At the base of the ocean food web are single-celled algae and other plant-like organisms known as phytoplankton. Like plants on land, phytoplankton use chlorophyll and other light-harvesting pigments to carry out photosynthesis, absorbing atmospheric carbon dioxide to produce sugars for fuel. Chlorophyll in the water changes the way it reflects and absorbs sunlight, allowing scientists to map the amount and location of phytoplankton. These measurements give scientists valuable insights into the health of the ocean environment, and help scientists study the ocean carbon cycle.

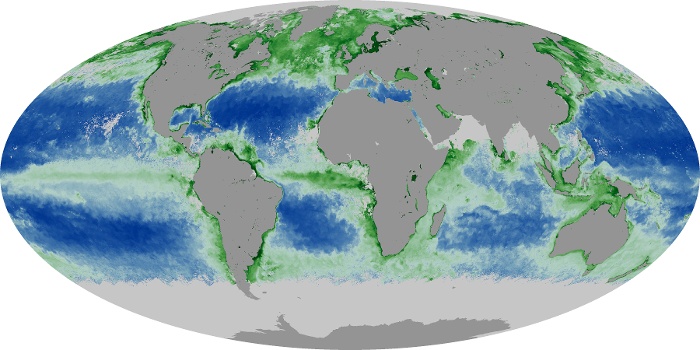

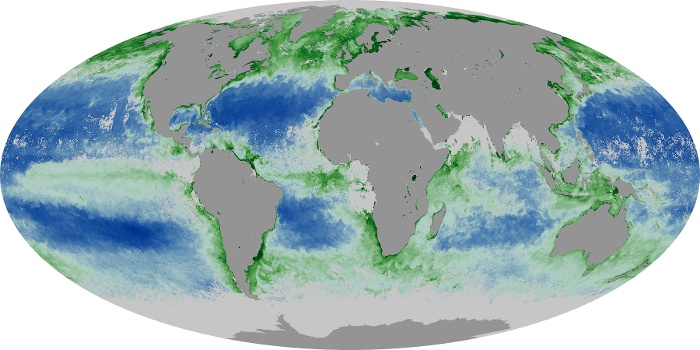

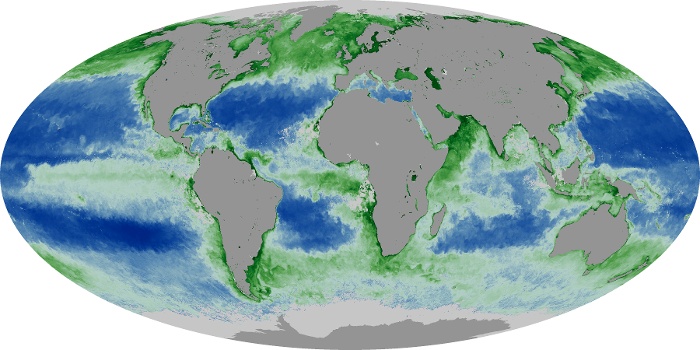

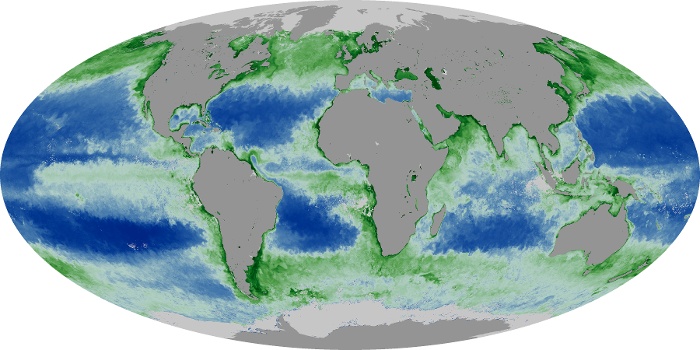

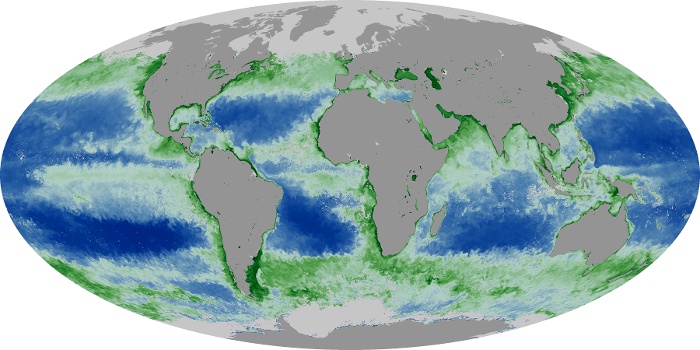

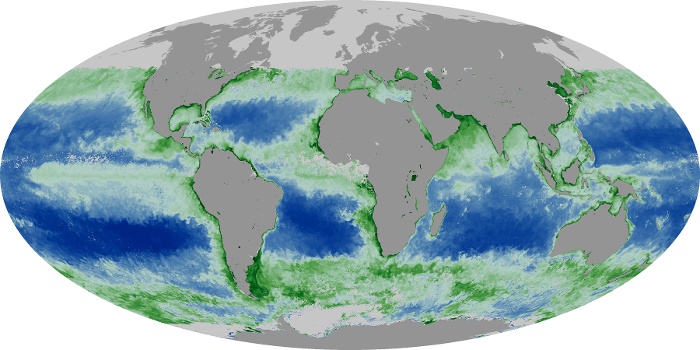

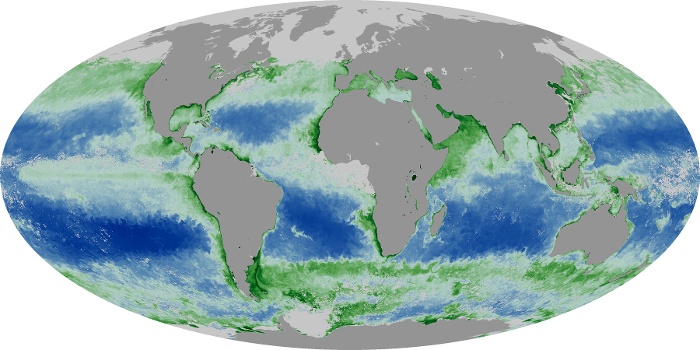

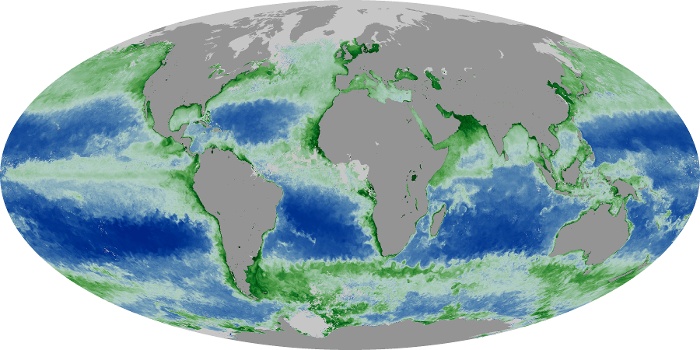

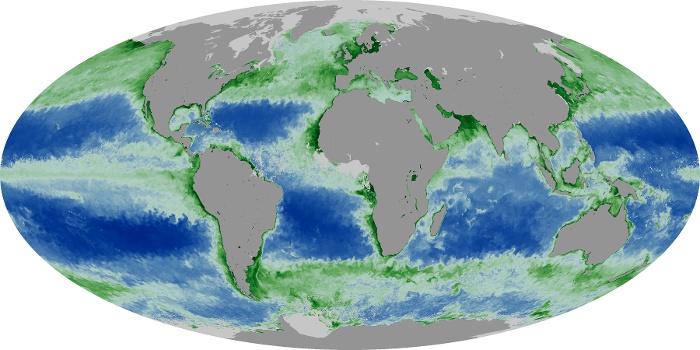

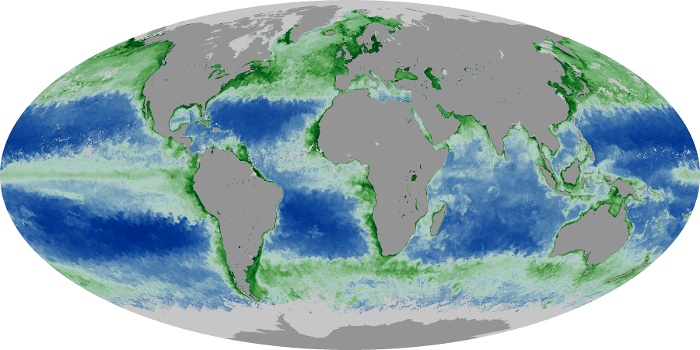

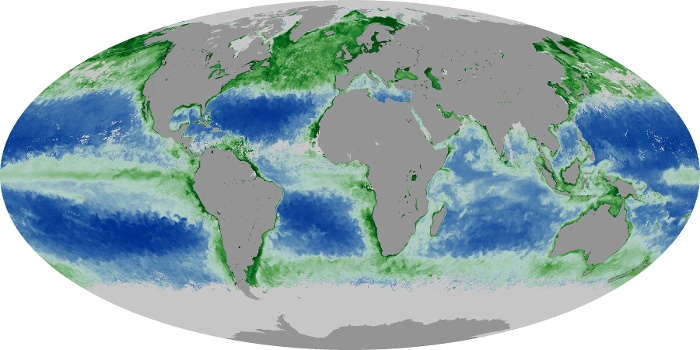

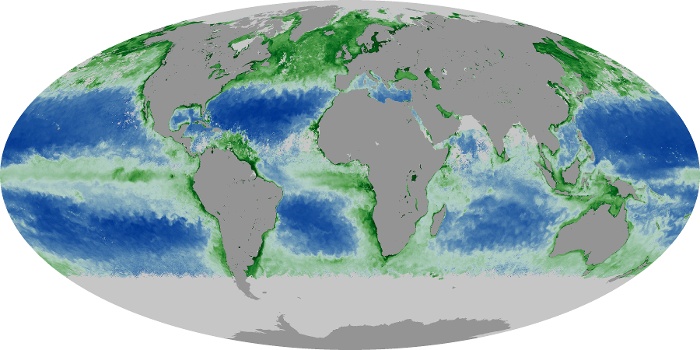

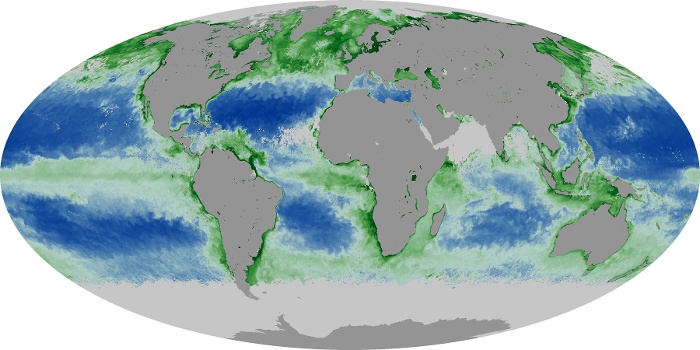

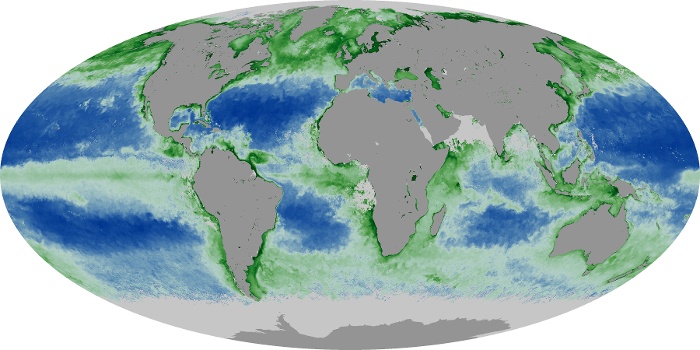

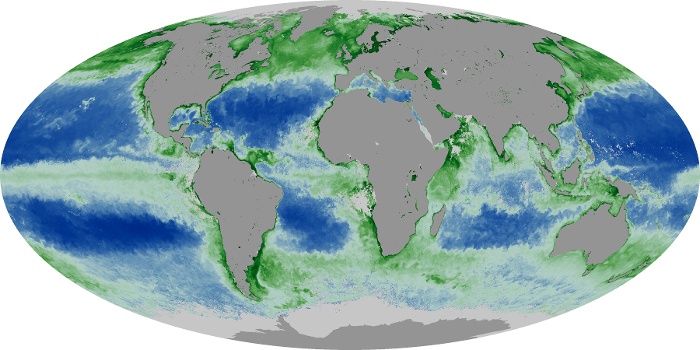

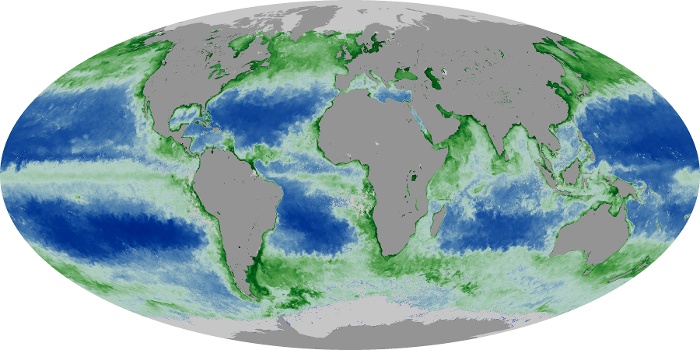

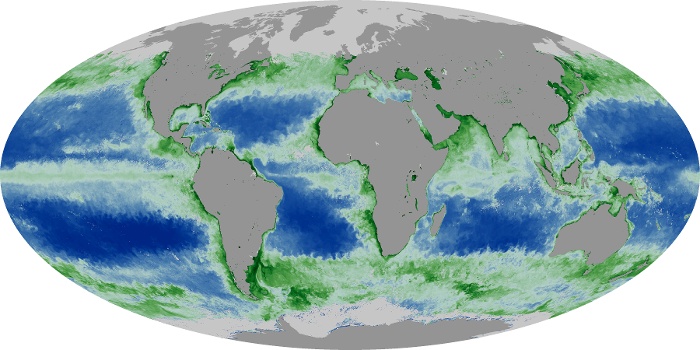

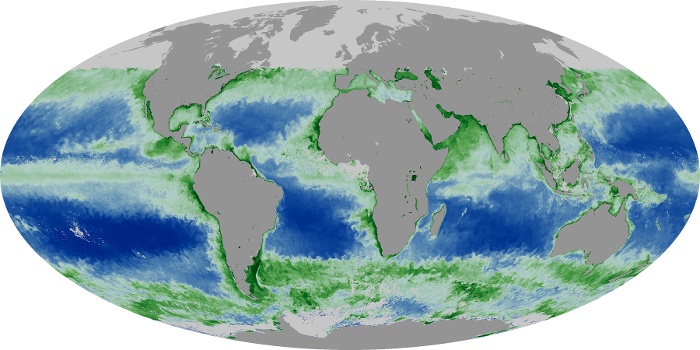

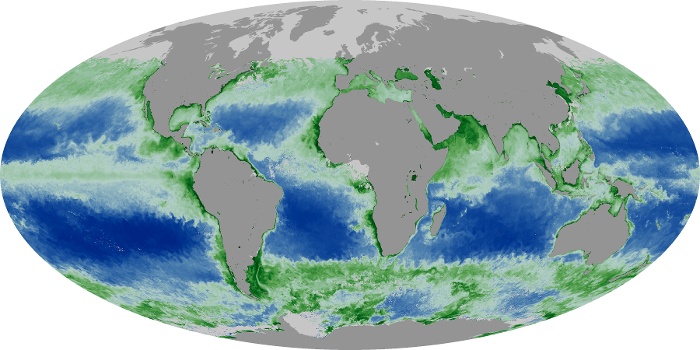

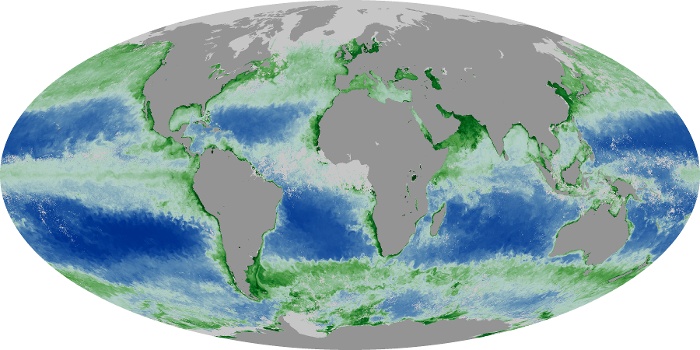

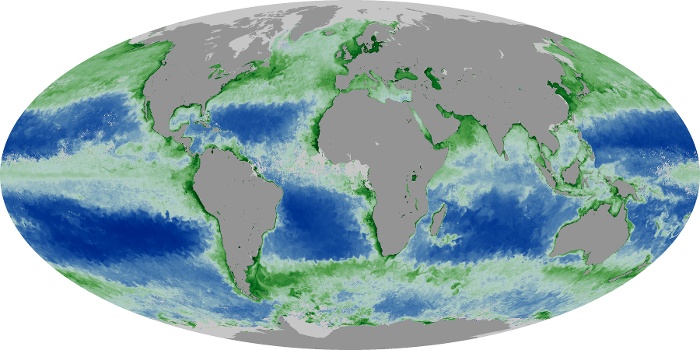

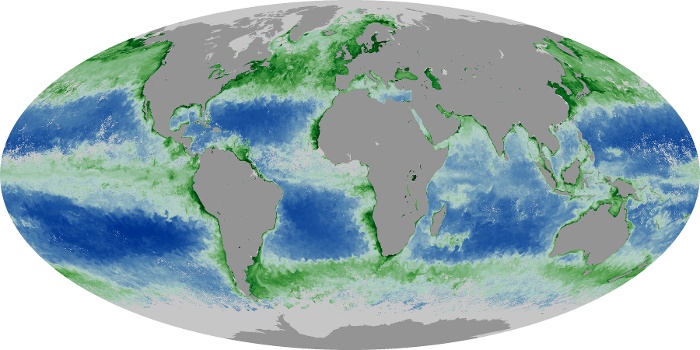

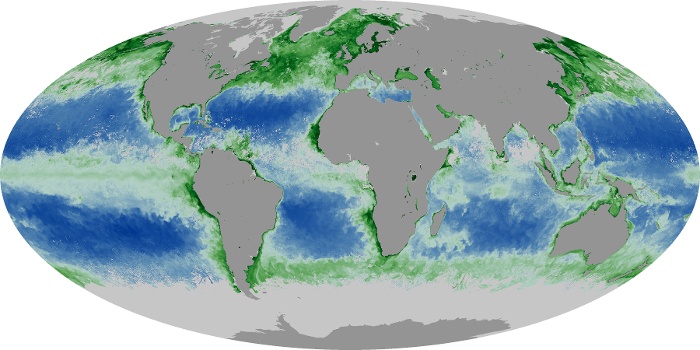

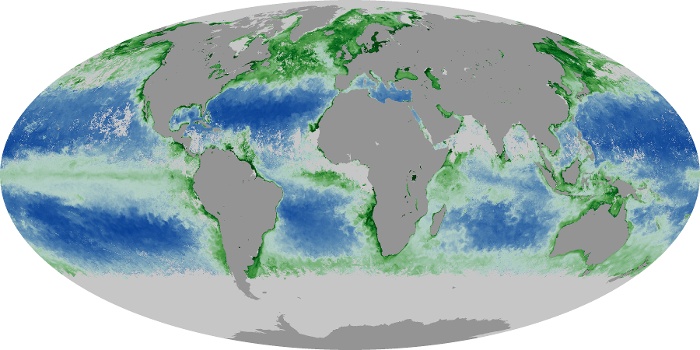

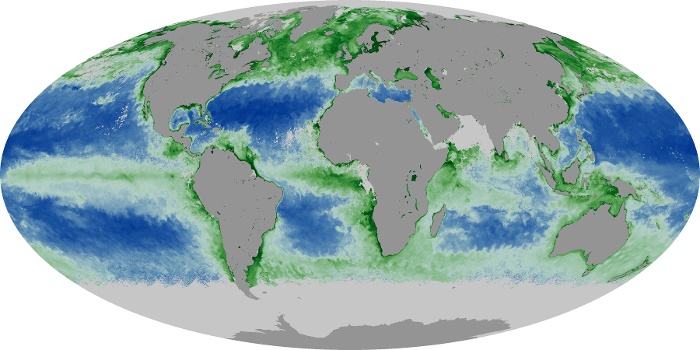

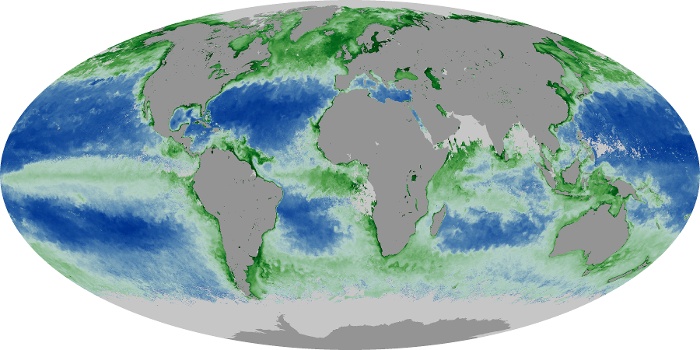

