“PACE is a mission that will use the unique vantage point of space to study some of the smallest things that can have the biggest impact.” — Karen St. Germain, director of NASA’s Earth Science Division

The skies above us are teeming with tiny particles of dust, sea salt, smoke, and human-made pollutants. The seas, oceans, and lakes around us are teeming with microscopic, plant-like organisms. In both cases, individual bits of these tiny living and inanimate particles are too small for your eye to see. But when billions to trillions of them aggregate in one place, we can see them from space. And these little things make a vast difference for life on Earth.

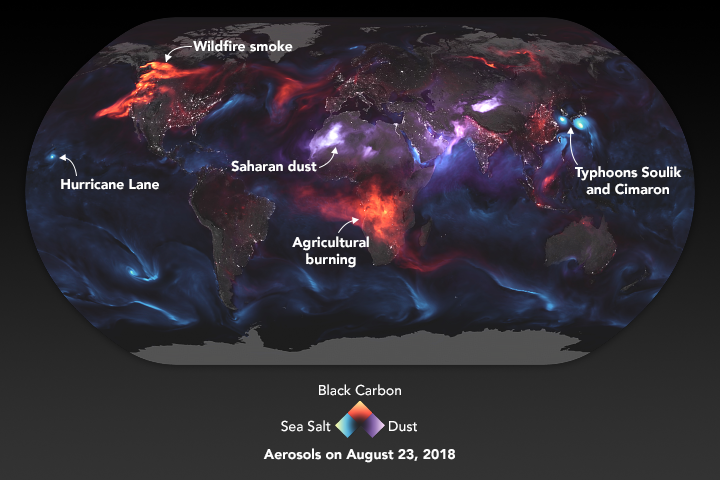

The particles in the air are known to atmospheric scientists as aerosols. Though the spray cans you might use for paint or hairspray do contain aerosols, the ones PACE will study are the flecks of carbon that rise from wildfires and smokestacks; the fine, dusty minerals that get lofted from deserts into the sky by strong winds; the nitrates and sulfates spewed by cars, trucks, and ships in their exhaust; and the salty spray from crashing waves and strong winds blowing over the ocean.

Why study them? Because those particles influence air quality, sometimes making it unhealthy to breathe, especially if you have asthma or heart and lung conditions. Pollution and smoke don’t observe borders – we all share Earth’s air — so it’s important to know something about the sources and types of particles floating around us. On the positive side, the bits of mineral dust or smoky aerosols can sometimes fertilize the ocean, providing nutrients for phytoplankton to bloom.

Aerosols also affect weather and climate. Tiny particles in the air reflect sunlight, and how much they reflect affects how much the land and ocean surfaces heat up. Aerosols also “seed” the formation of clouds: they provide surfaces on which water droplets form (condensation nucleii) as they aggregate into clouds. One of the great unknowns in our models of climate change is what role will aerosols will play in changing rainfall and snowfall patterns and in the heating or cooling of our atmosphere.

Though NASA has been studying aerosols from space for decades — observing where they are and the abundance of them — PACE and its SPEXone and HARP2 polarimeters will change the game. The instruments will tell us the shape and size of aerosols, helping us answer questions about where they come from and how they might influence other parts of the Earth system.

