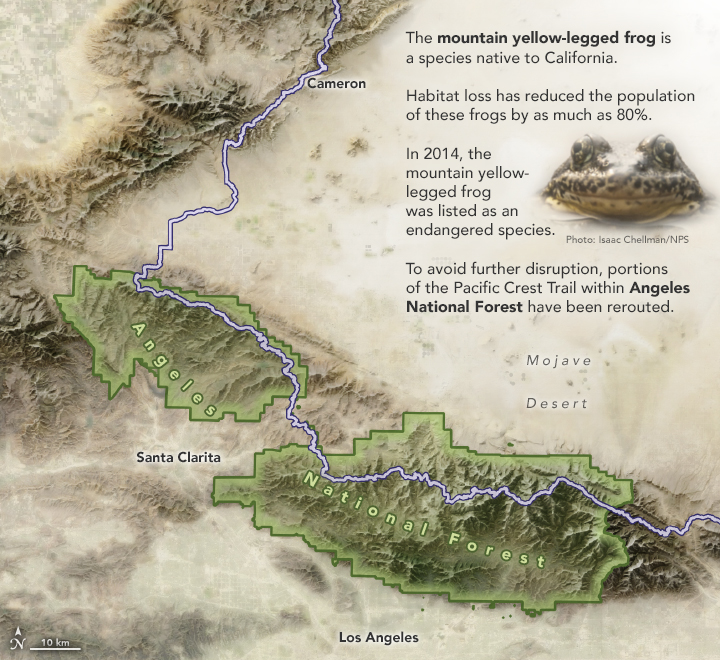

Angeles National Forest

Relatively close to Los Angeles, this forest is accessible to day-hikers. It is also extremely dry and prone to fires.

Southern Terminus

Mileage: 2,650 southbound (0 northbound). The end (or start) of the PCT is located about a mile from Campo, California, near the U.S.-Mexico border.

From a distance, rows of windmills lined up in the desert seem to be silently performing their wind-to-energy duties. Encounter them up-close, however, and you can hear their striking “whoosh-whoosh” sound. For a short distance, the PCT takes hikers right up to some of these turbines. Day-hikers can also easily access this unusual part of the trail.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Fire and snow are common reasons for hikers to detour from the standard PCT route. Animals can also affect the journey. In the Angeles National Forest, a permanent detour was recently created in order to avoid the habitat of an endangered species of frog.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using MODIS/Blue Marble Next Generation data and topographic data from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM).

Atop a small hill at an elevation of 2,915 feet (888 meters), just south of Campo, California, southbound hikers complete their 2650-mile-long journey. Northbound hikers, conversely, might still have stiff soles and soft feet.