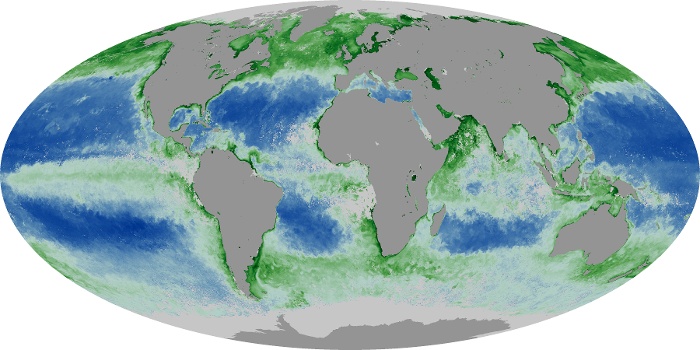

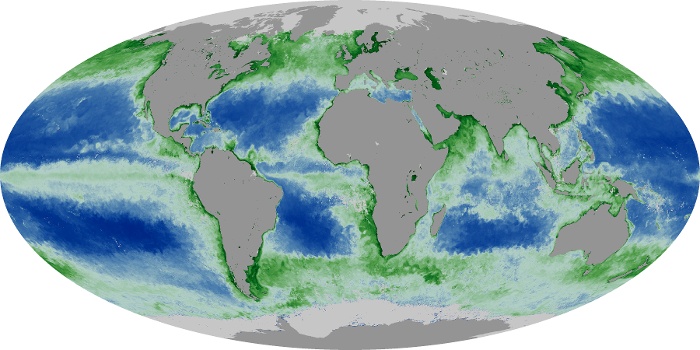

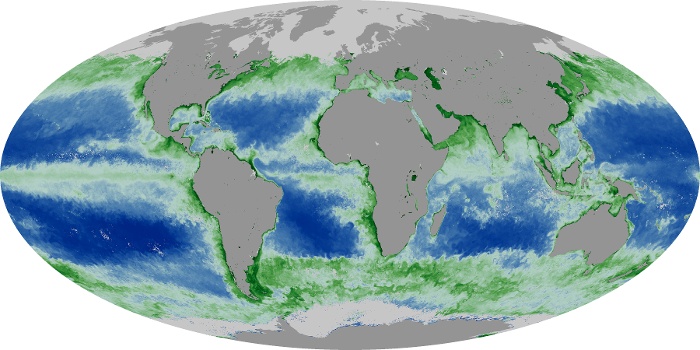

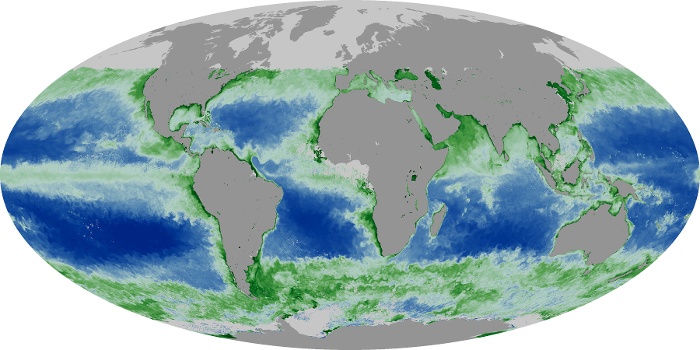

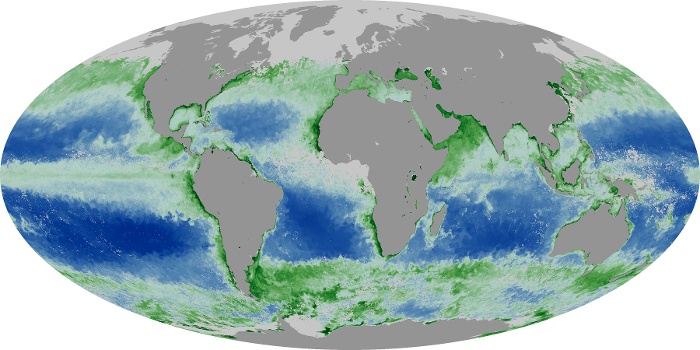

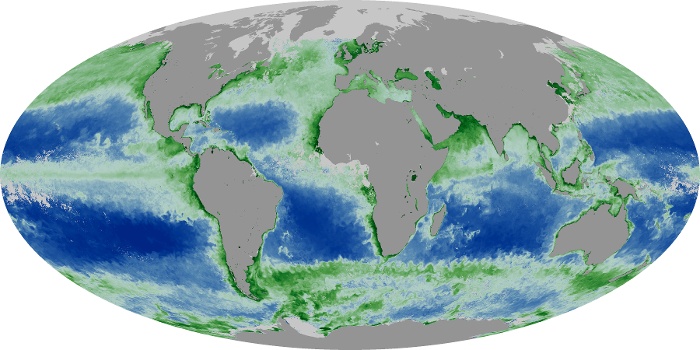

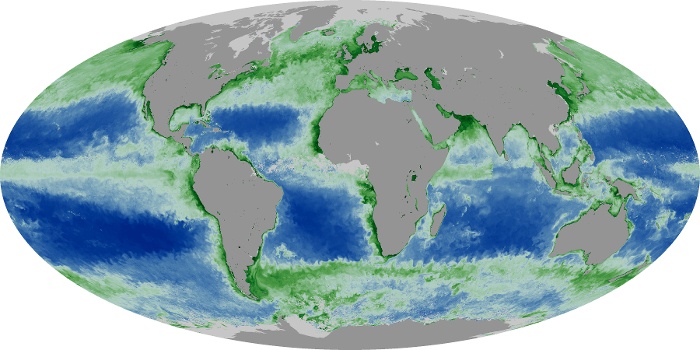

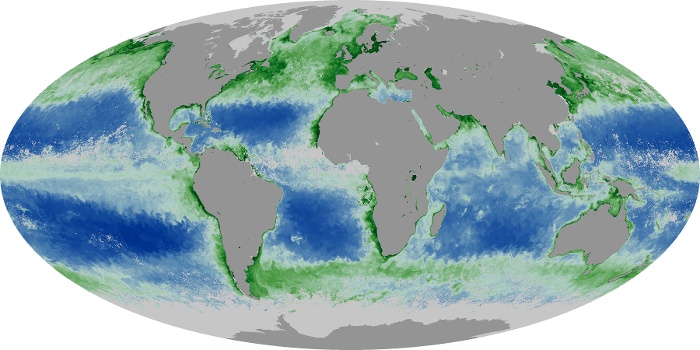

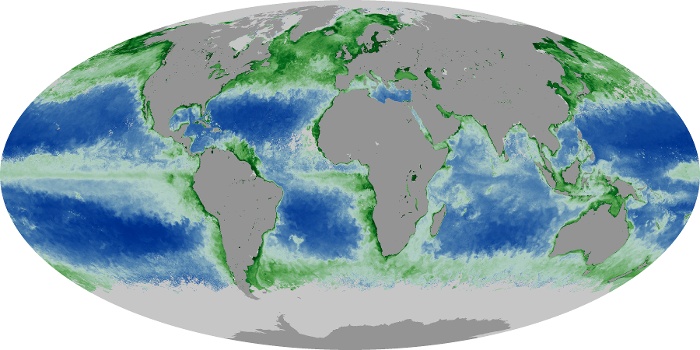

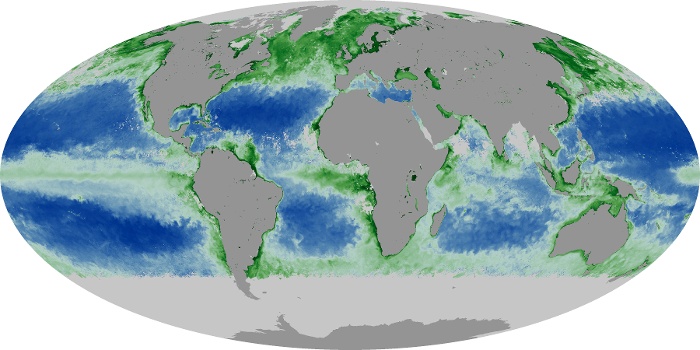

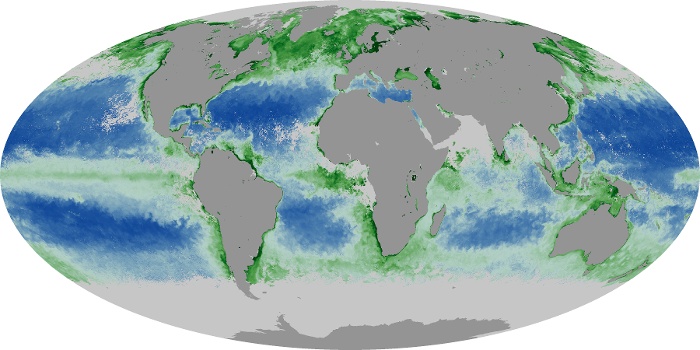

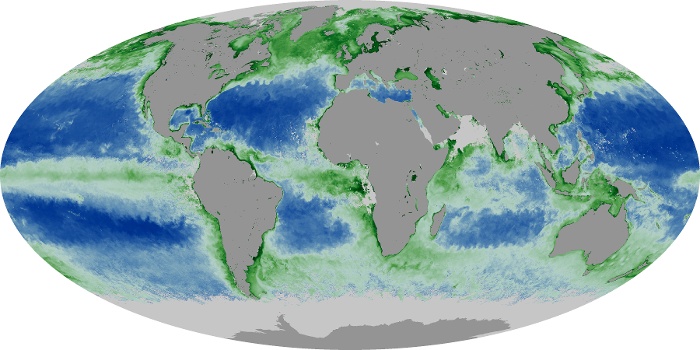

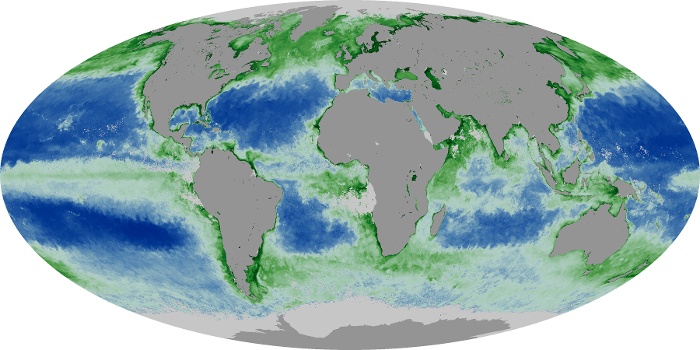

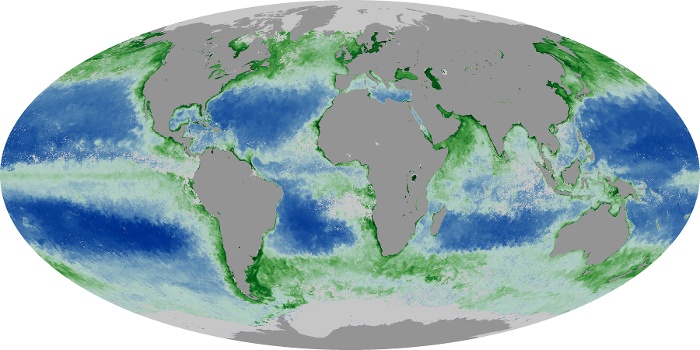

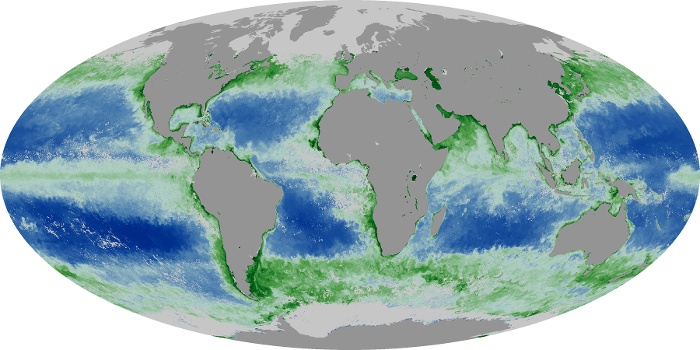

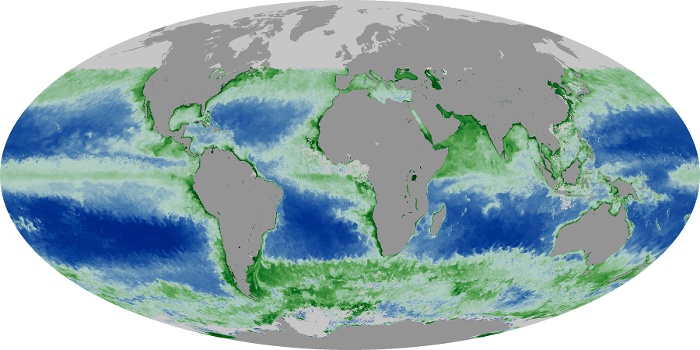

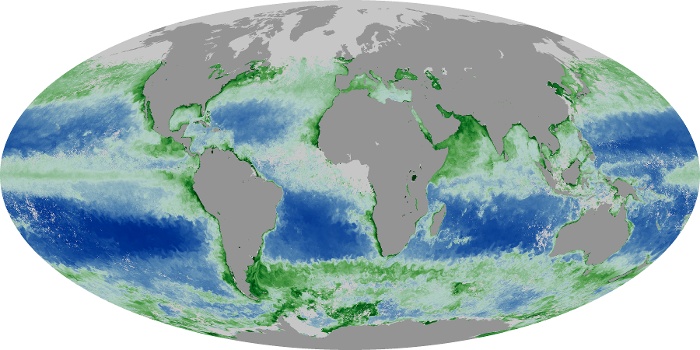

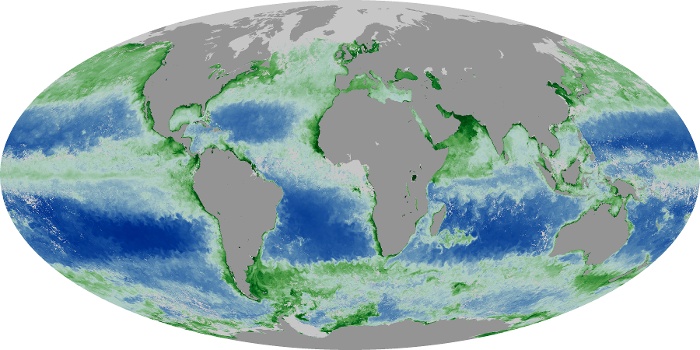

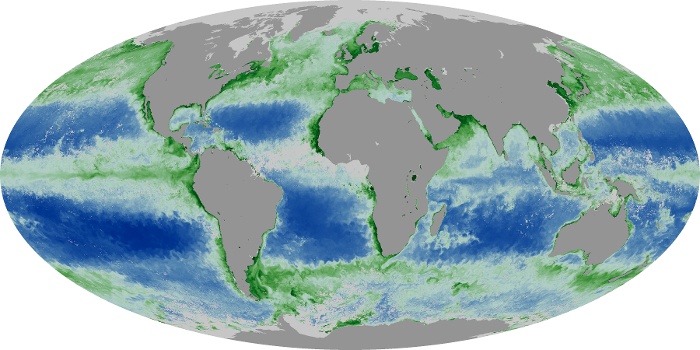

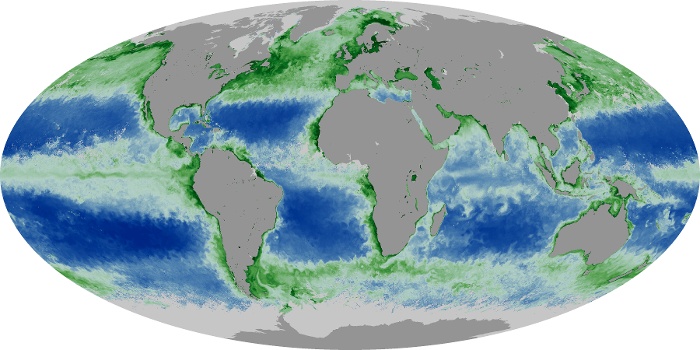

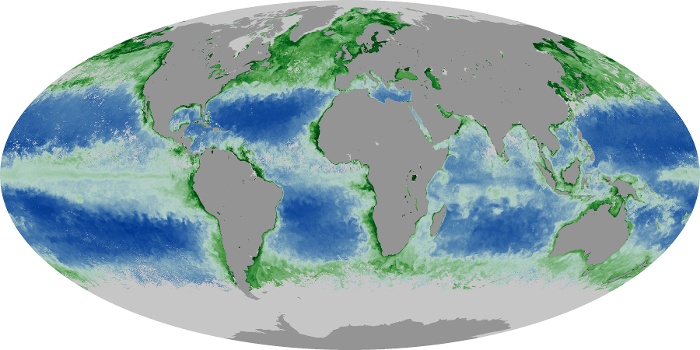

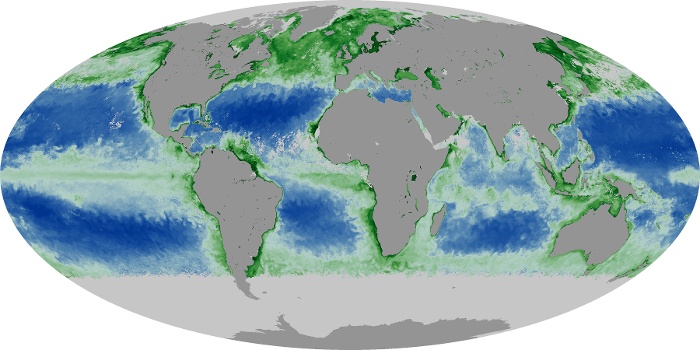

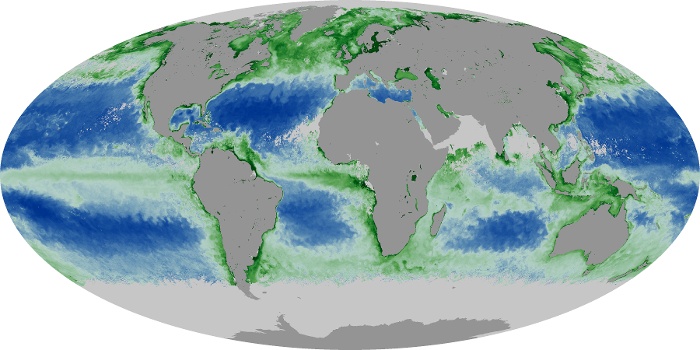

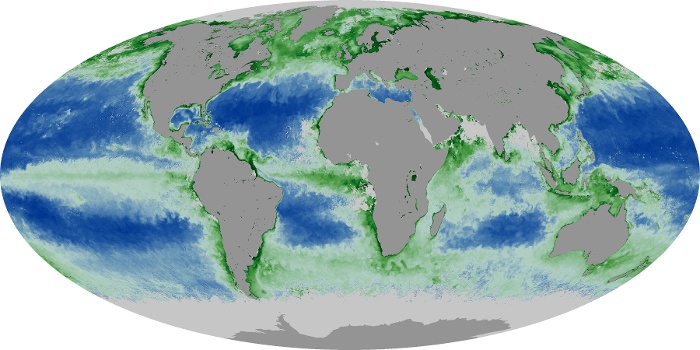

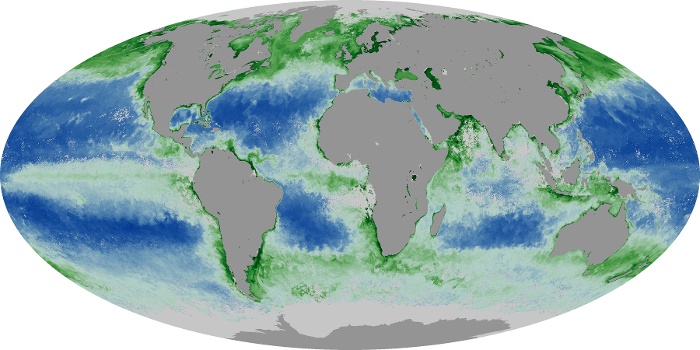

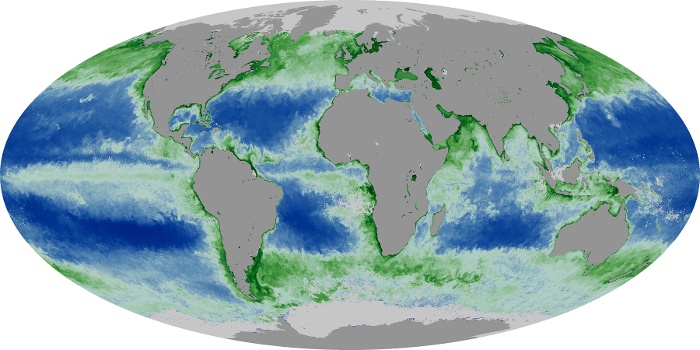

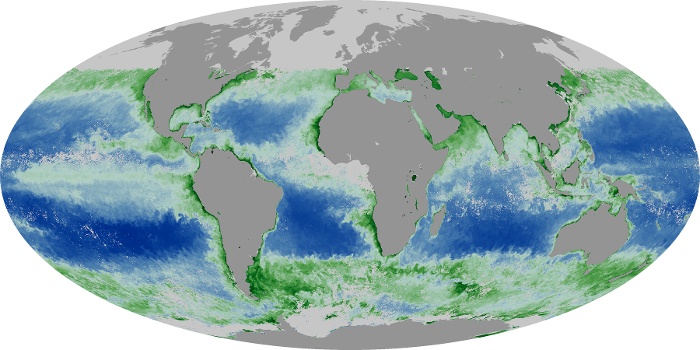

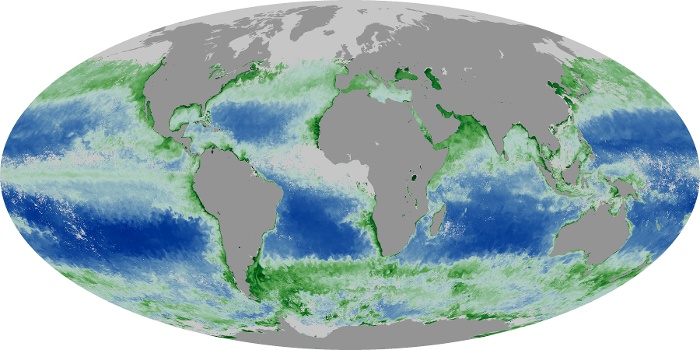

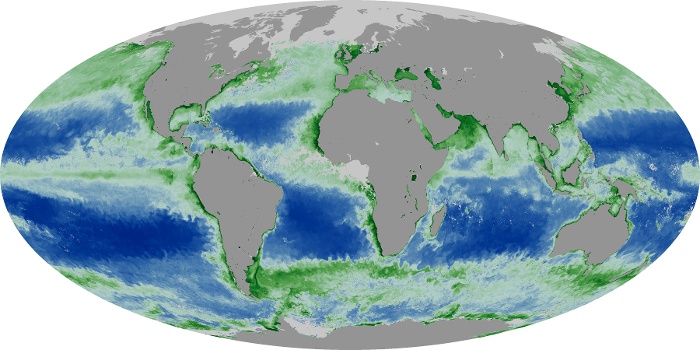

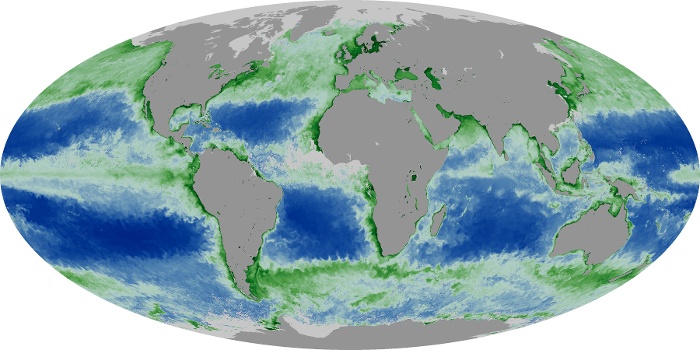

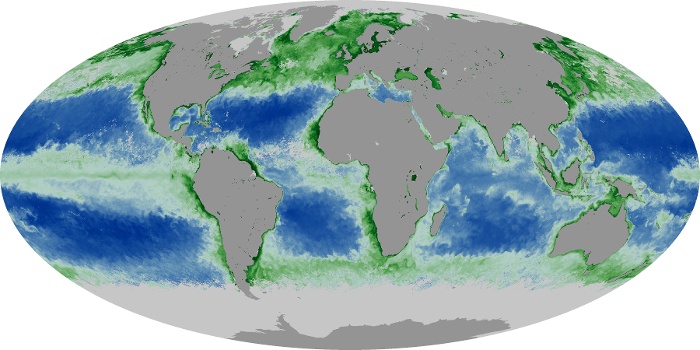

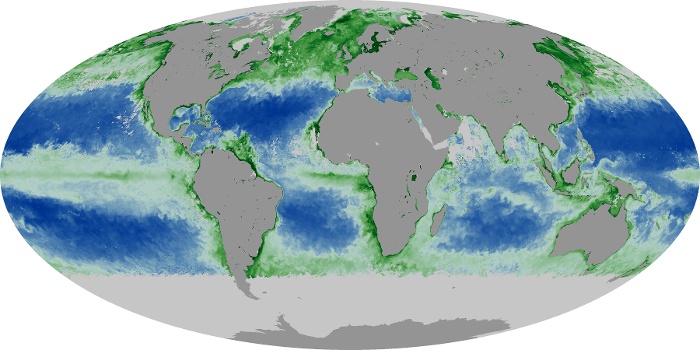

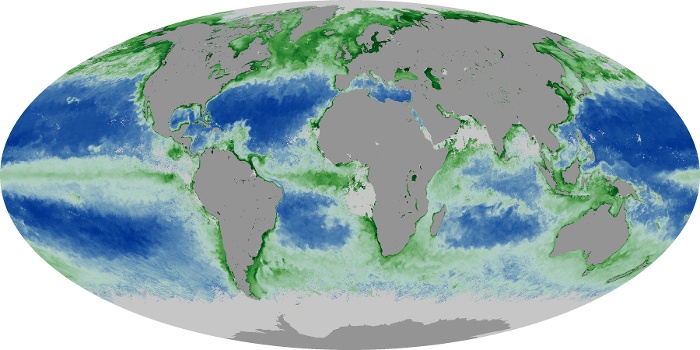

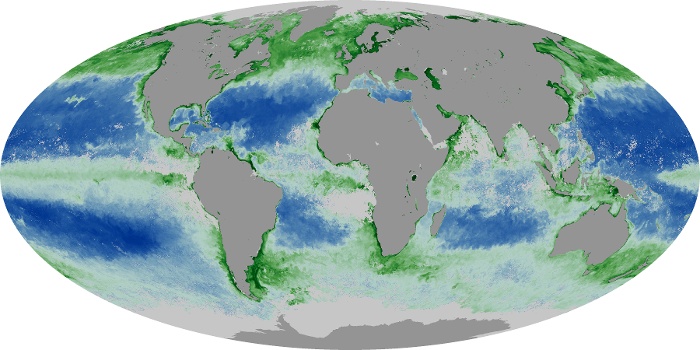

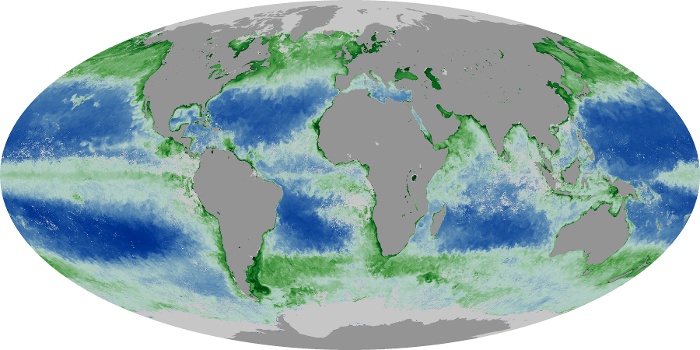

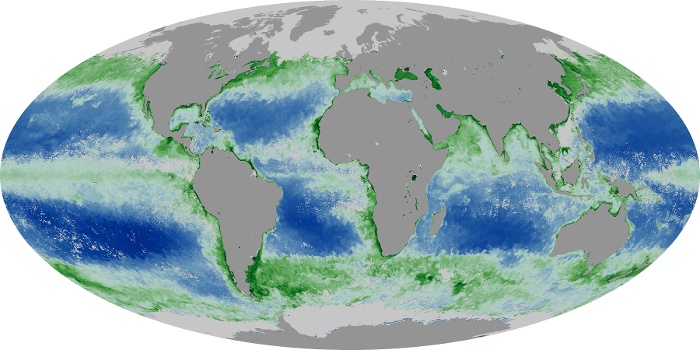

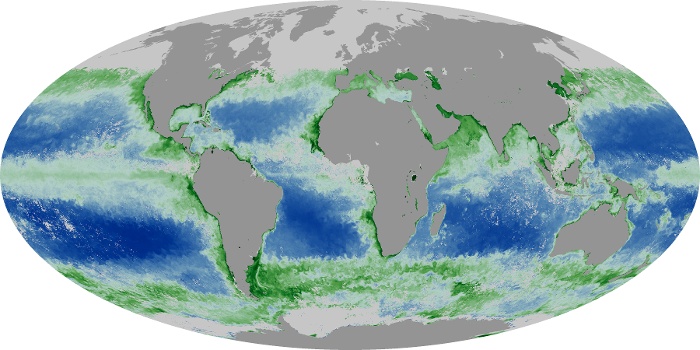

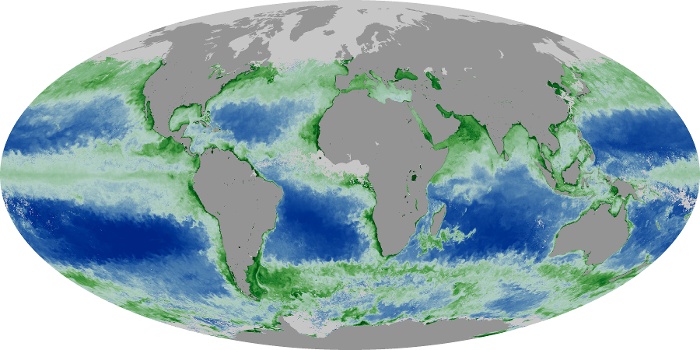

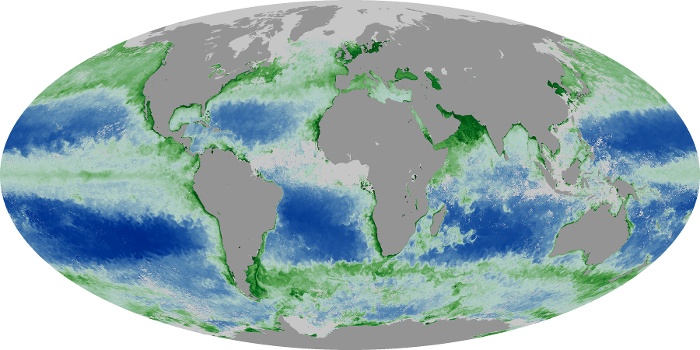