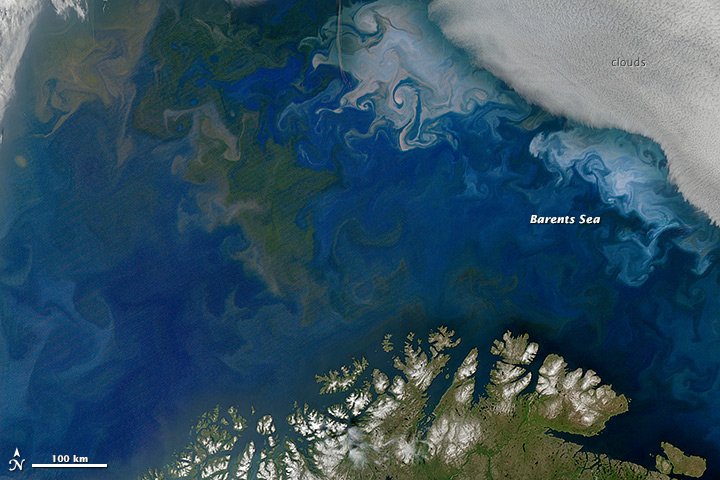

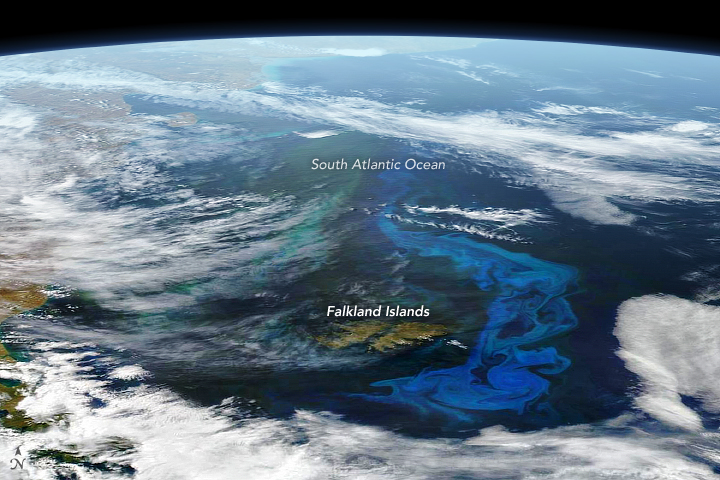

The other little things that PACE will examine have names like diatoms, coccolithophores, cyanobacteria, algae, and dinoflagellates. To borrow and mangle a quote from one of my favorite movie characters — Annie Savoy in Bull Durham — if you have three phytoplankton, they can’t do much. But if you have 300 billion of them, they can build a cathedral. Well, maybe not a cathedral, but they can develop into vast blooms that have a profound impact on life on this ocean planet.

Phytoplankton grow constantly on Earth and just about anywhere there are open, sunlit patches of water. When conditions are right, the growth of these microscopic cells can blossom to scales that are visible from orbit for days to weeks.

Phytoplankton are to the ocean what grasses and ground cover are to land: primary producers, a basic food source for other life, and the main carbon recycler for the marine environment. They are floating, plant-like organisms that soak up sunshine, sponge up nutrients, and create their own food (energy).

Why do we need to study these tiny organisms with PACE? While humans don’t really consume phytoplankton for food, the little floaters are fuel for the zooplankton, fish, and shellfish that we do eat. We also need to care about phytoplankton because they can influence water quality and human health. Some species of phytoplankton produce toxins that are dangerous to humans and animals; others can grow in such abundance that they crowd out other species or deplete the water of necessary oxygen.

Speaking of oxygen, phytoplankton produce a lot of it. Somewhere between 20 and 50 percent of the oxygen on Earth — some in our air, a lot in the ocean — is made by phytoplankton as they use photosynthesis to turn sunlight, carbon dioxide, and nutrients into sugars. In the process, they also draw carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and, in time, sink it to the bottom of the ocean.

Better understanding the phytoplankton in the ocean will help us better understand the fisheries that feed us and our economy, and it can ultimately help us work toward cleaner waterways.

NASA and its research partners have been studying phytoplankton from space for decades, but mostly with just a few wavelengths of light. I am looking forward to the colors, textures, and details we will see with PACE’s OCI hyperspectral imager. As the PACE science team likes to say: we have been coloring the ocean with a box of 8 crayons, and now we are about to get a box with 128 shades of color. The leap in detail will allow scientists to better spot where phytoplankton are, but also figure out who (what species) they are.

And when PACE data are combined with observations from our recently launched SWOT mission — which studies the shape and movement of the surface of the ocean — it will be like going from the Earth-observing equivalent of the Hubble Space Telescope to the new James Webb Space Telescope.

Learn more about phytoplankton with these resources:

PACE Phytoplankton Exploration

The Insanely Important World of Phytoplankton

NASA Wants to Identify Phytoplankton Species from Space: Here’s Why.

As the Seasons Change, Will the Plankton?

Phytoplankton May Be Abundant Under Antarctic Sea Ice

Learn more about aerosols with these resources:

Just Another Day on Aerosol Earth

New NASA Satellite to Unravel Mysteries About Clouds, Aerosols

Global Transport of Smoke from Australian Bushfires