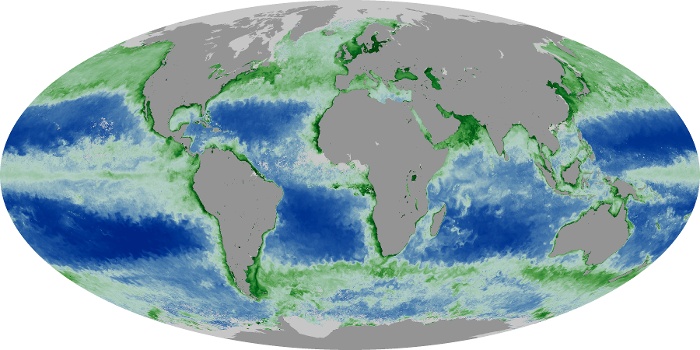

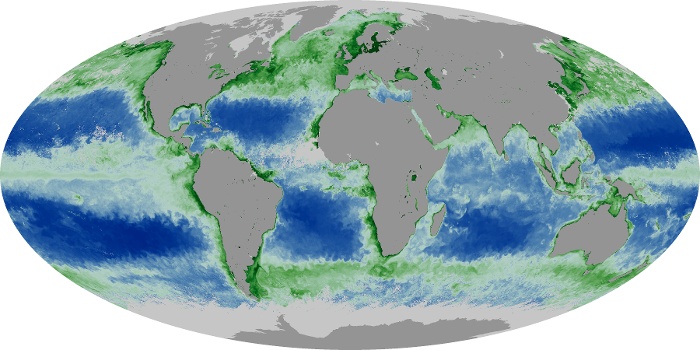

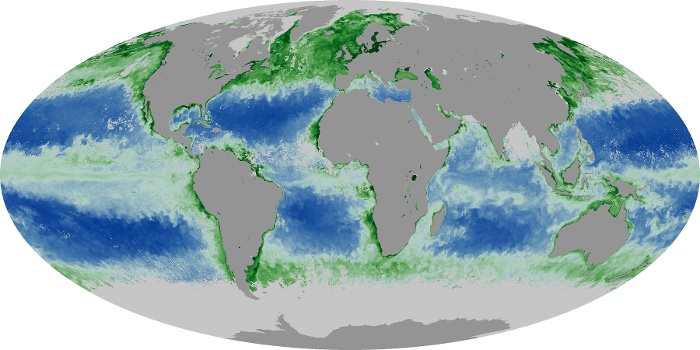

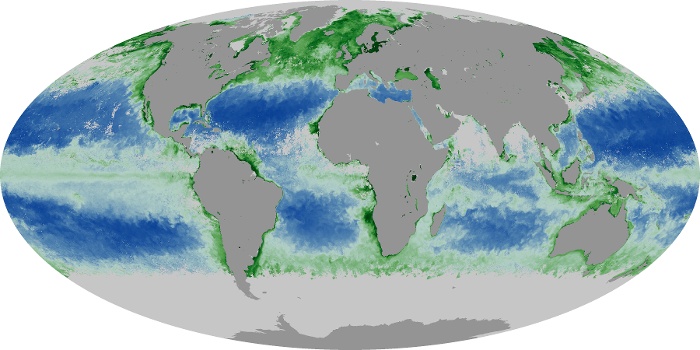

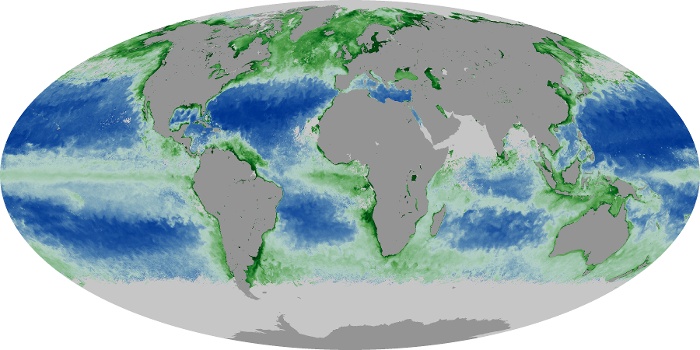

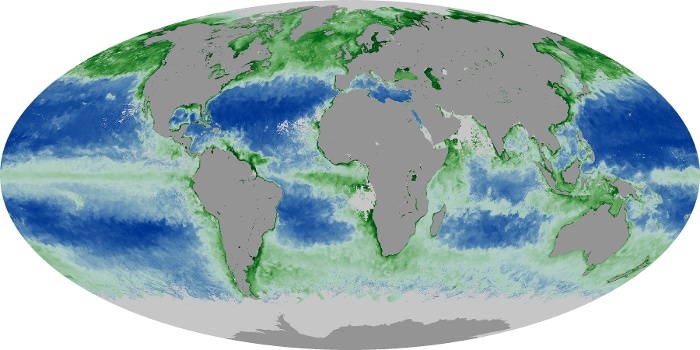

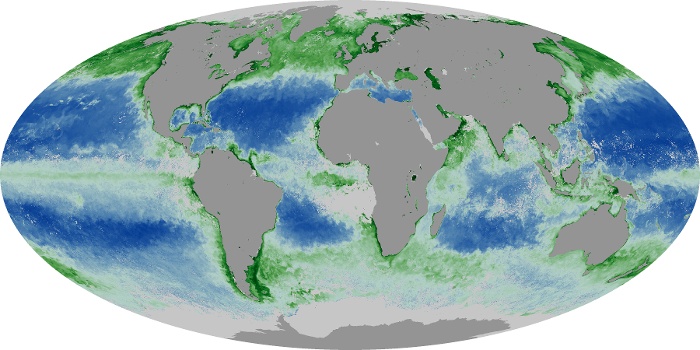

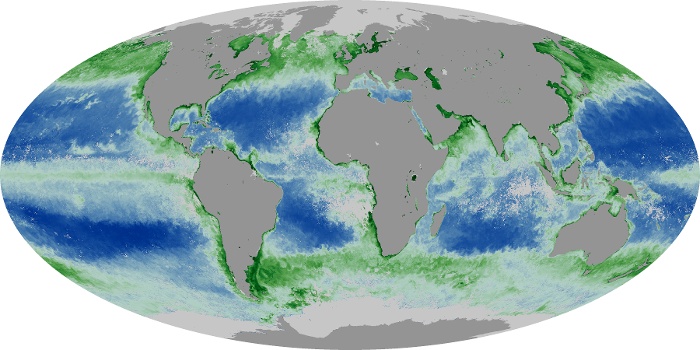

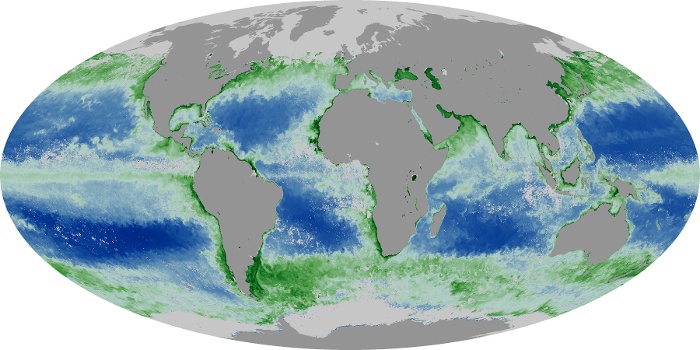

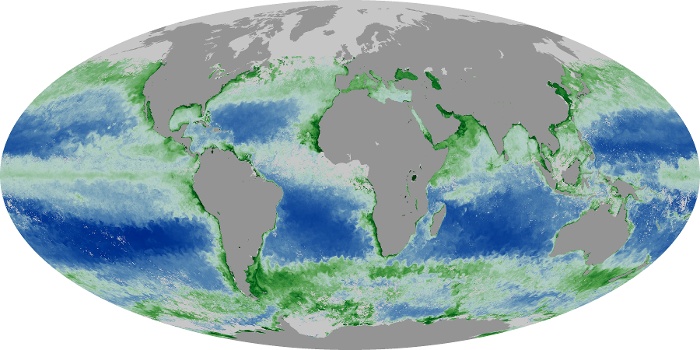

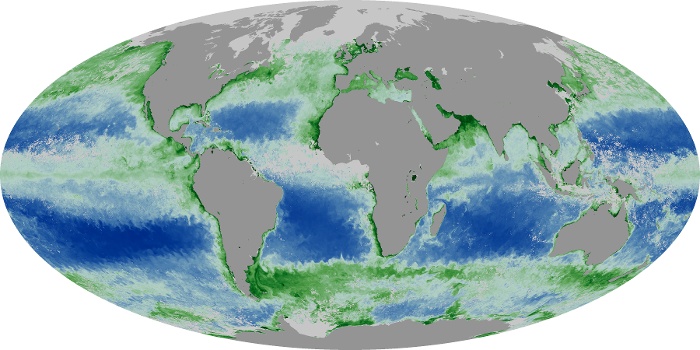

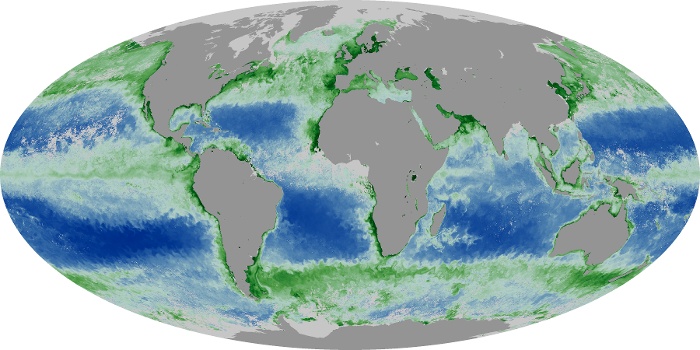

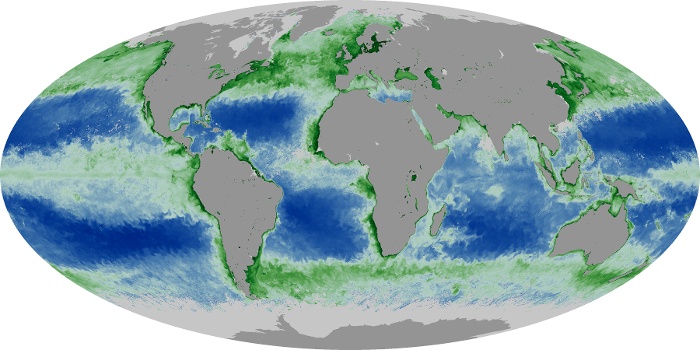

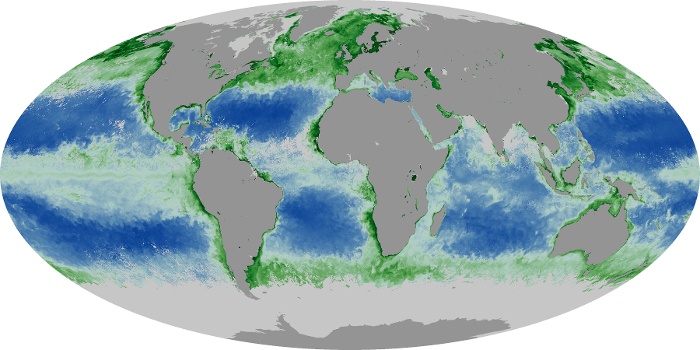

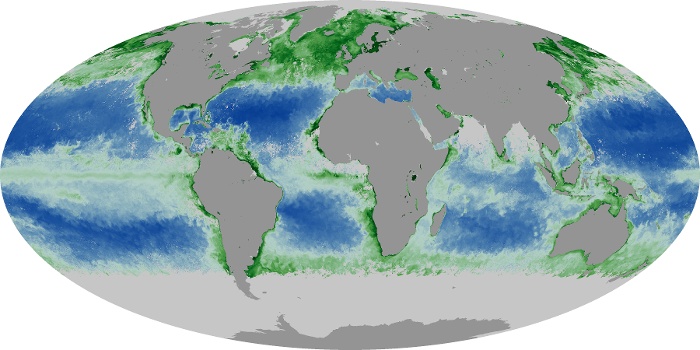

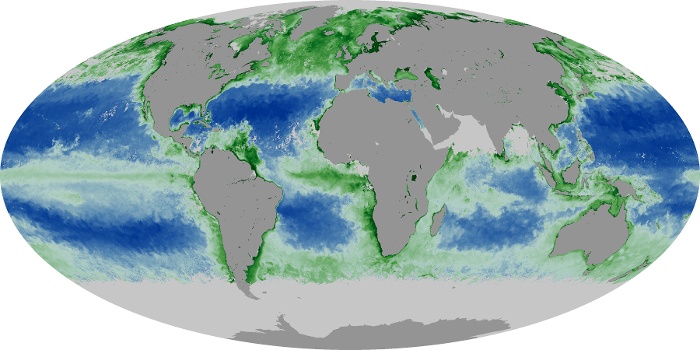

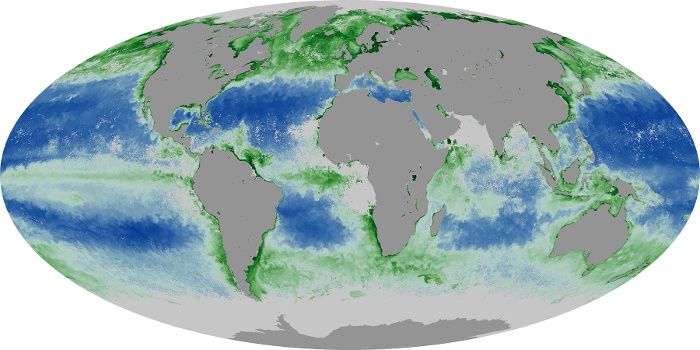

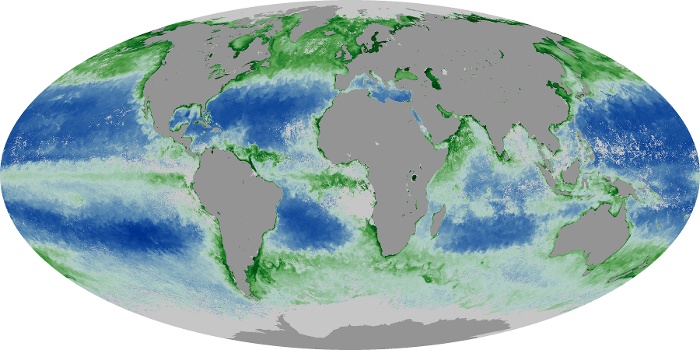

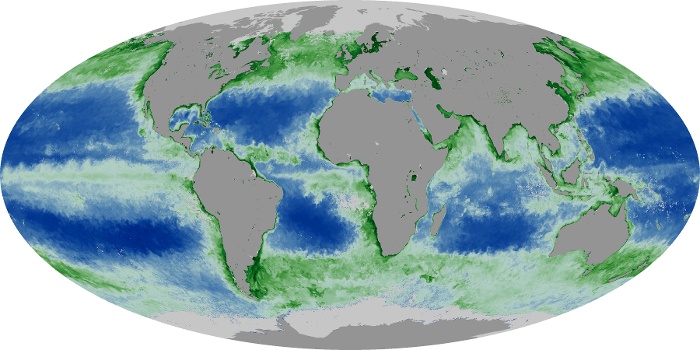

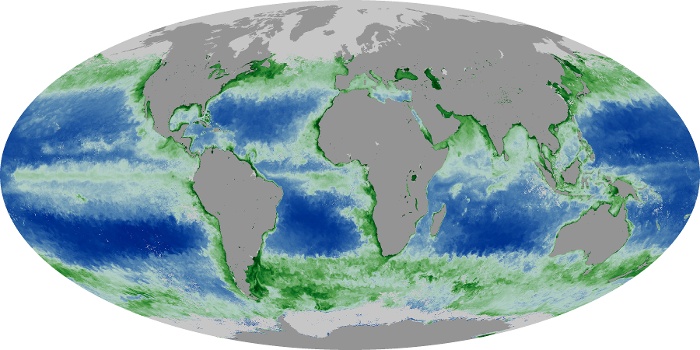

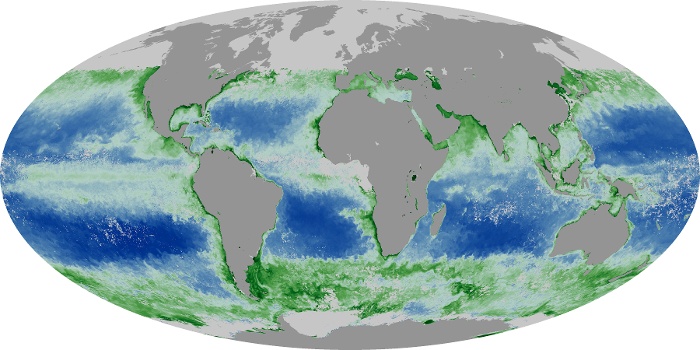

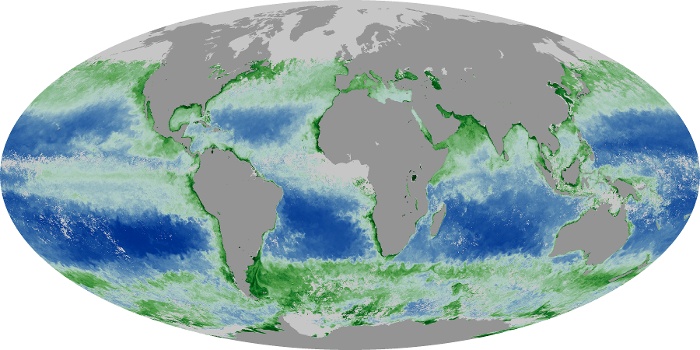

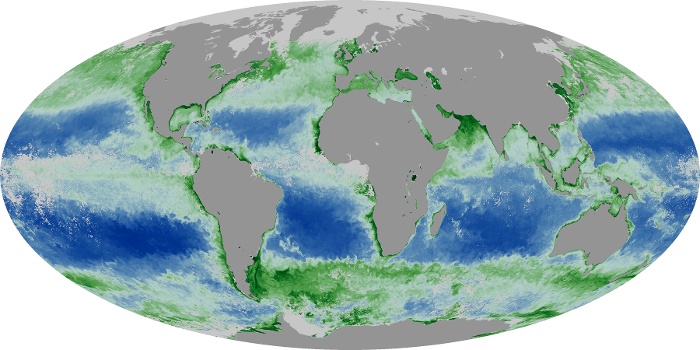

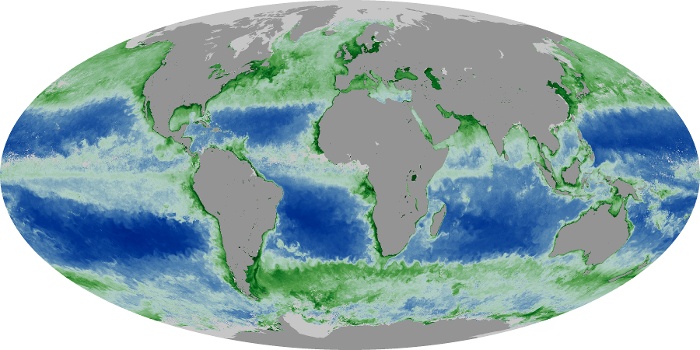

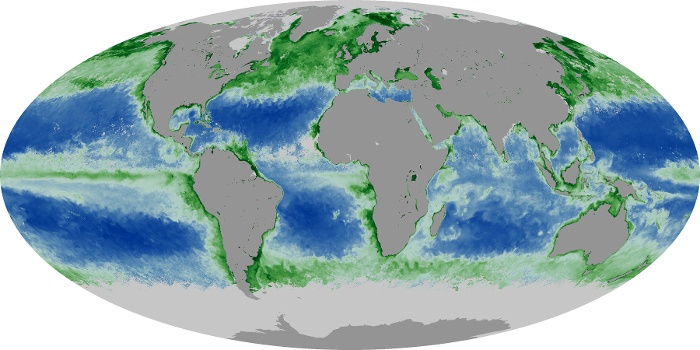

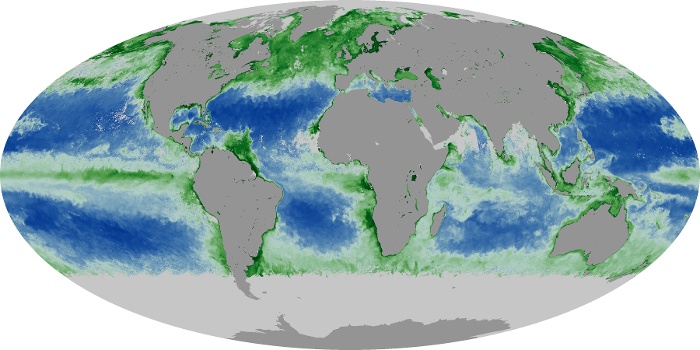

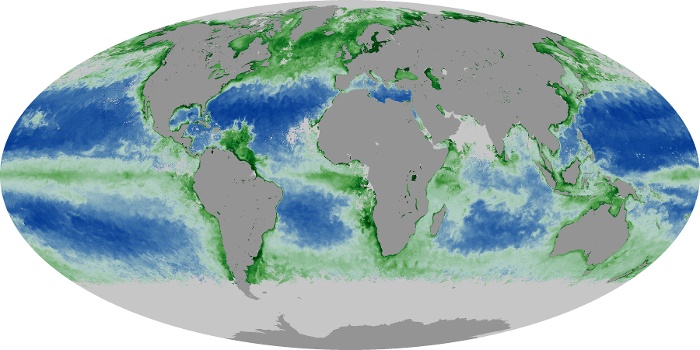

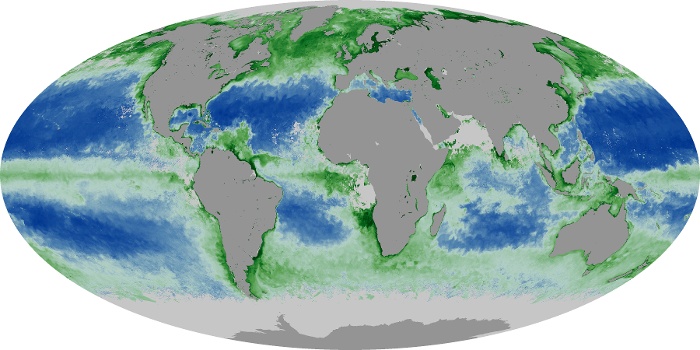

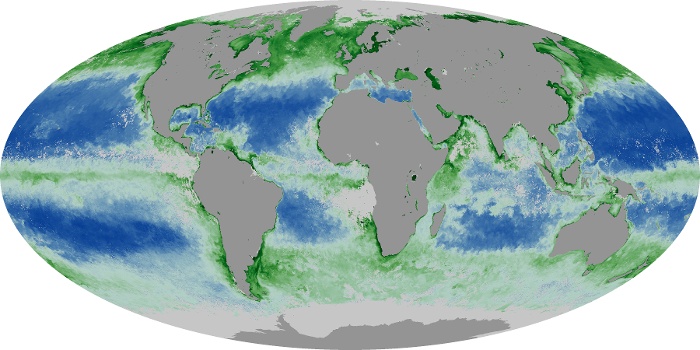

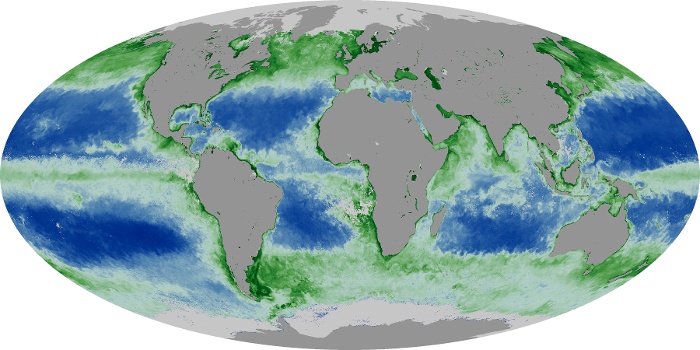

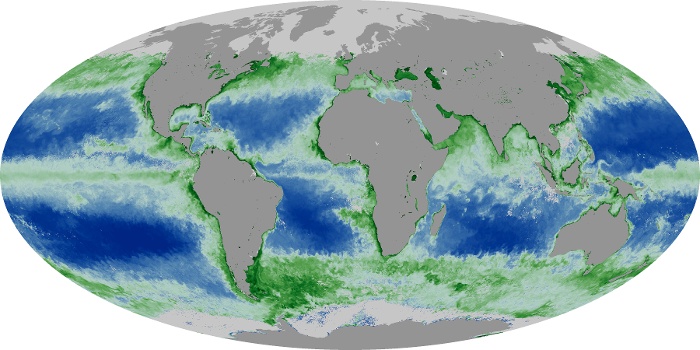

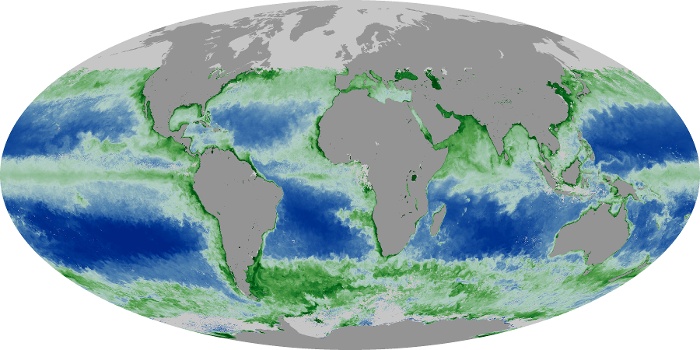

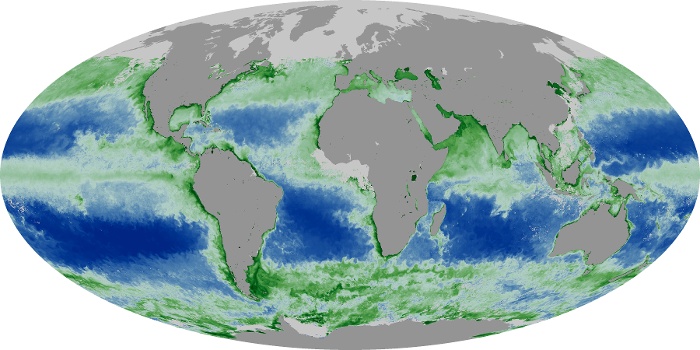

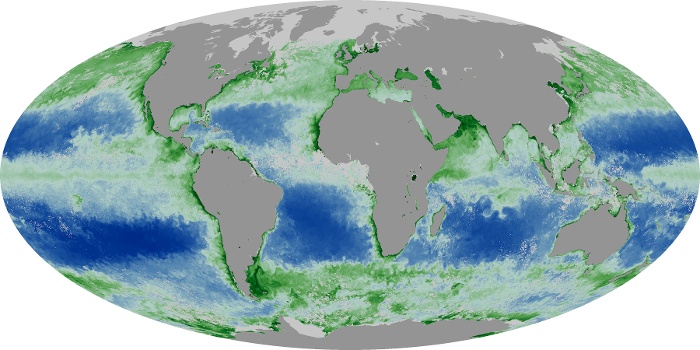

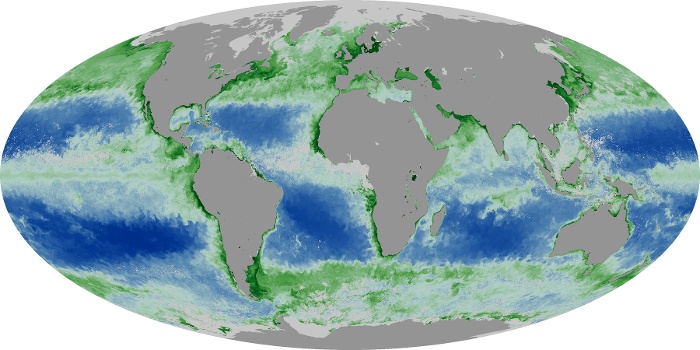

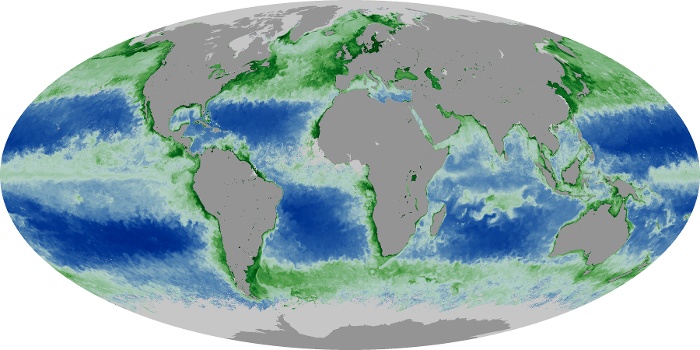

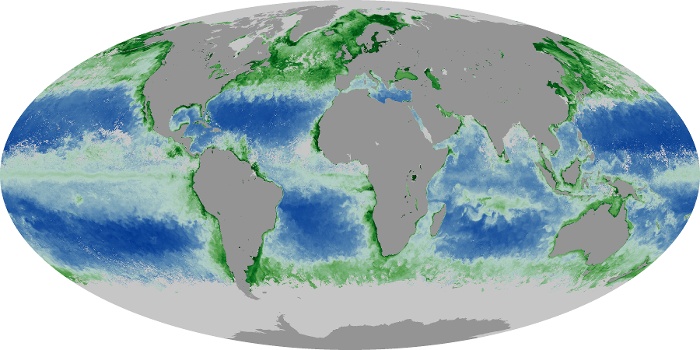

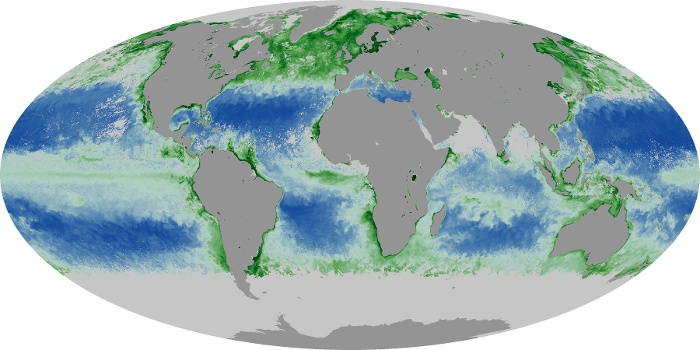

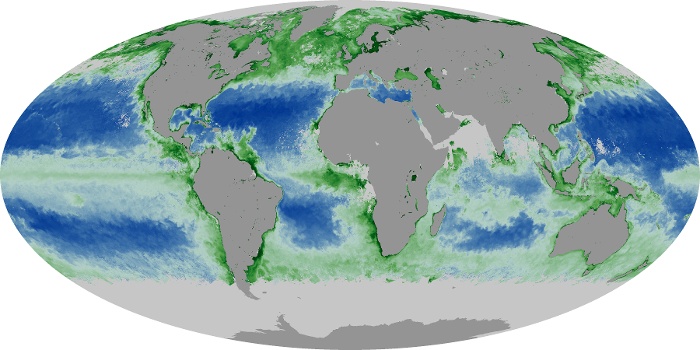

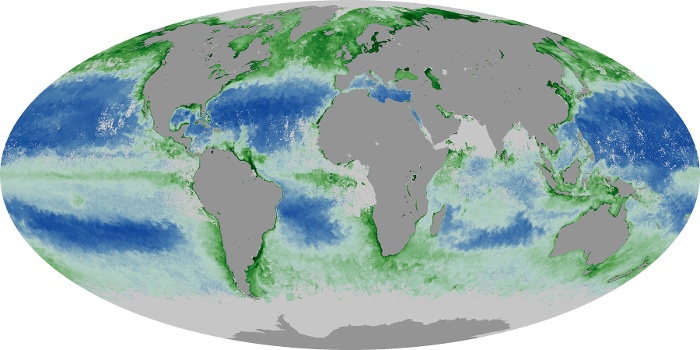

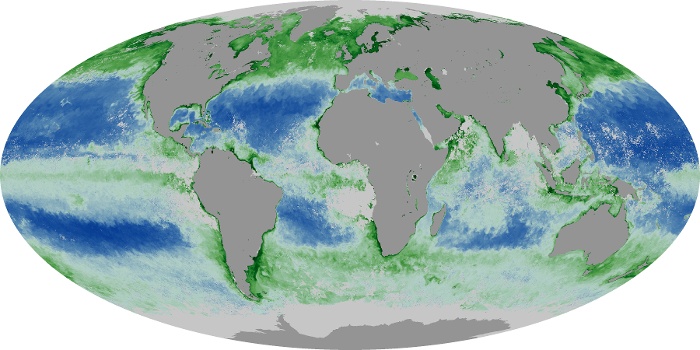

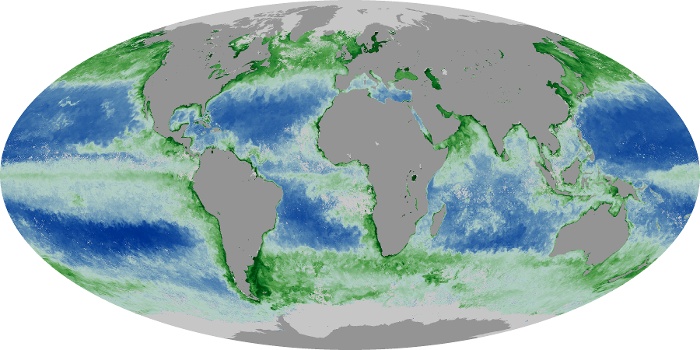

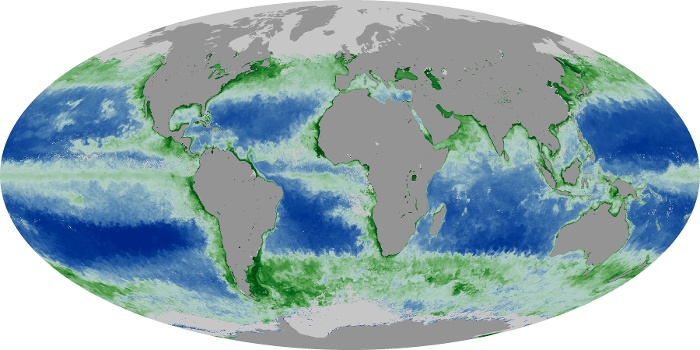

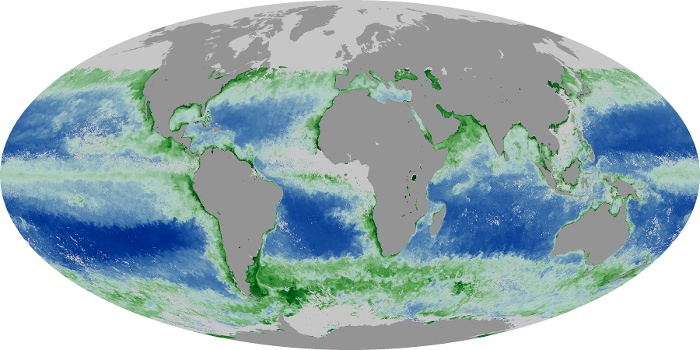

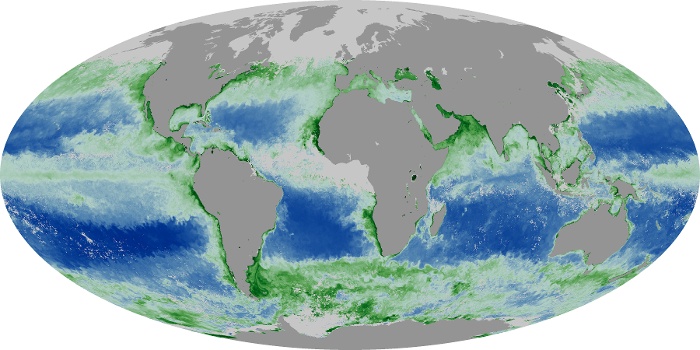

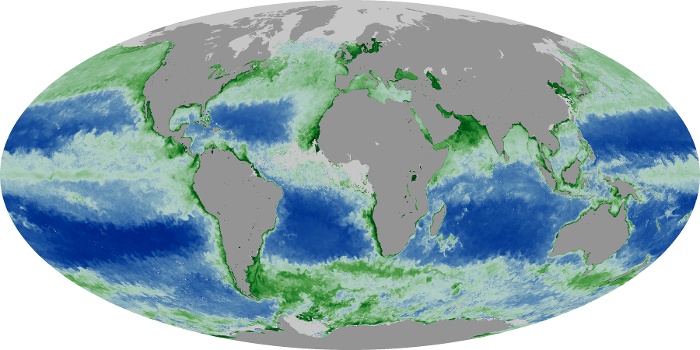

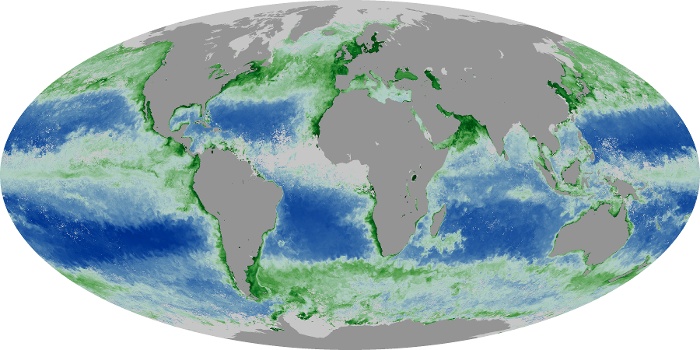

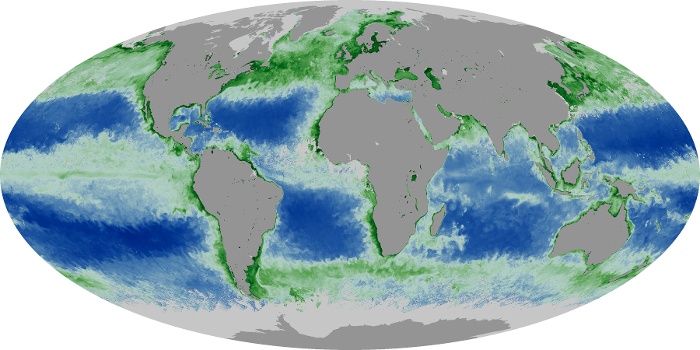

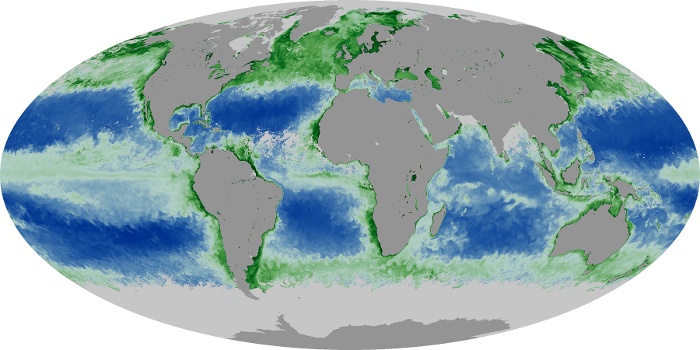

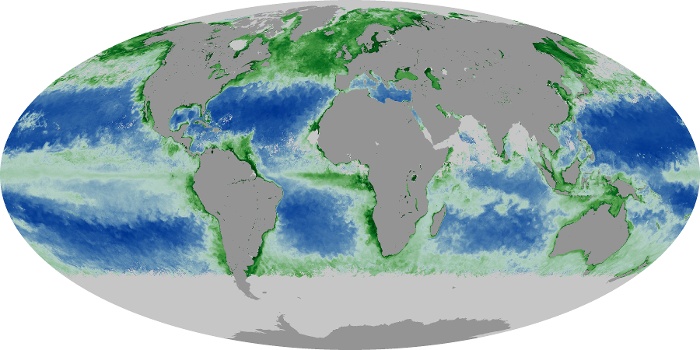

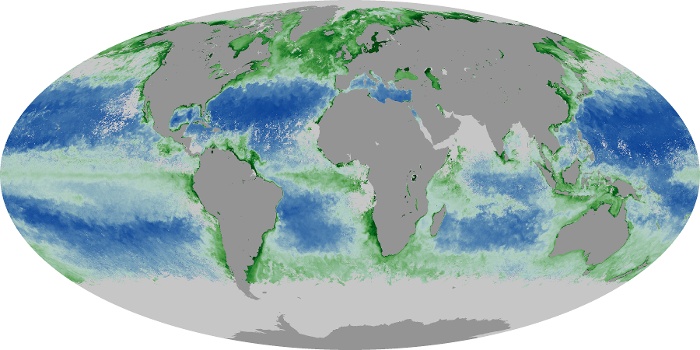

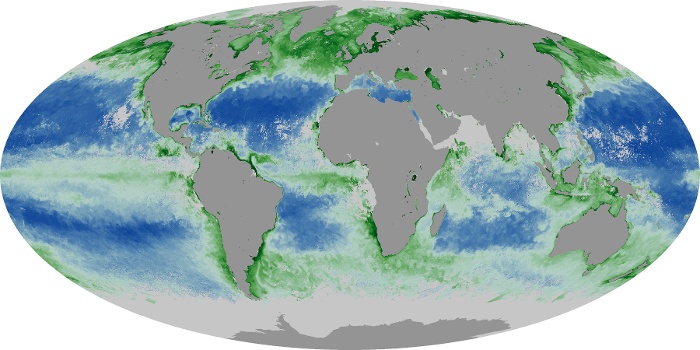

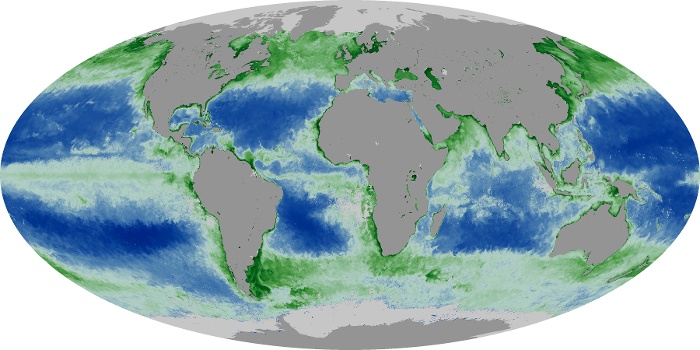

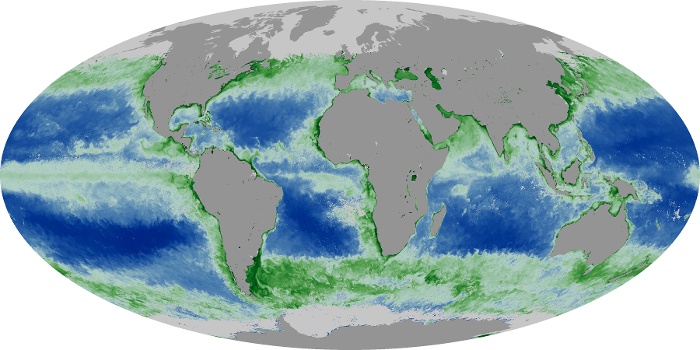

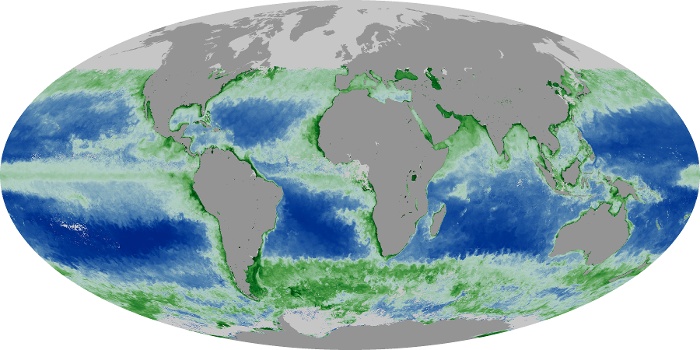

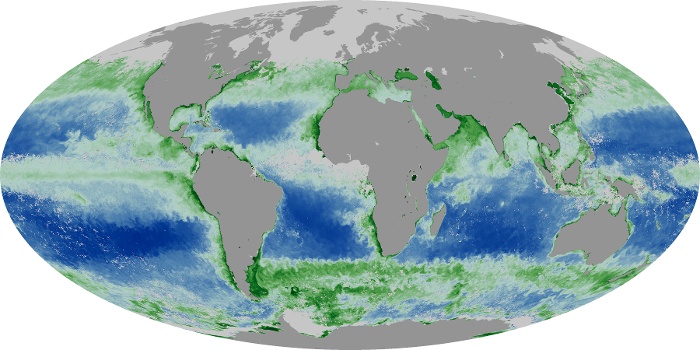

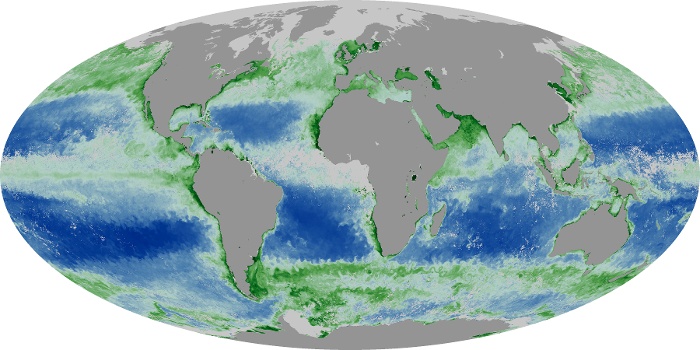

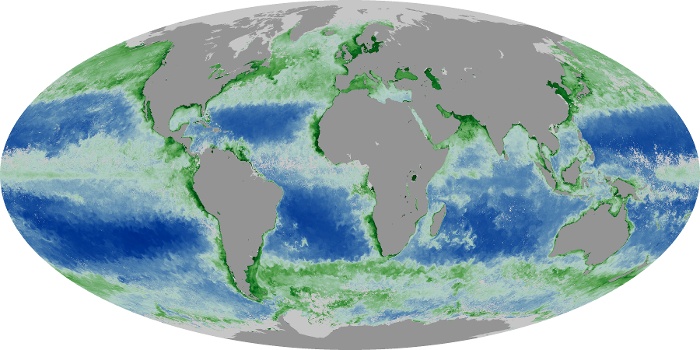

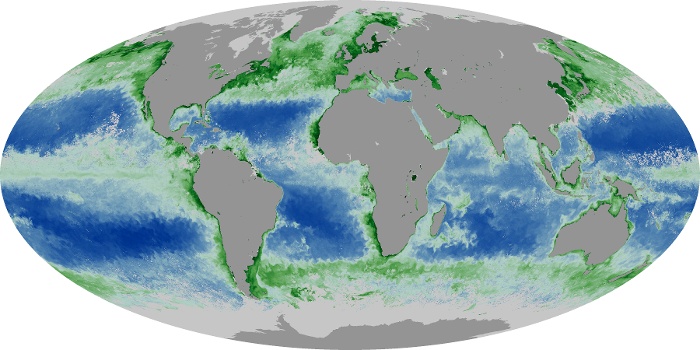

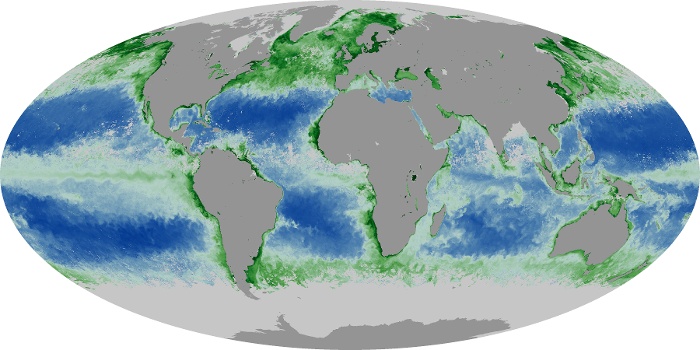

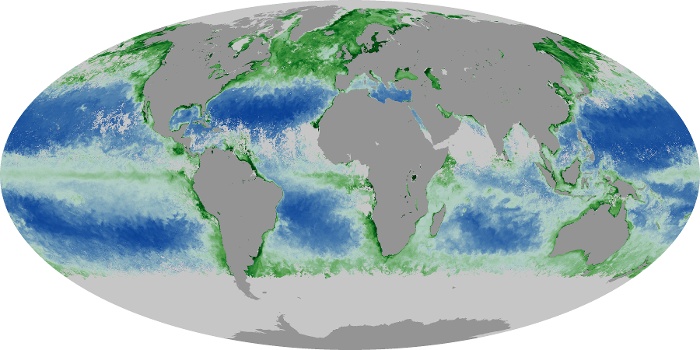

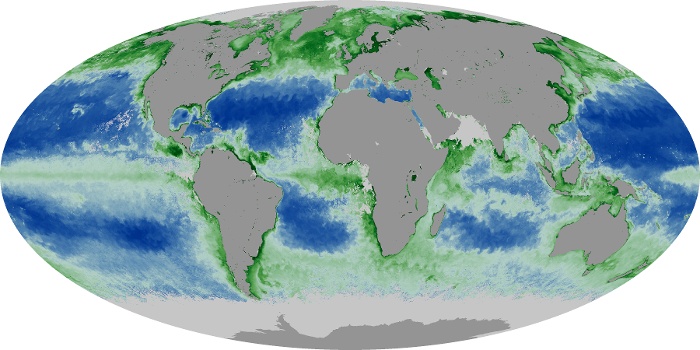

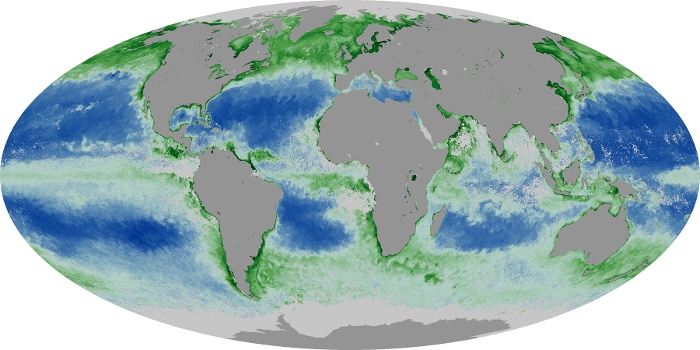

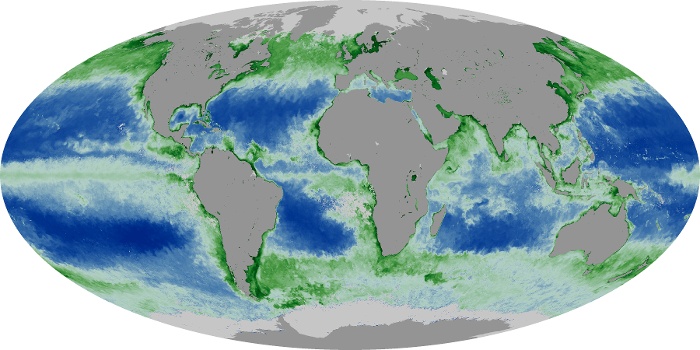

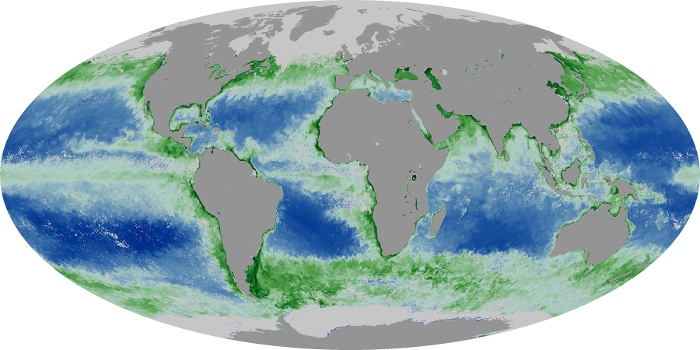

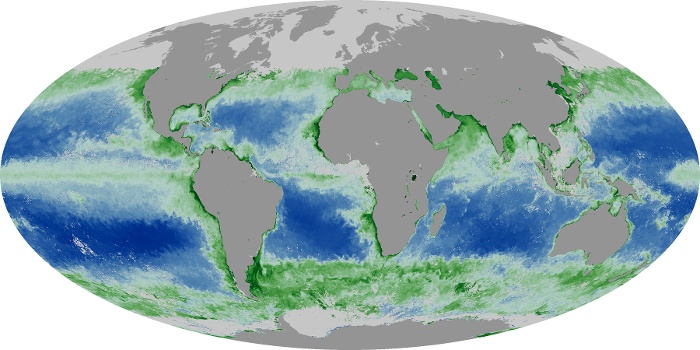

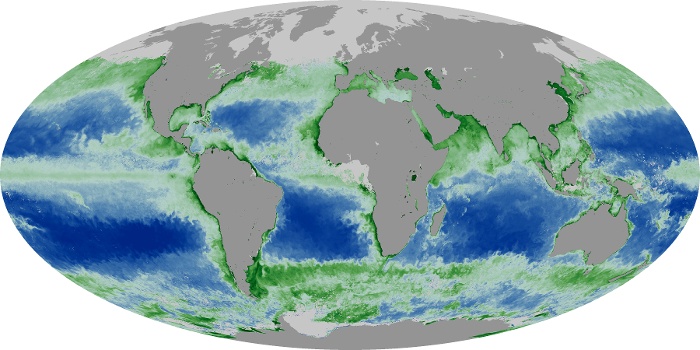

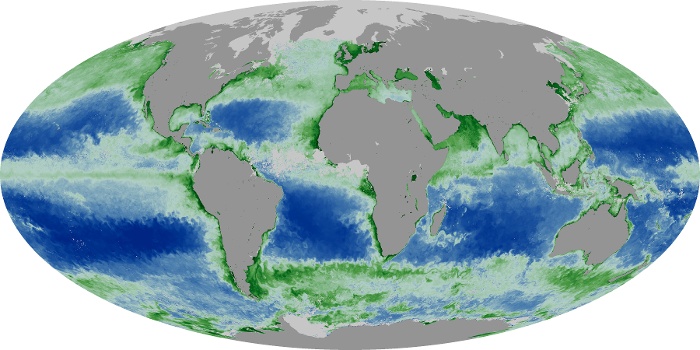

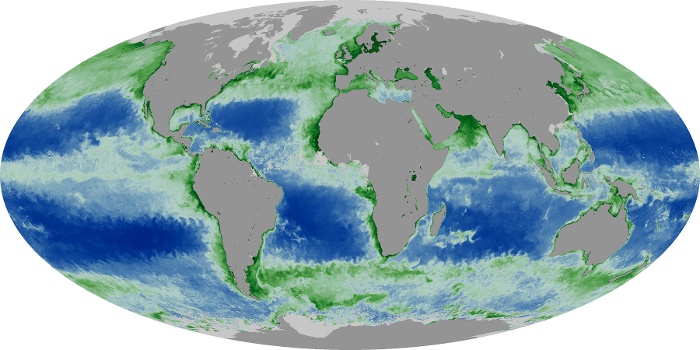

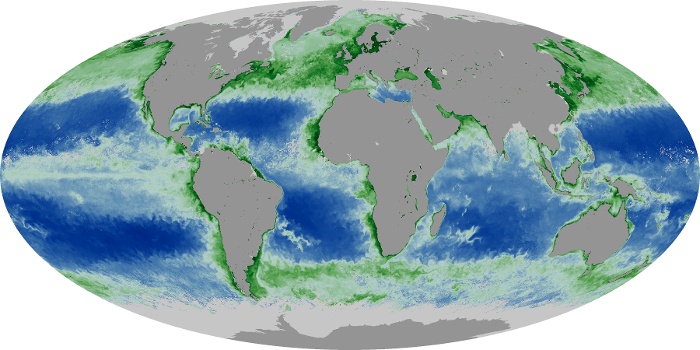

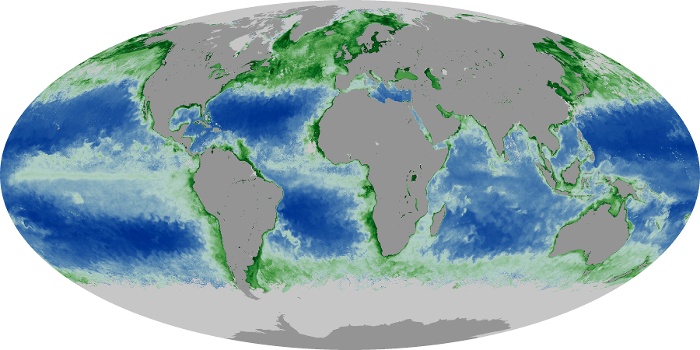

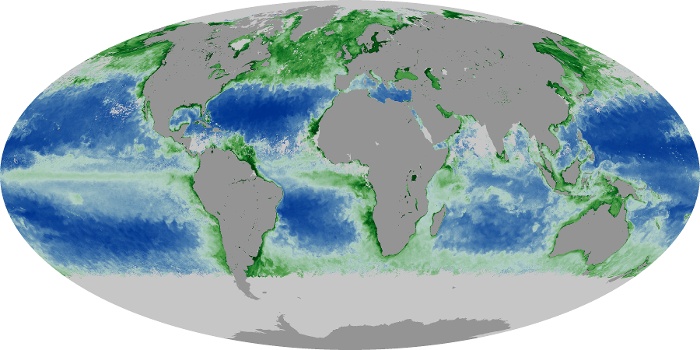

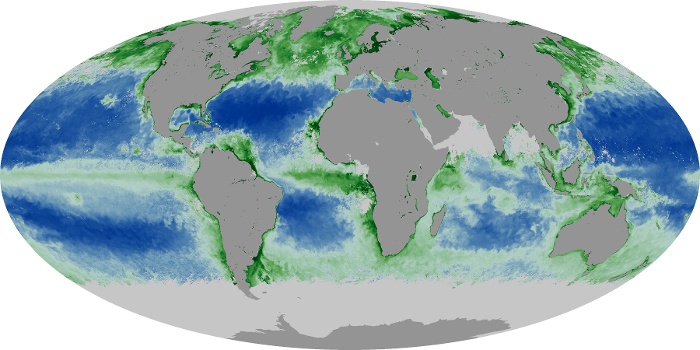

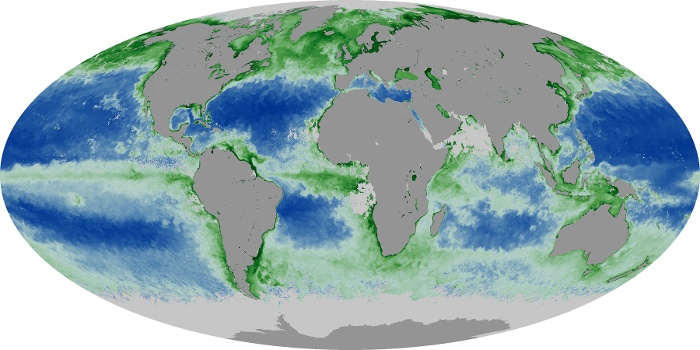

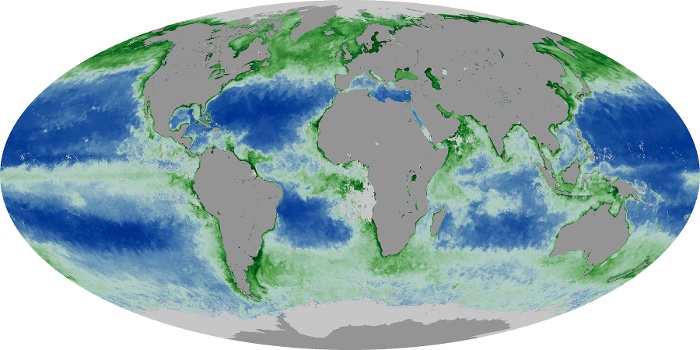

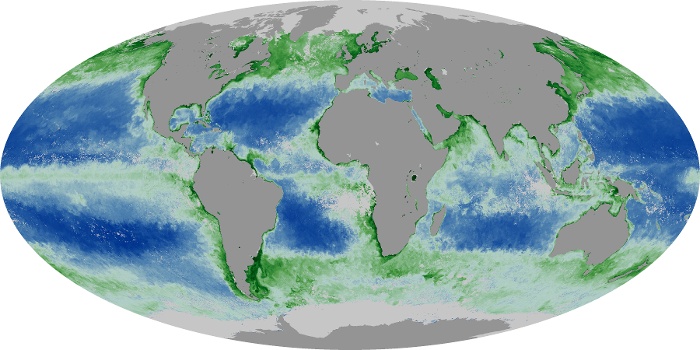

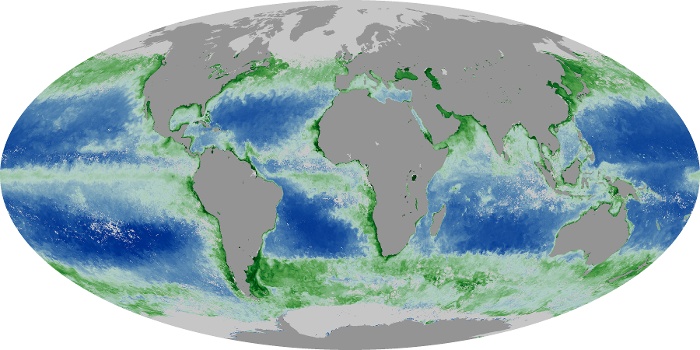

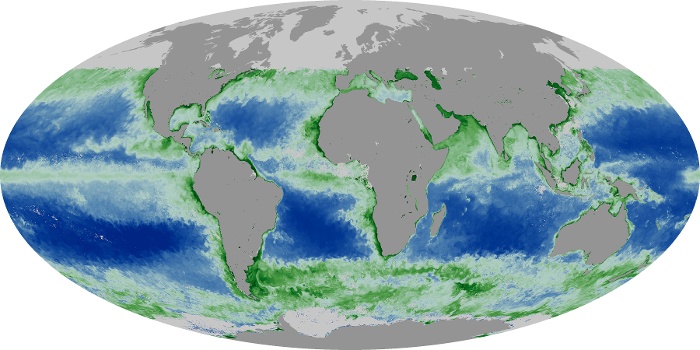

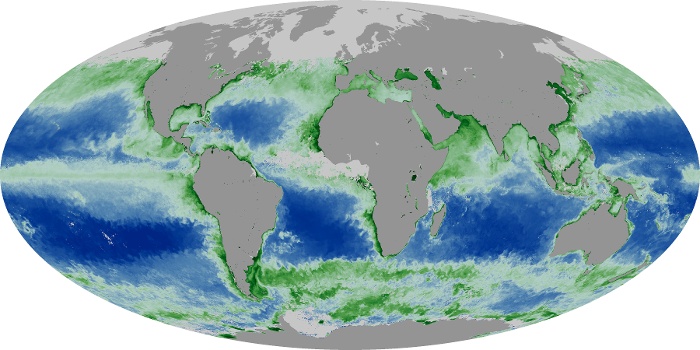

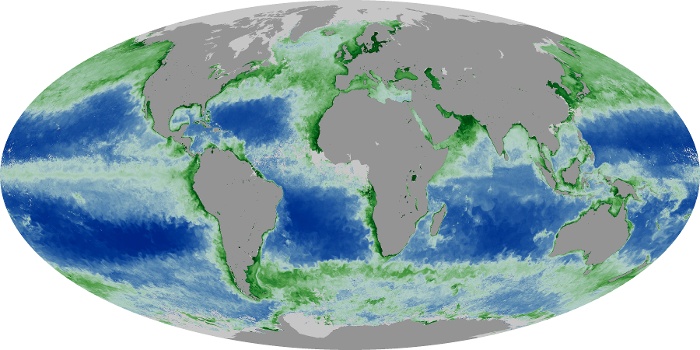

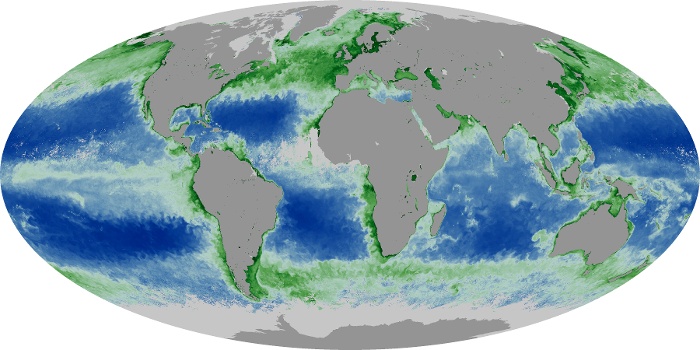

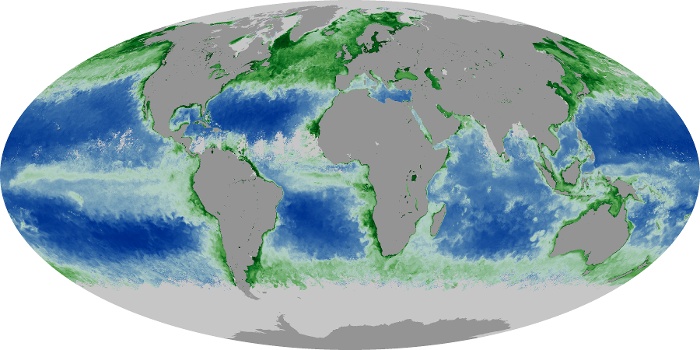

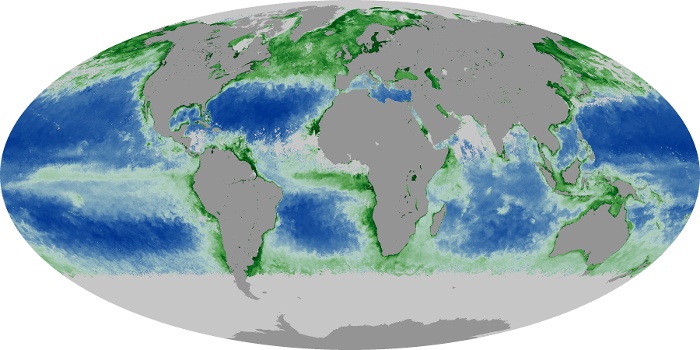

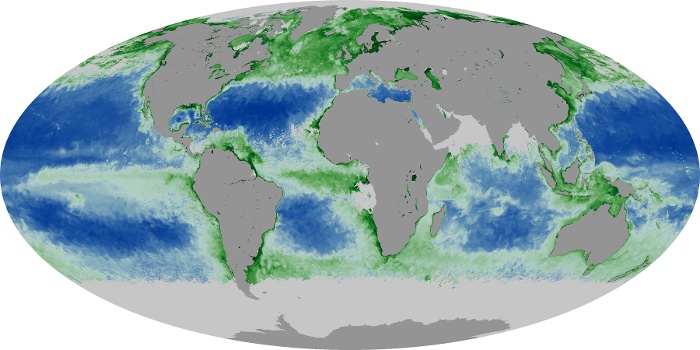

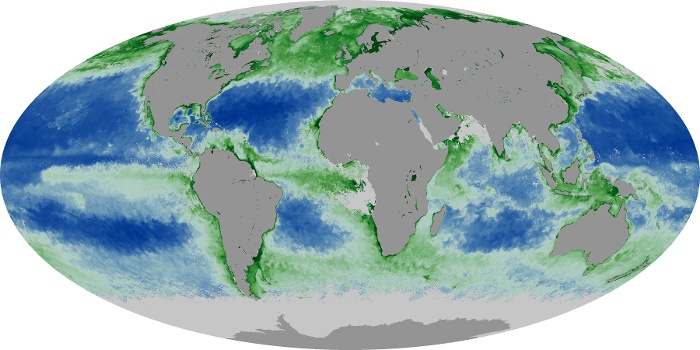

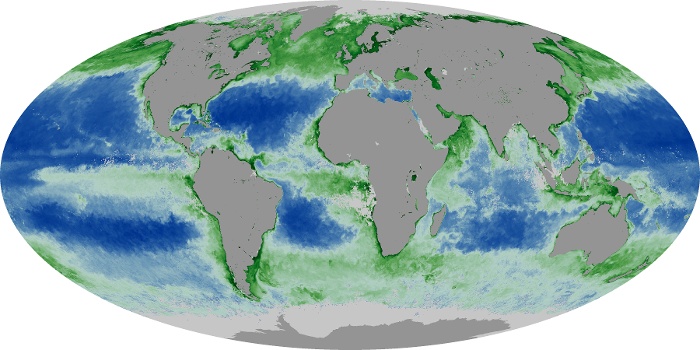

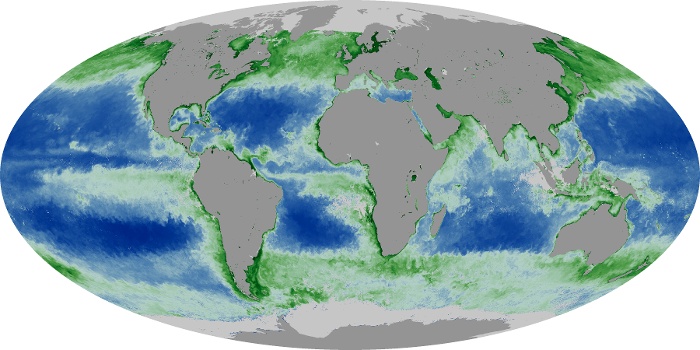

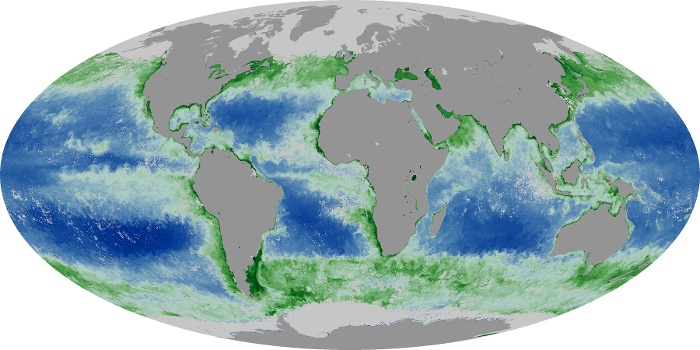

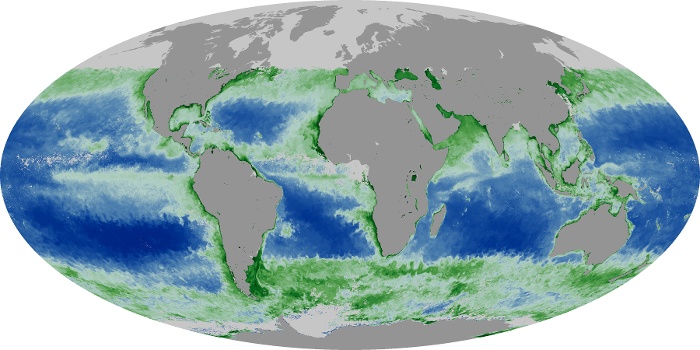

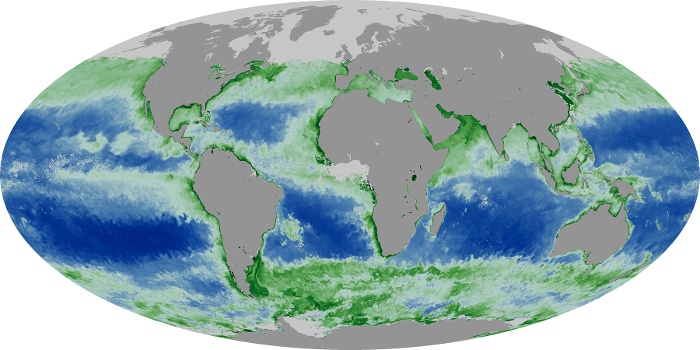

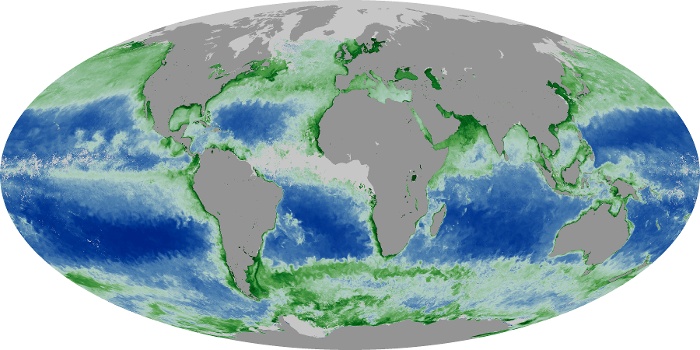

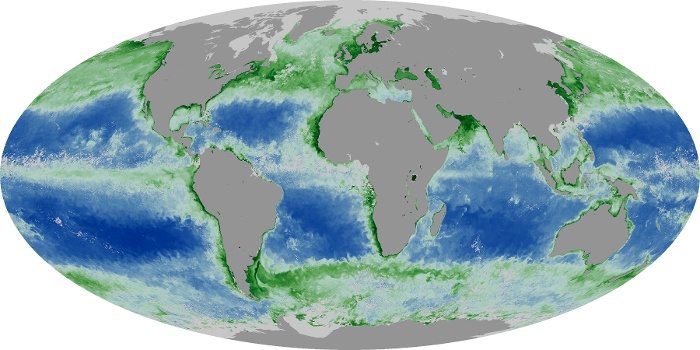

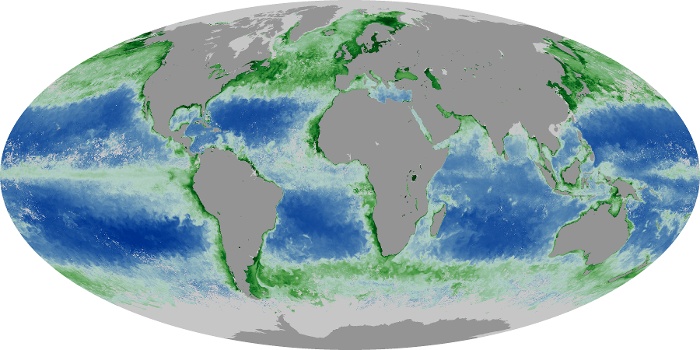

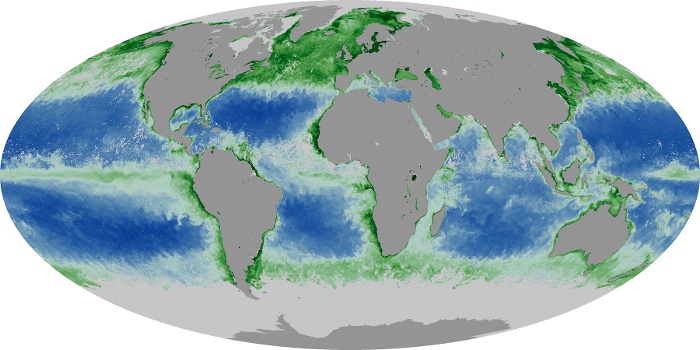

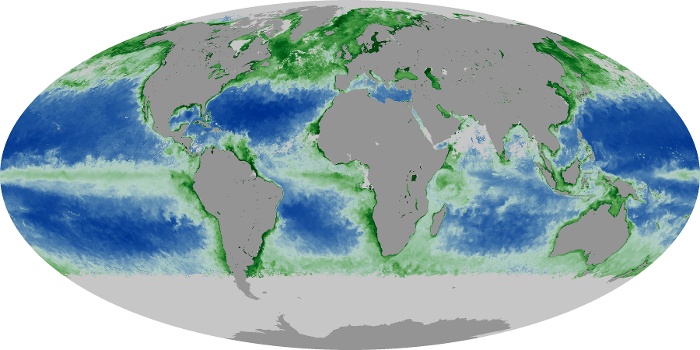

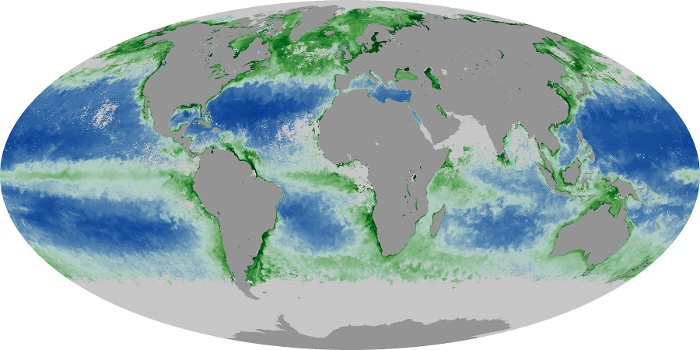

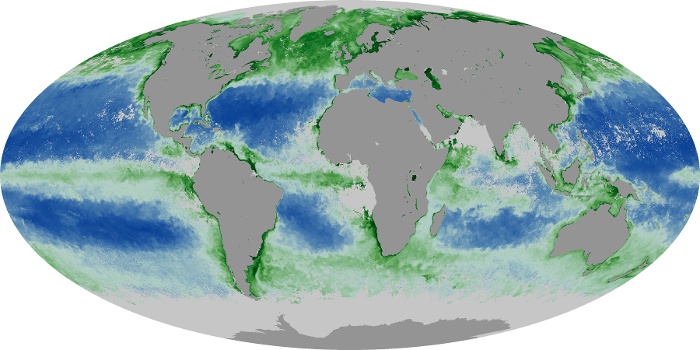

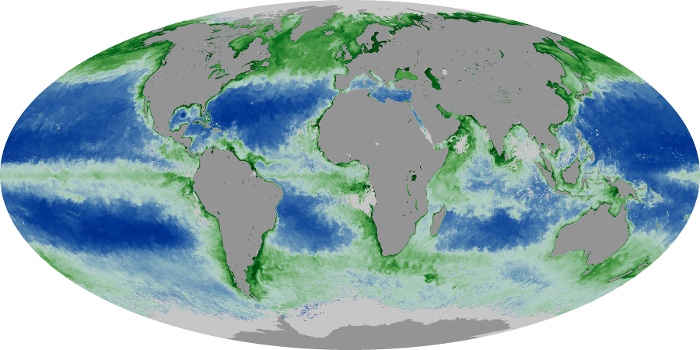

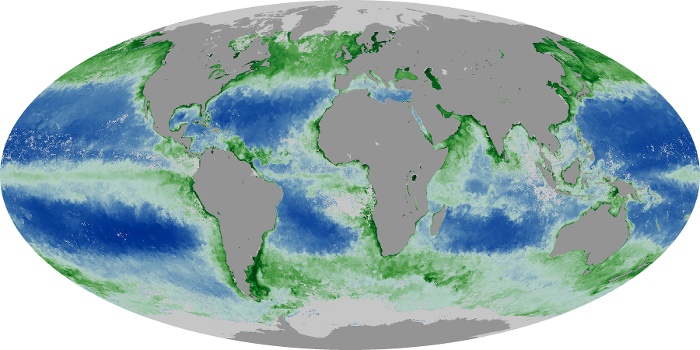

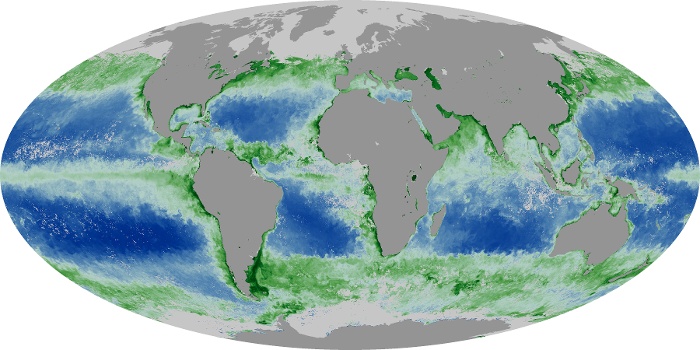

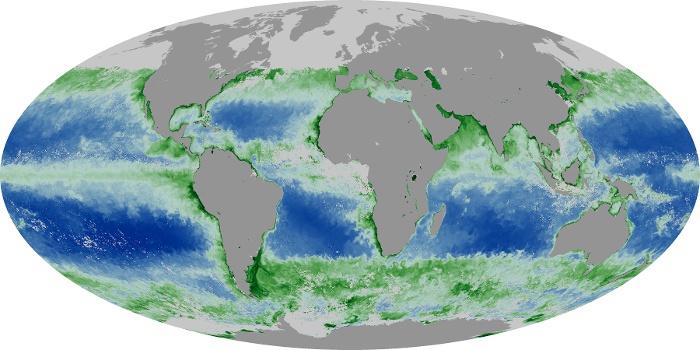

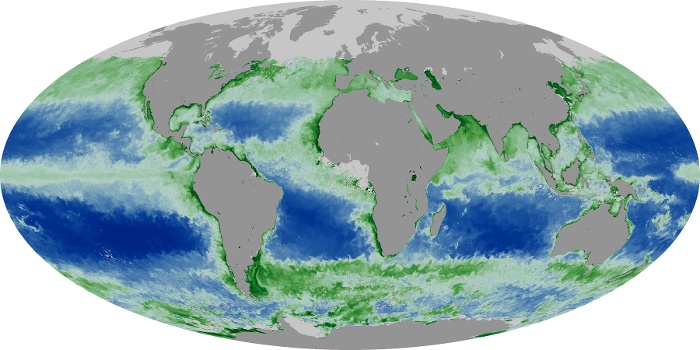

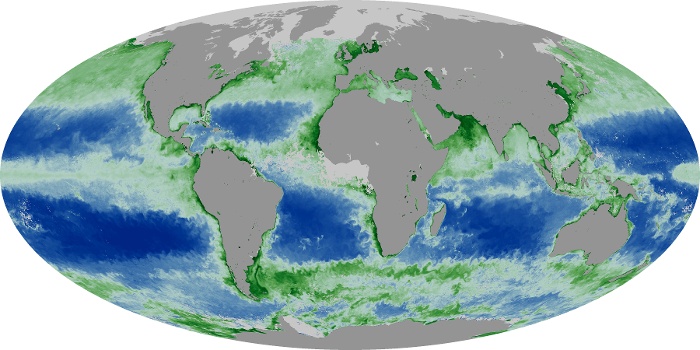

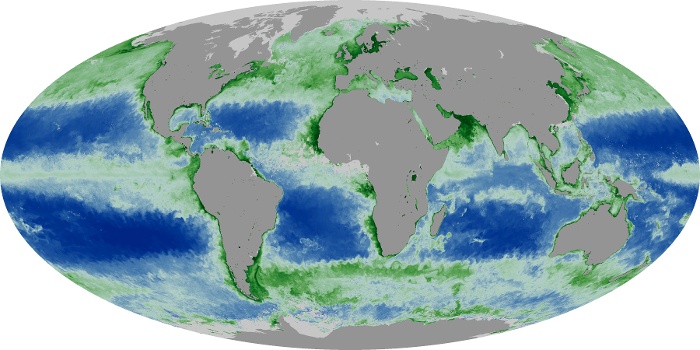

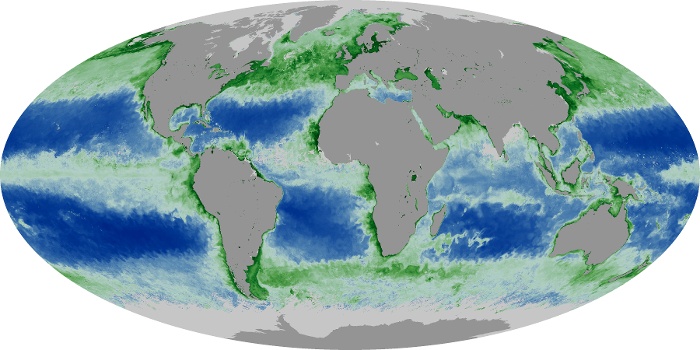

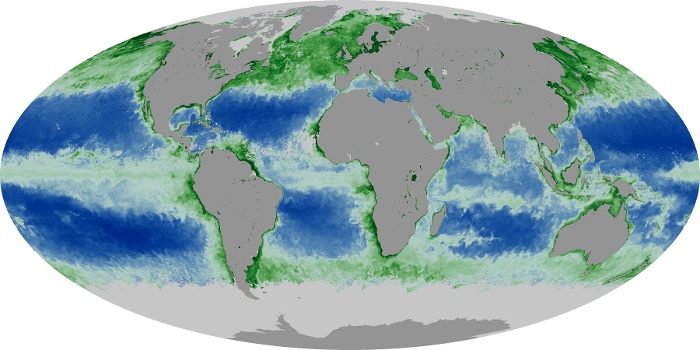

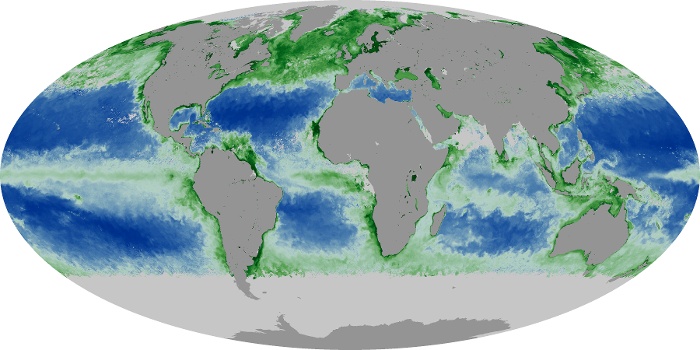

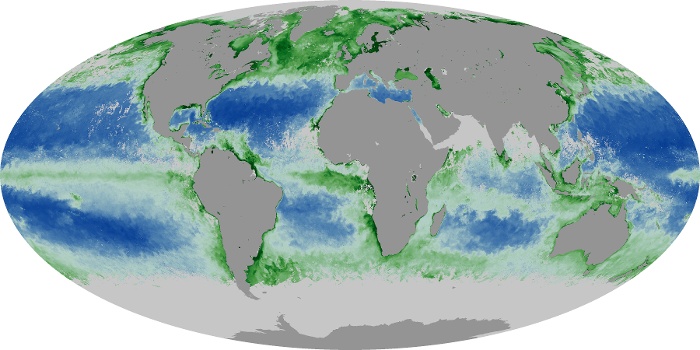

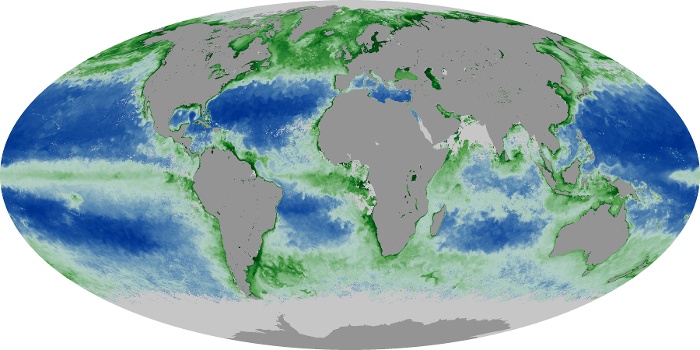

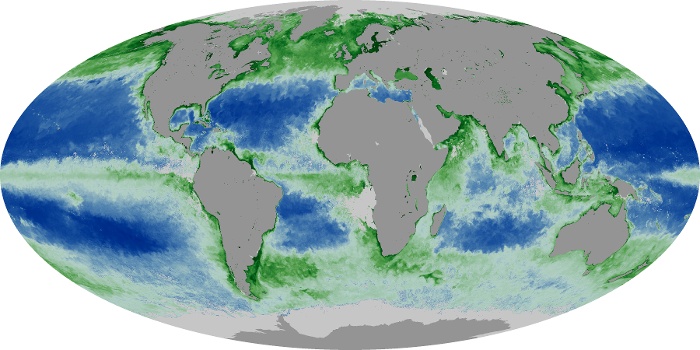

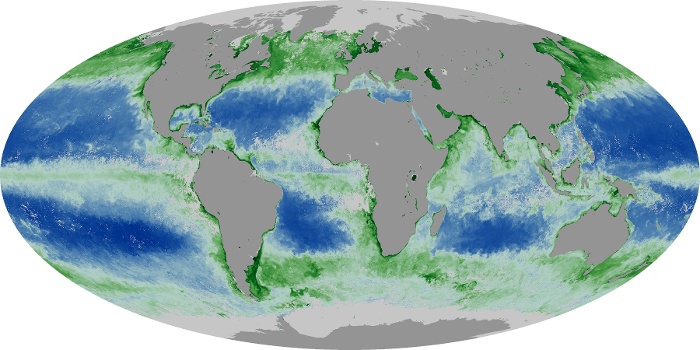

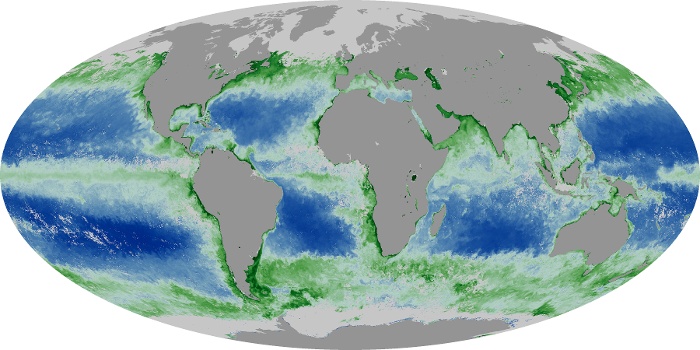

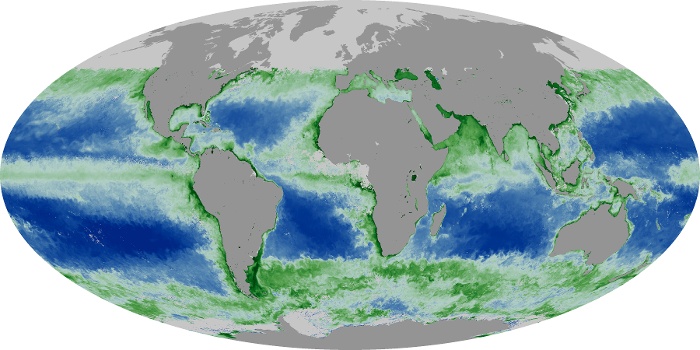

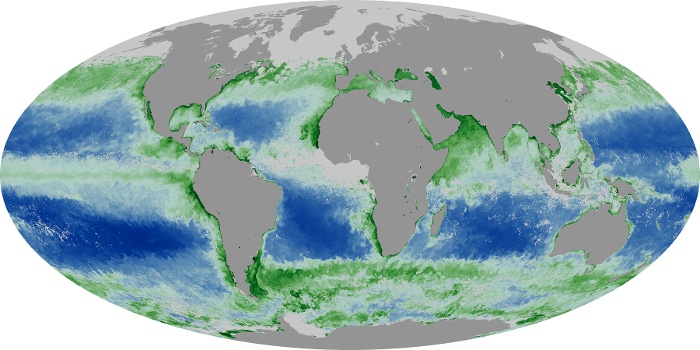

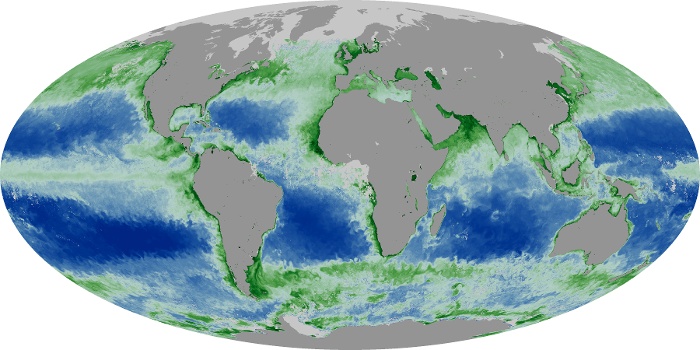

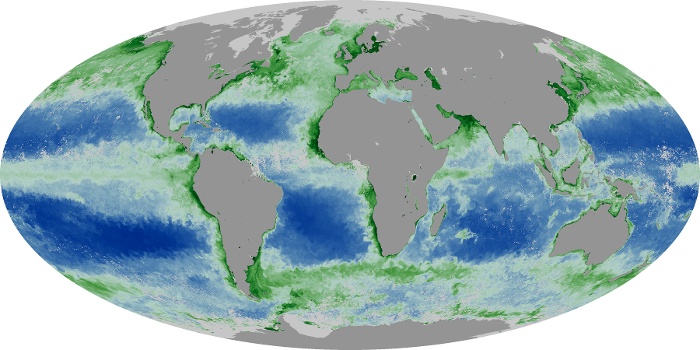

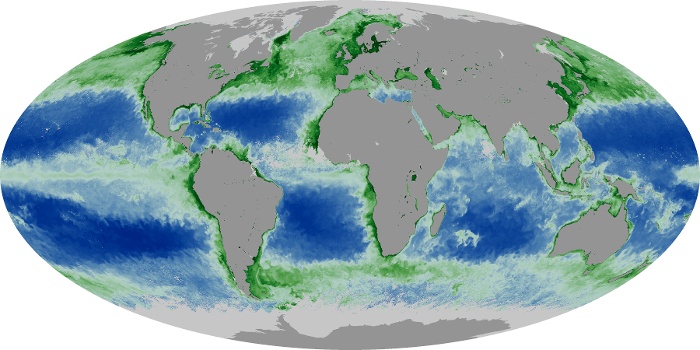

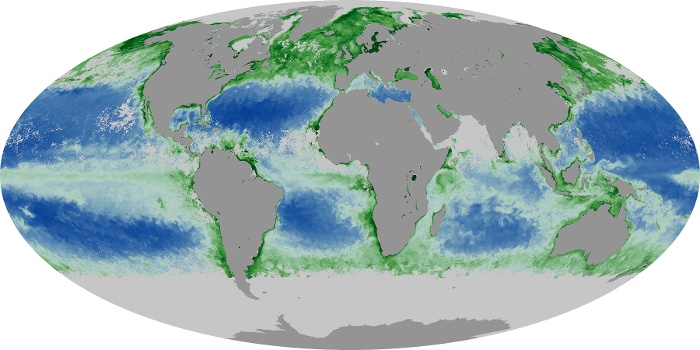

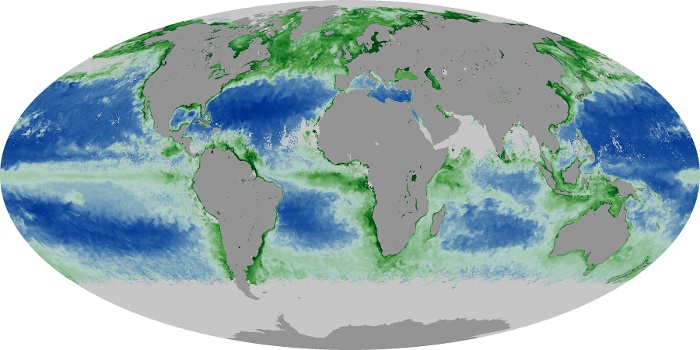

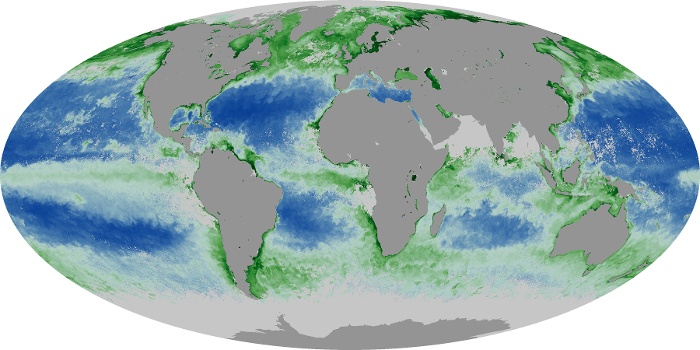

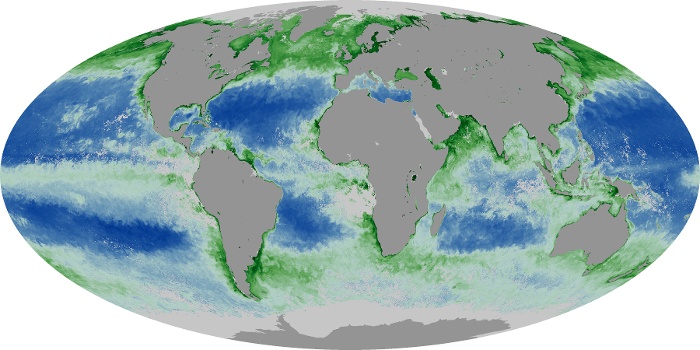

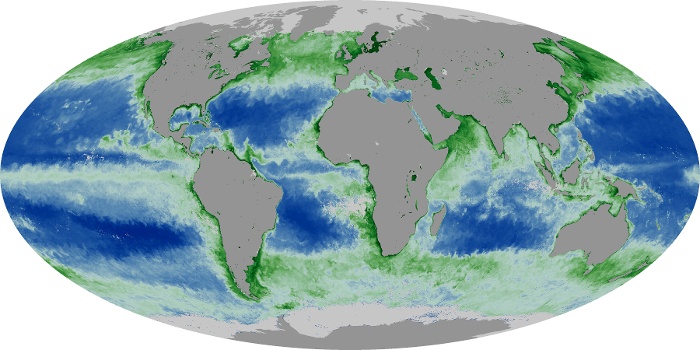

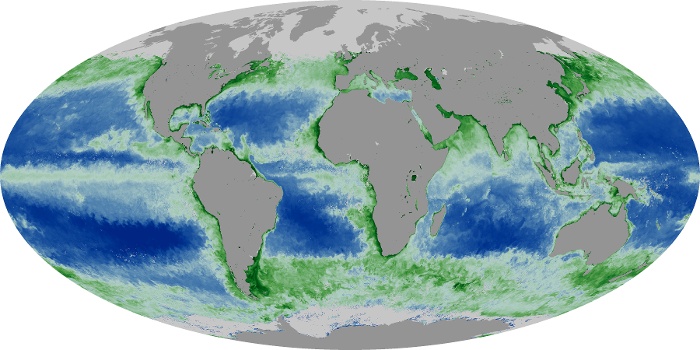

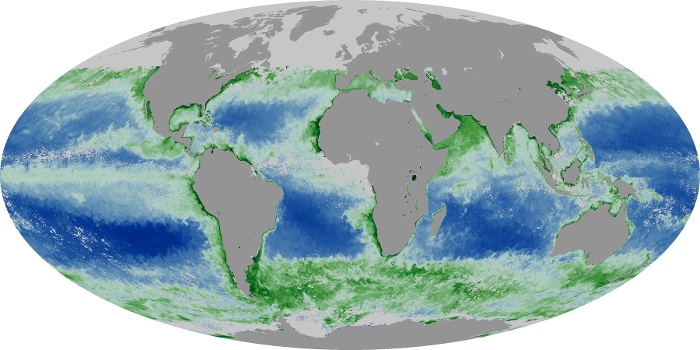

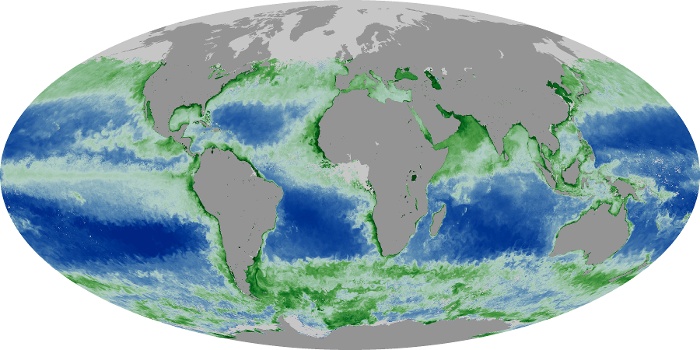

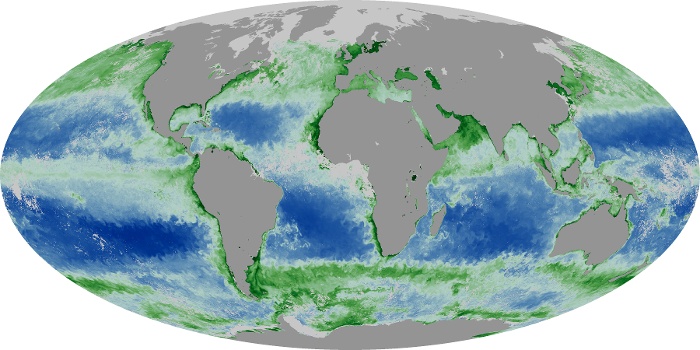

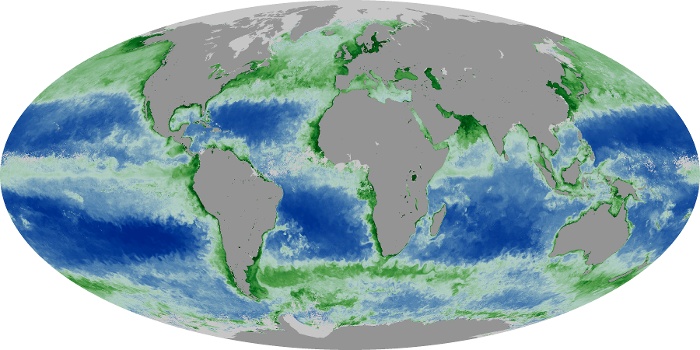

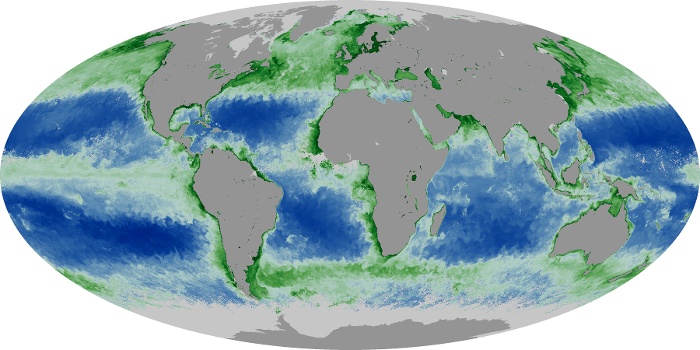

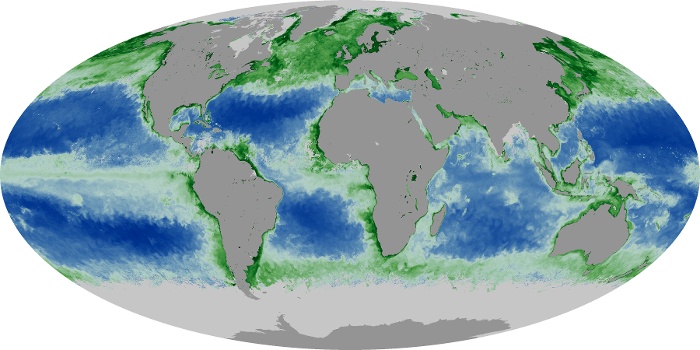

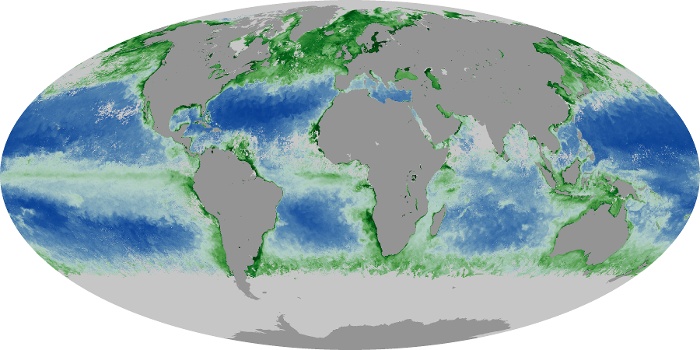

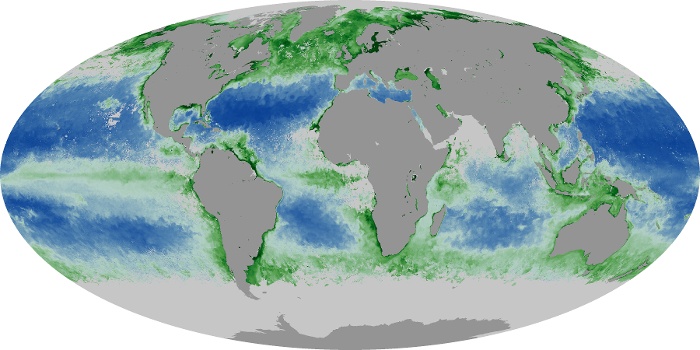

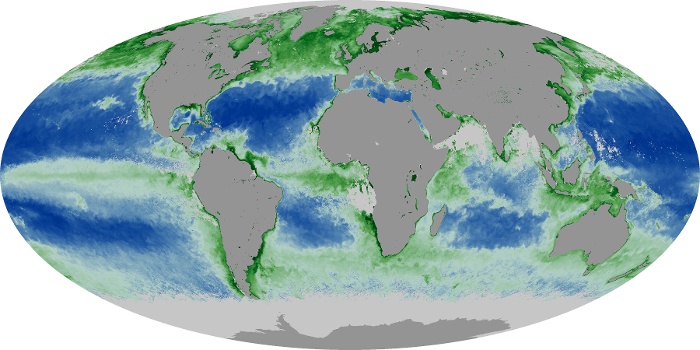

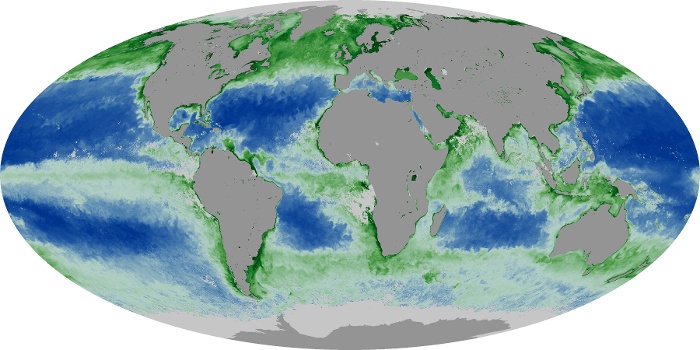

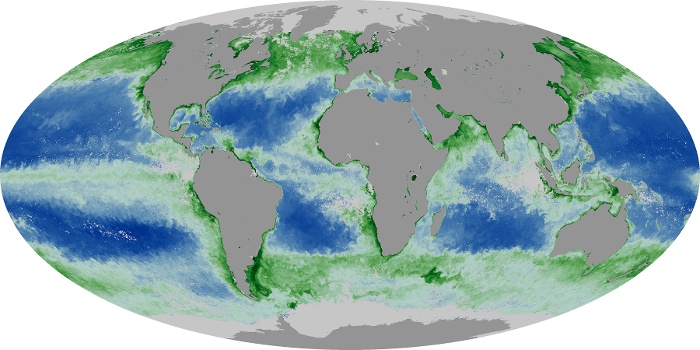

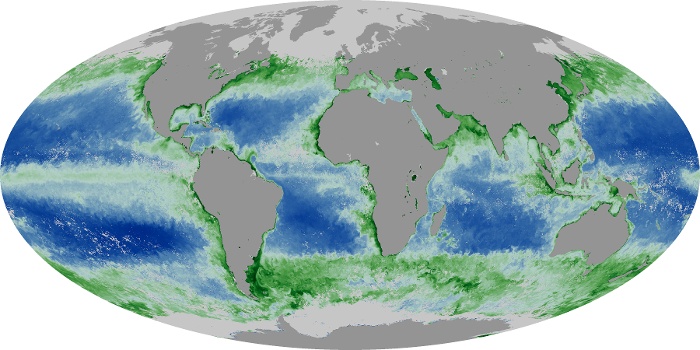

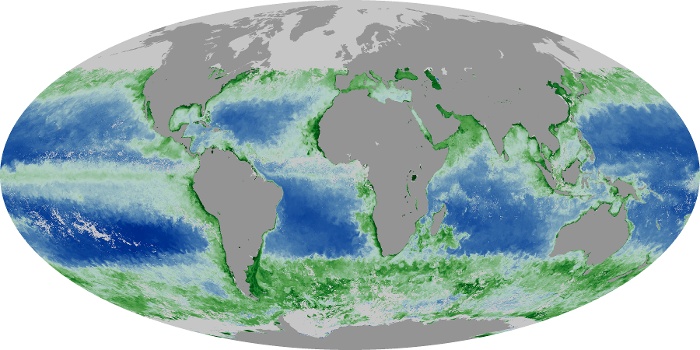

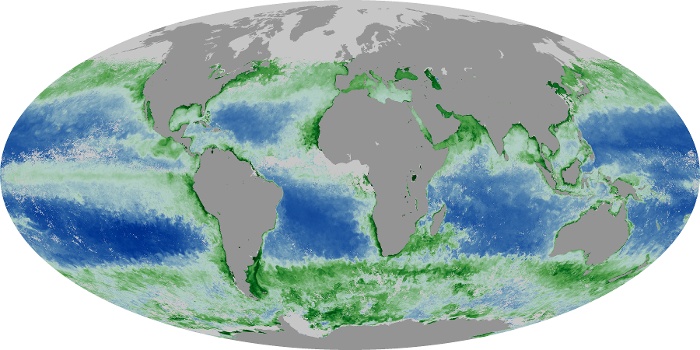

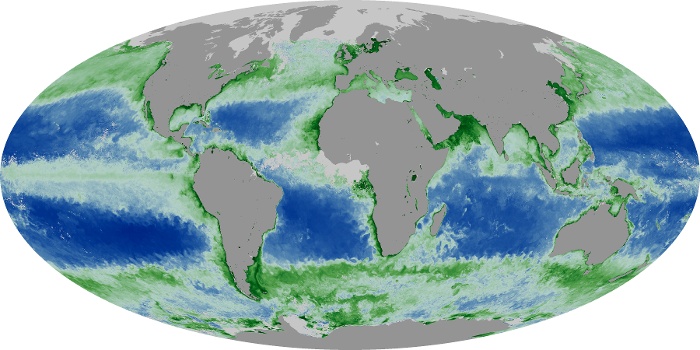

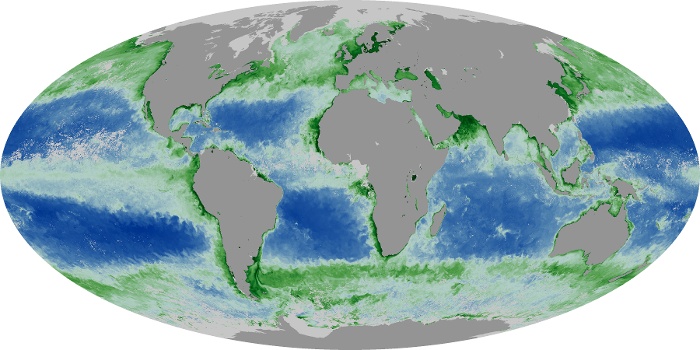

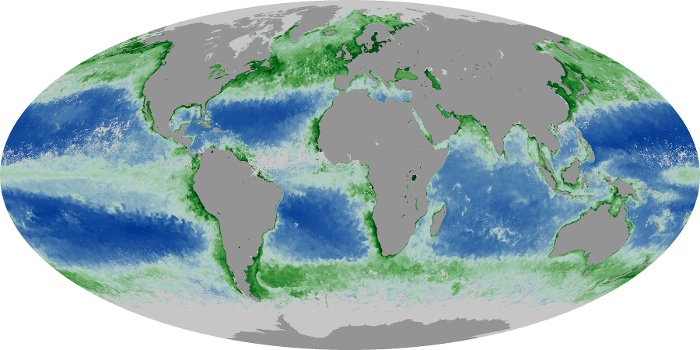

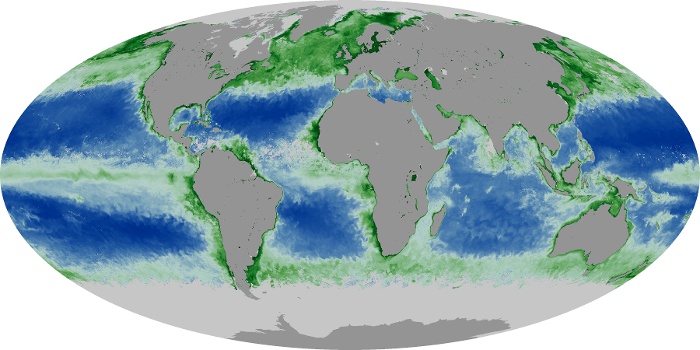

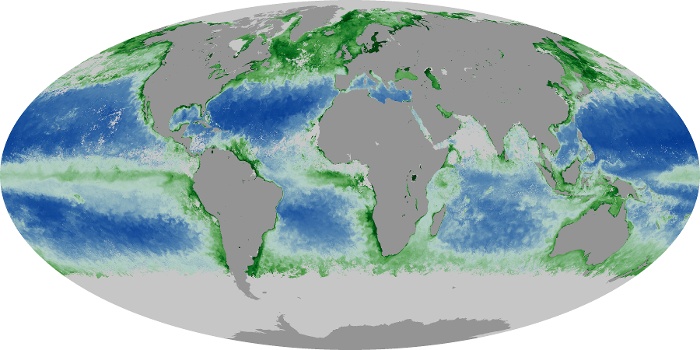

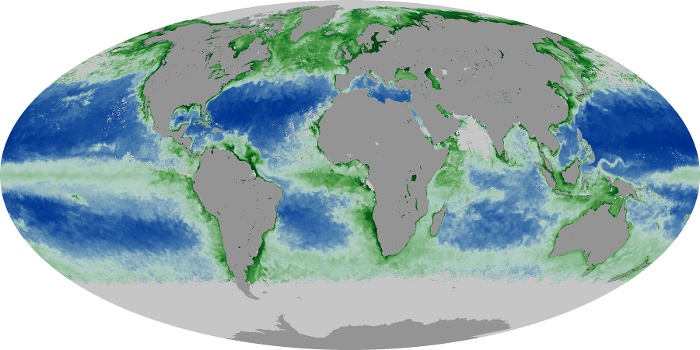

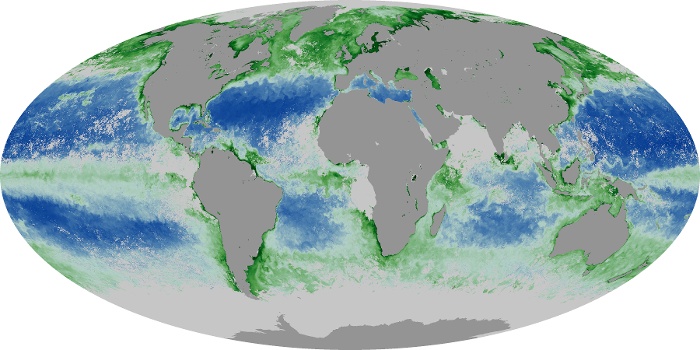

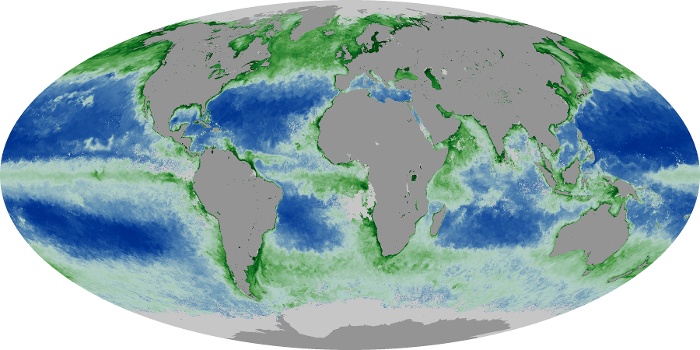

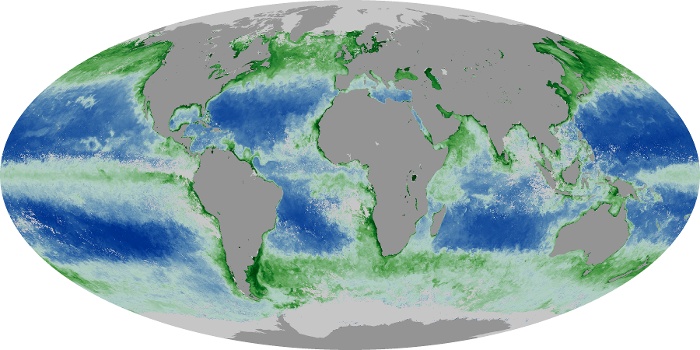

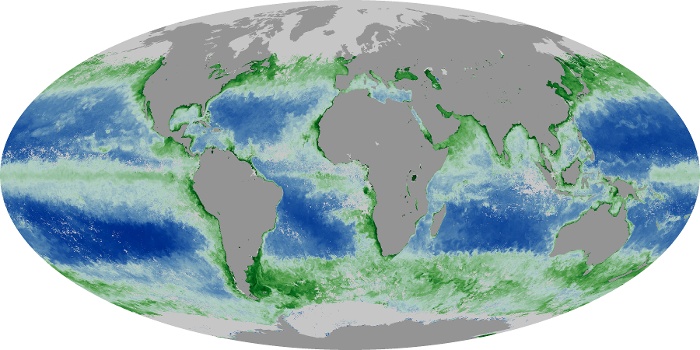

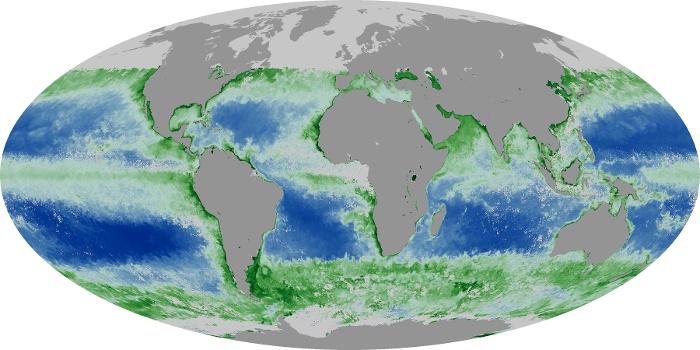

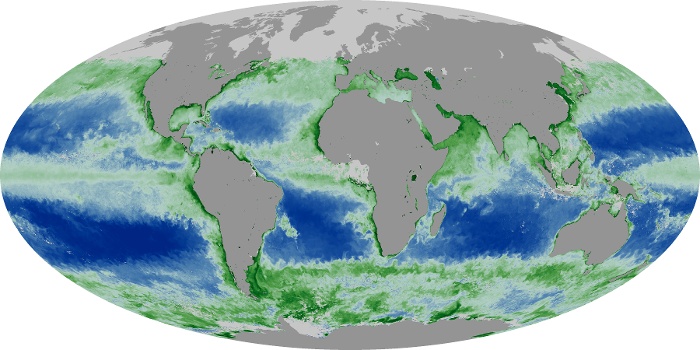

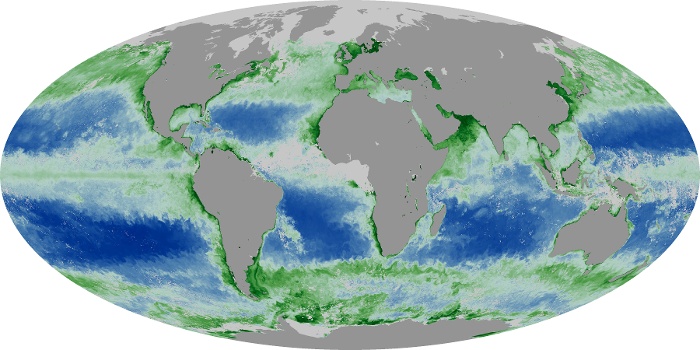

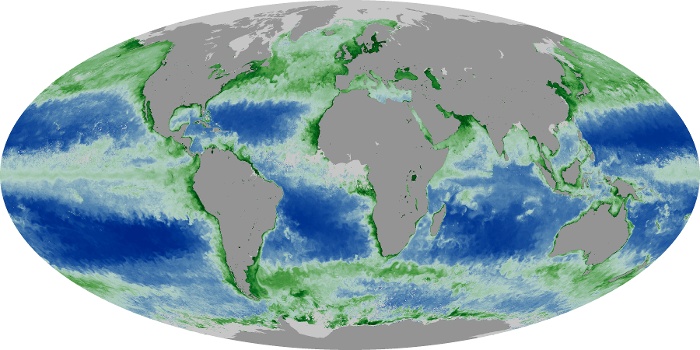

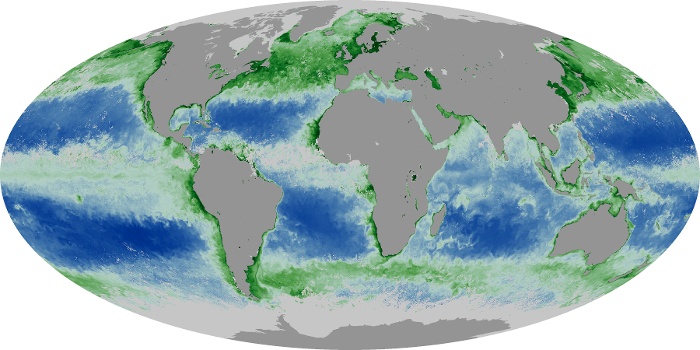

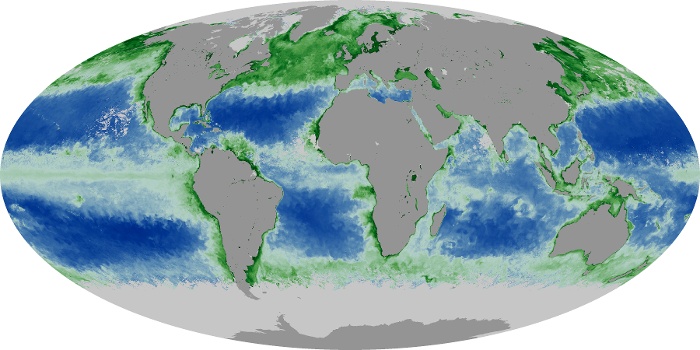

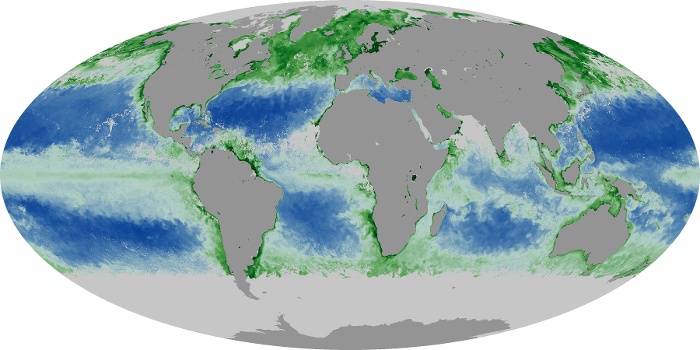

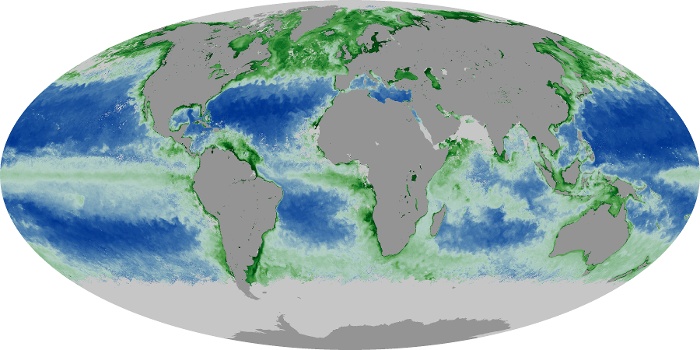

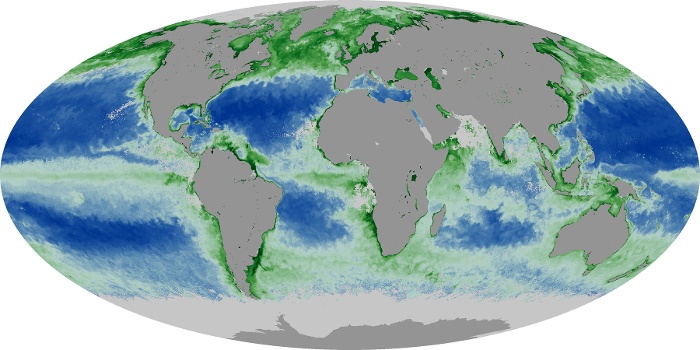

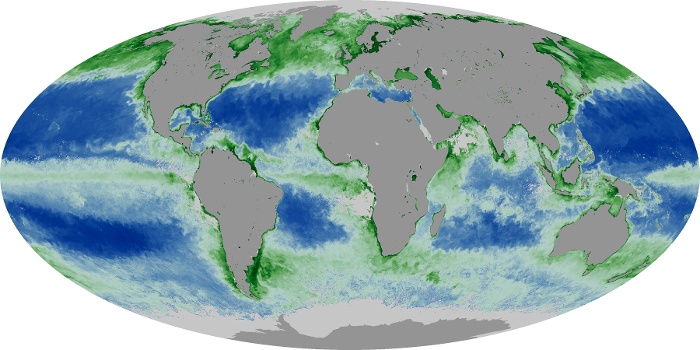

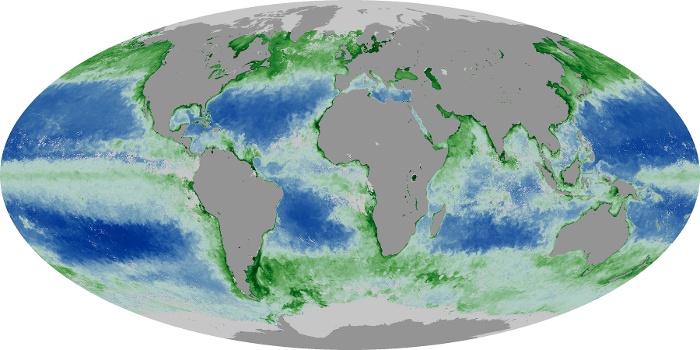

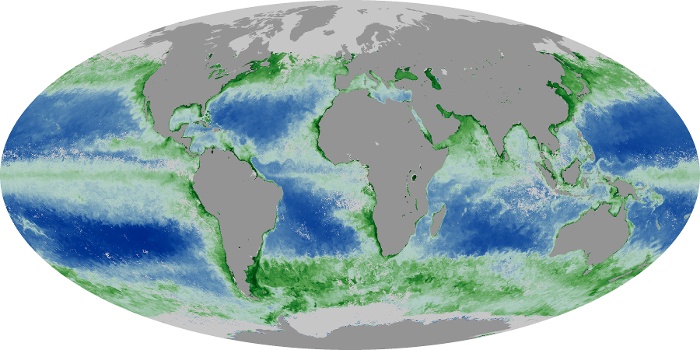

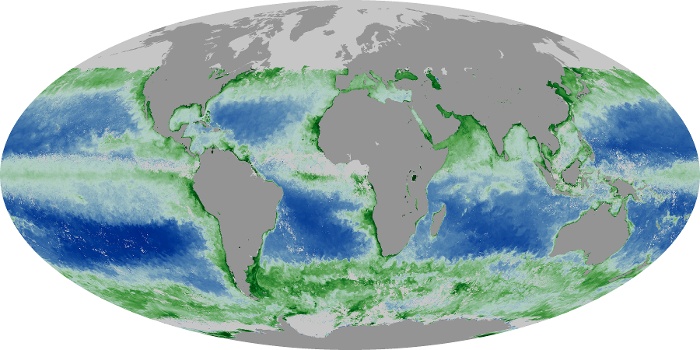

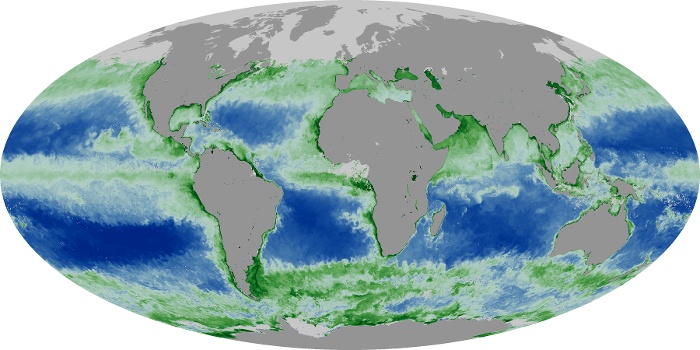

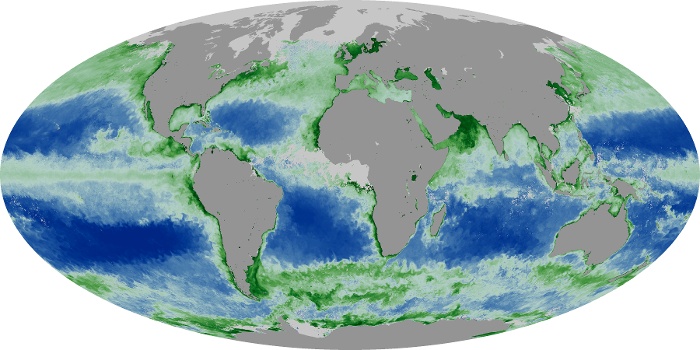

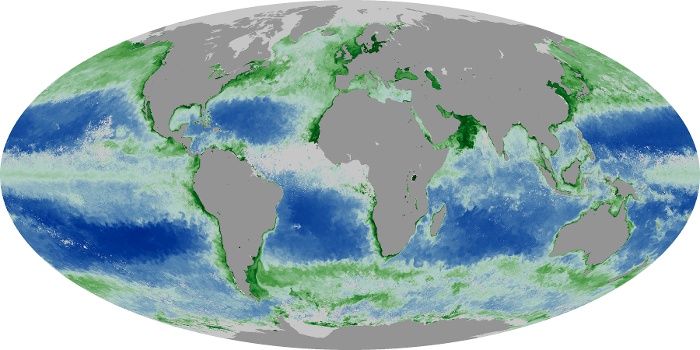

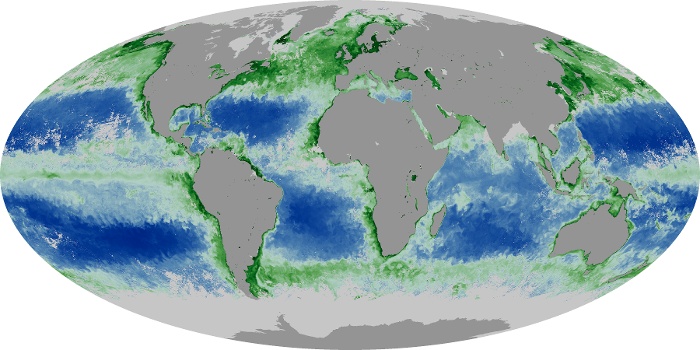

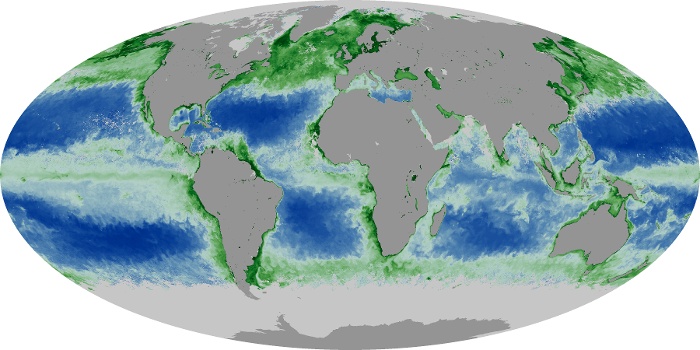

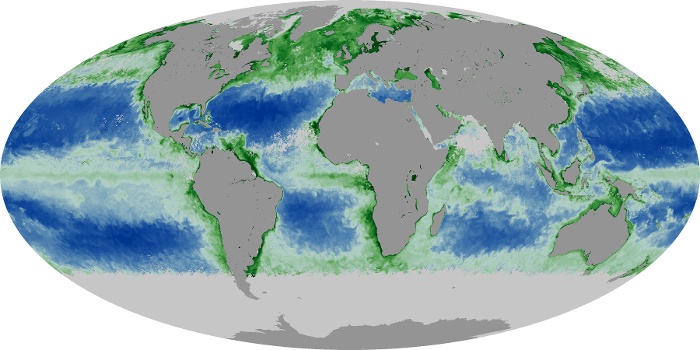

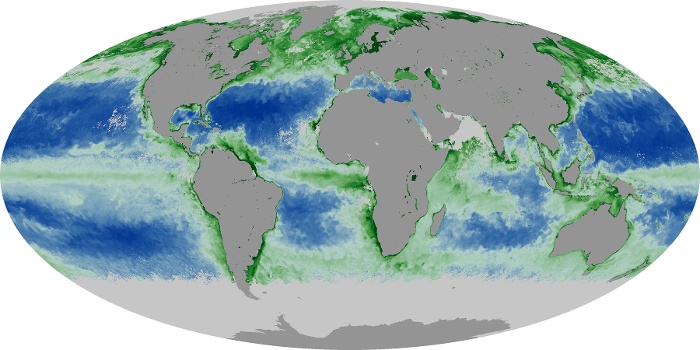

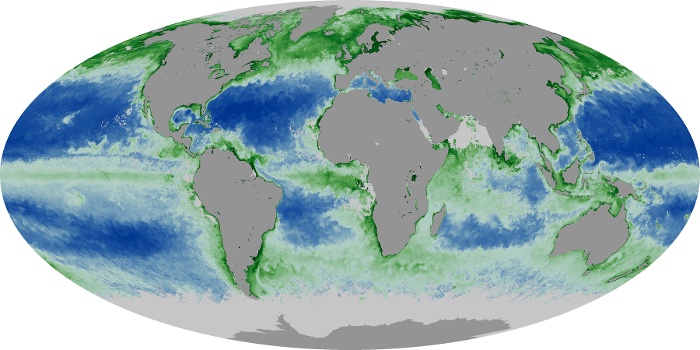

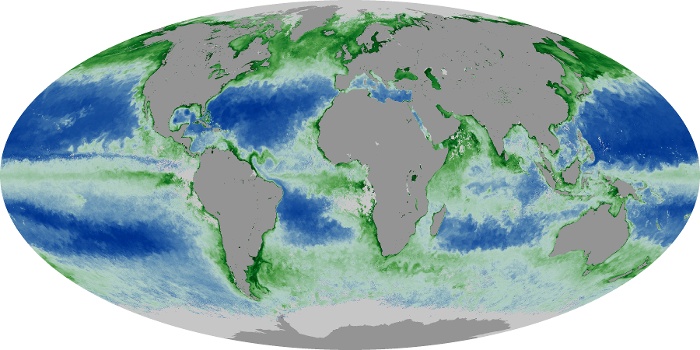

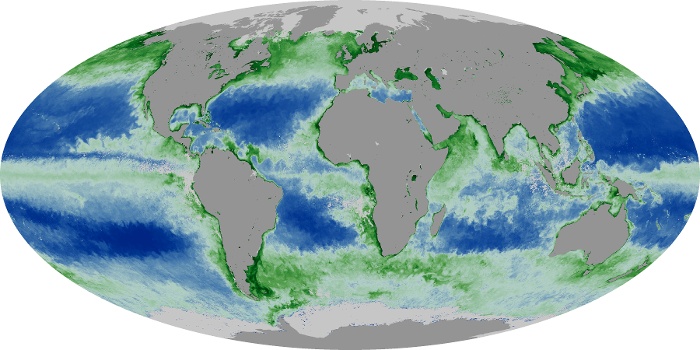

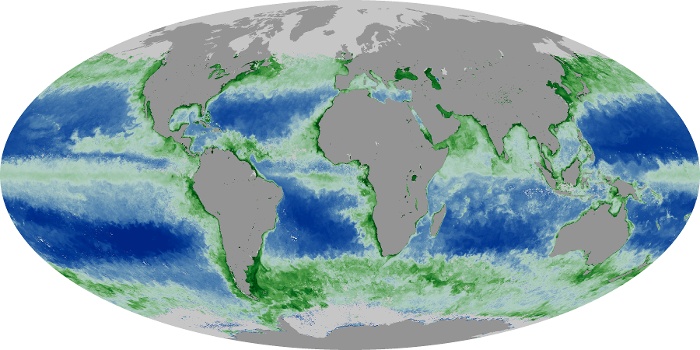

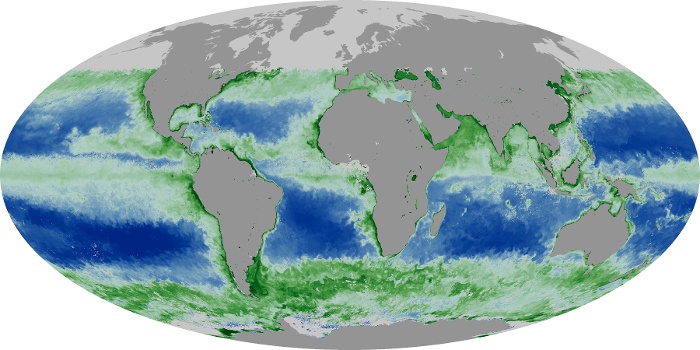

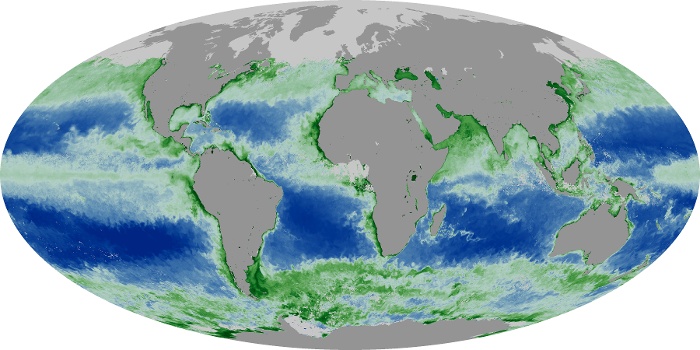

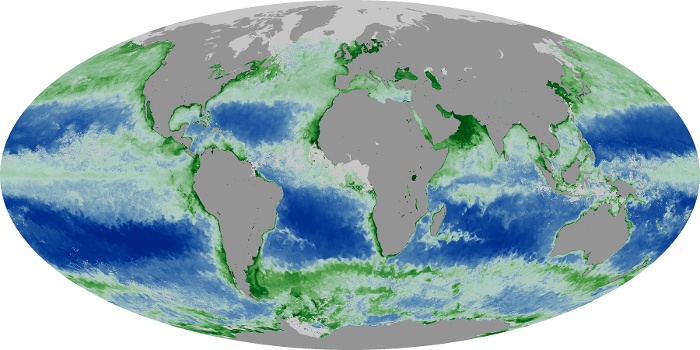

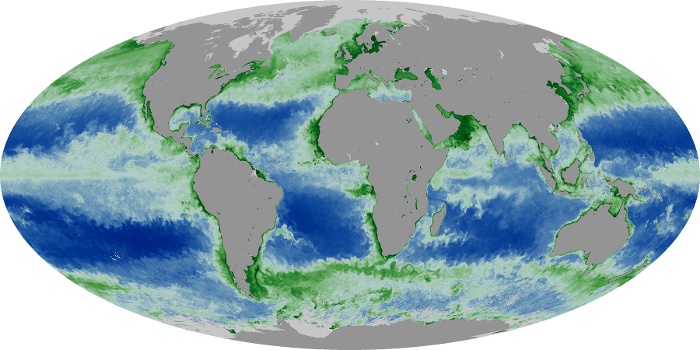

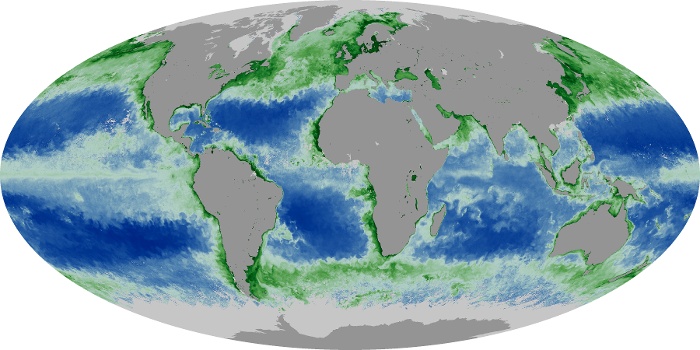

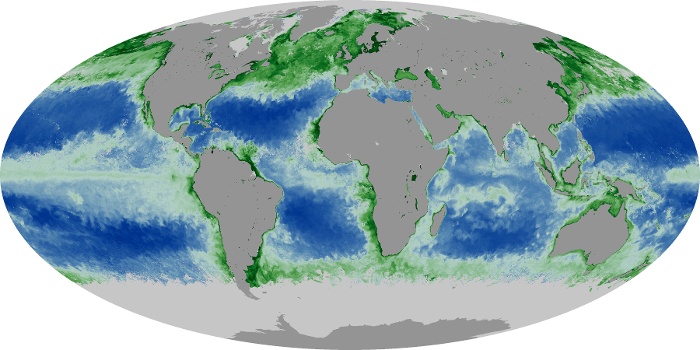

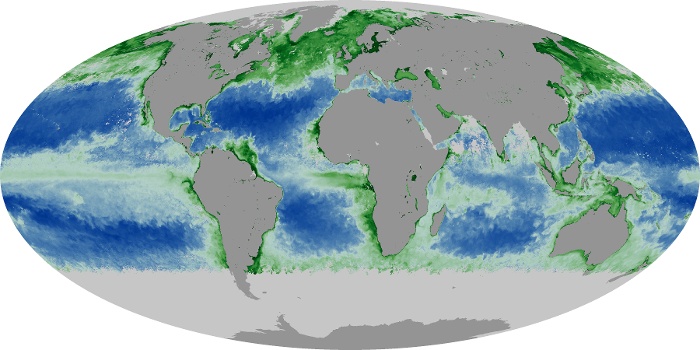

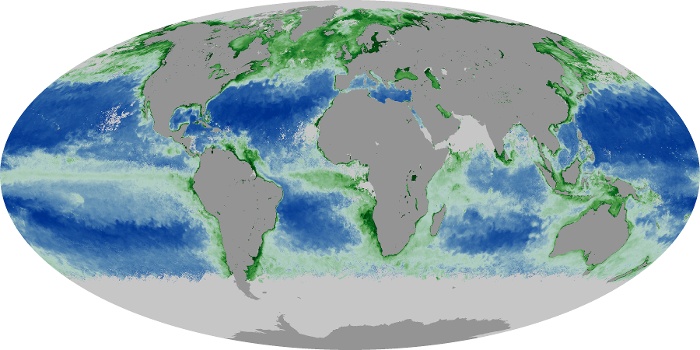

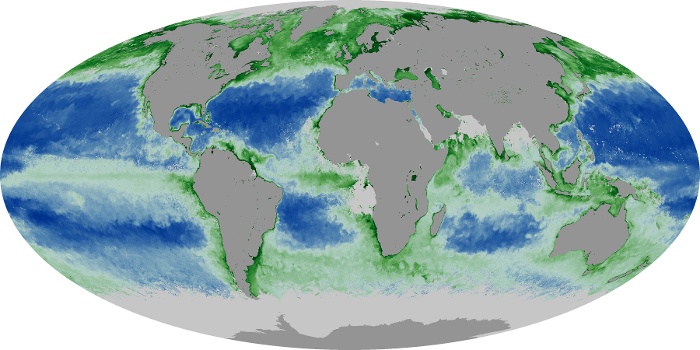

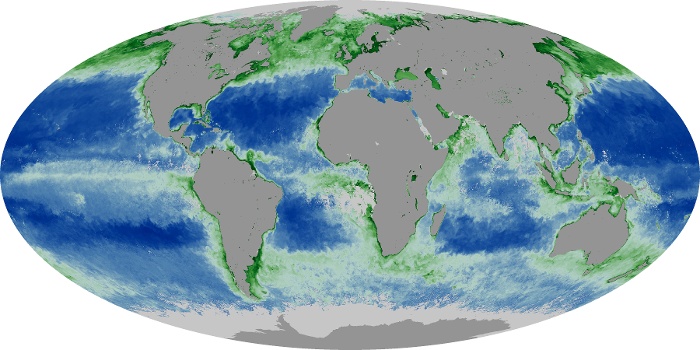

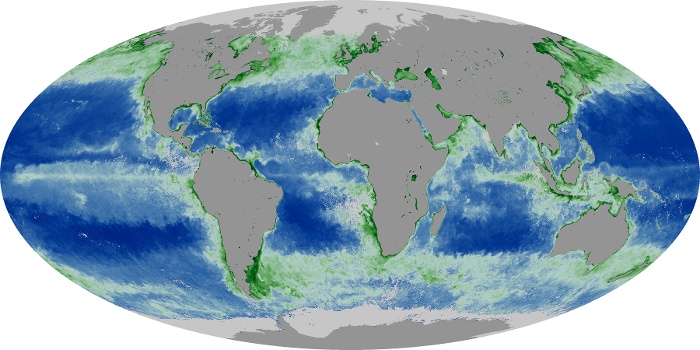

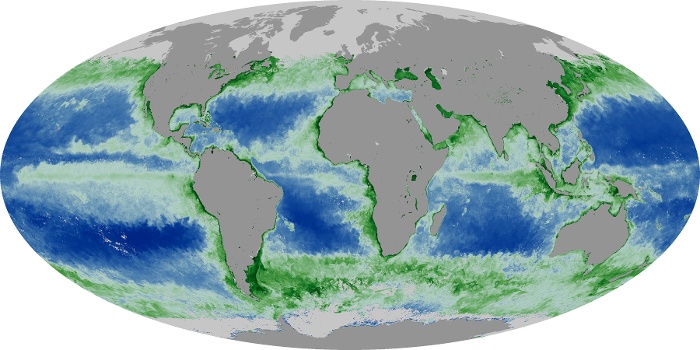

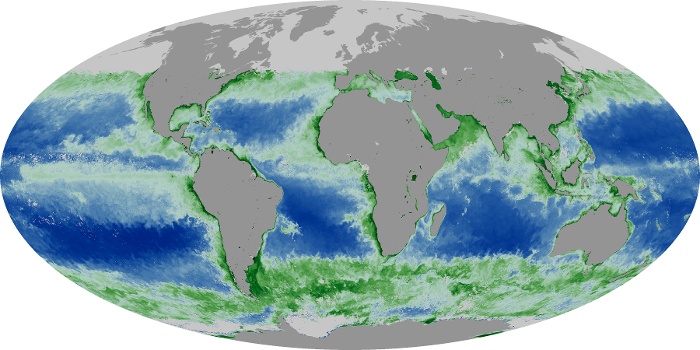

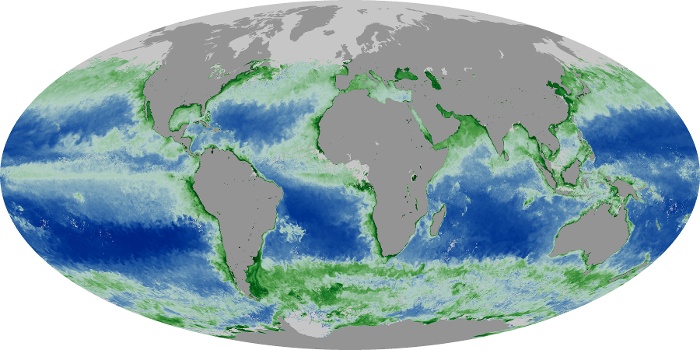

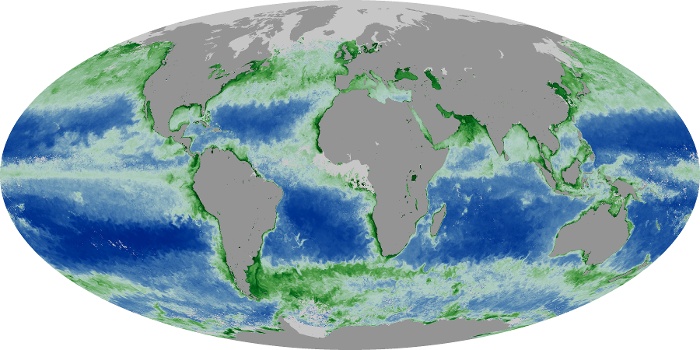

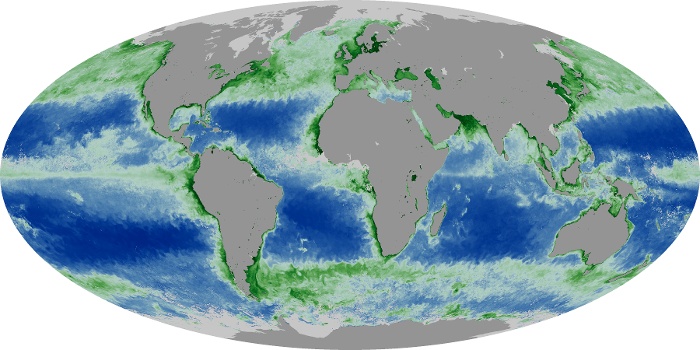

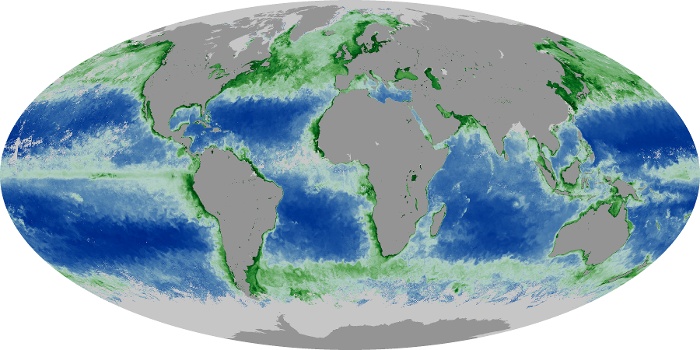

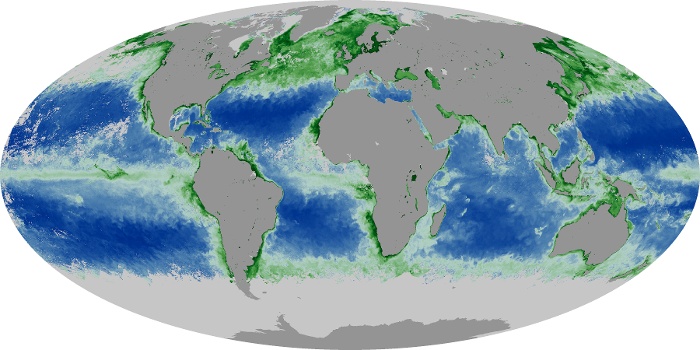

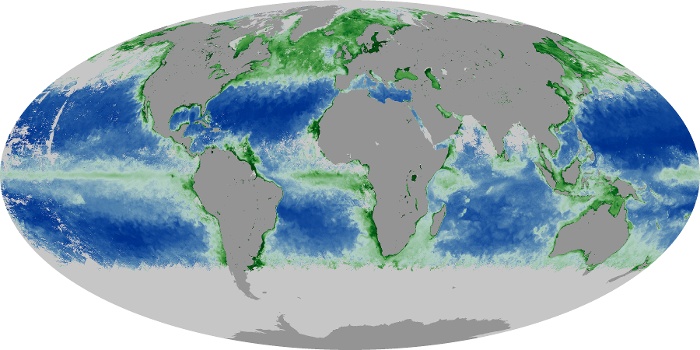

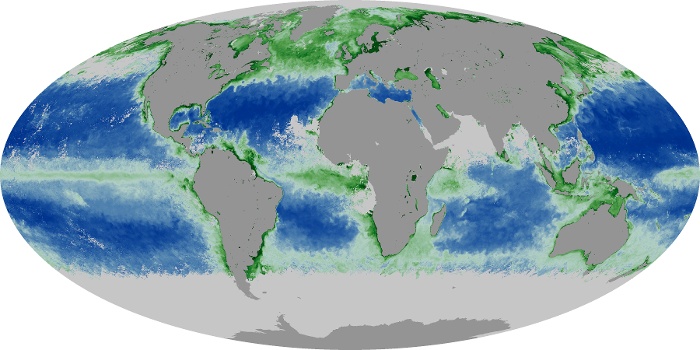

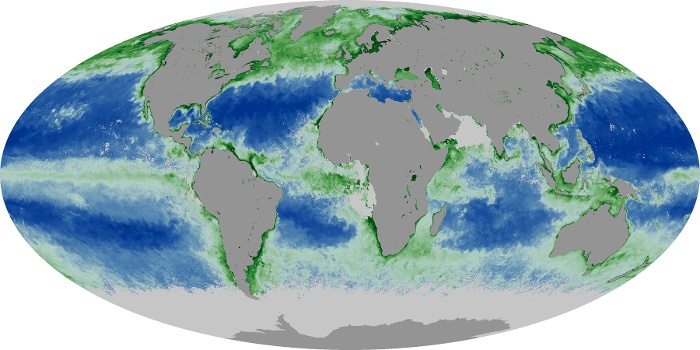

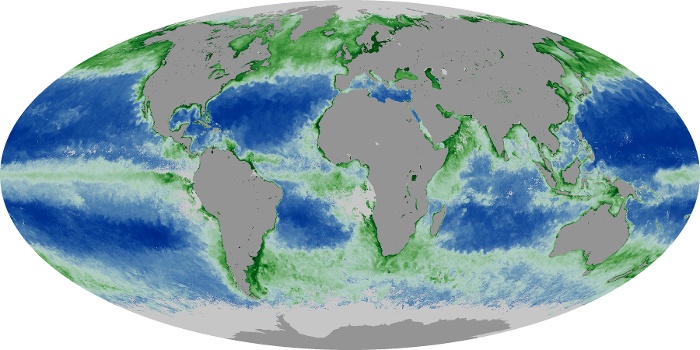

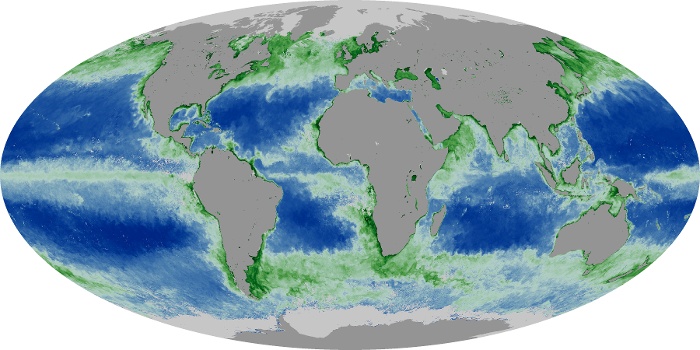

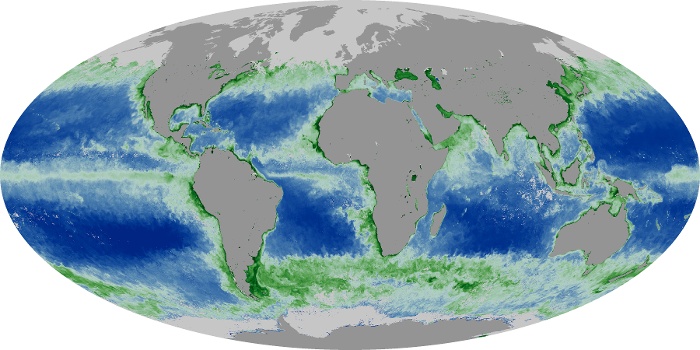

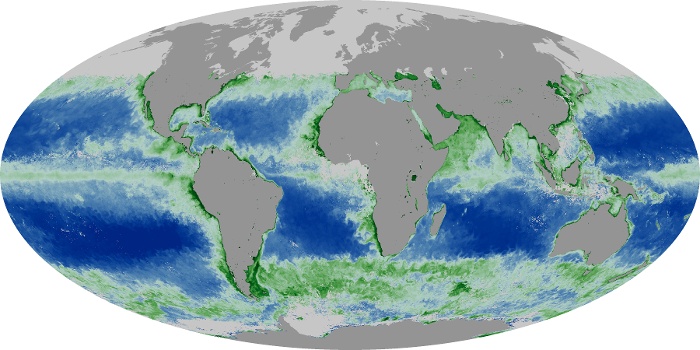

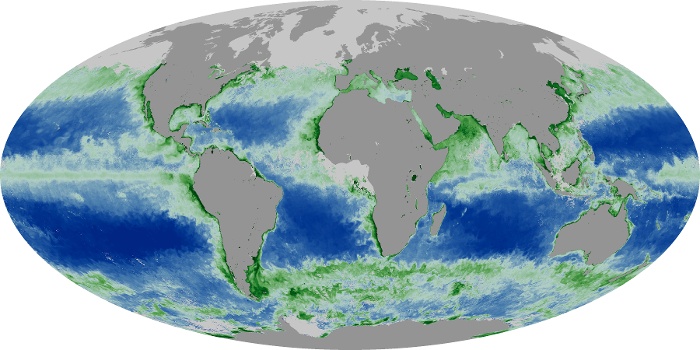

These chlorophyll maps show milligrams of chlorophyll per cubic meter of seawater each month. Places where chlorophyll amounts were very low, indicating very low numbers of phytoplankton are blue. Places where chlorophyll concentrations were high, meaning many phytoplankton were growing, are dark green. The observations come from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Aqua satellite. Land is dark gray, and places where MODIS could not collect data because of sea ice, polar darkness, or clouds are light gray.

The highest chlorophyll concentrations, where tiny surface-dwelling ocean plants are thriving, are in cold polar waters or in places where ocean currents bring cold water to the surface, such as around the equator and along the shores of continents. It is not the cold water itself that stimulates the phytoplankton. Instead, the cool temperatures are often a sign that the water has welled up to the surface from deeper in the ocean, carrying nutrients that have built up over time. In polar waters, nutrients accumulate in surface waters during the dark winter months when plants can't grow. When sunlight returns in the spring and summer, the plants flourish in high concentrations.

A band of cool, plant-rich waters circles the globe at the Equator, with the strongest signal in the Atlantic Ocean and the open waters of the Pacific Ocean. This zone of enhanced phytoplankton growth comes from the frequent upwelling of cooler, deeper water as a result of the dominant easterly trade winds blowing across the ocean surface. In many coastal areas, the rising slope of the sea floor pushes cold water from the lowest layers of the ocean to the surface. The rising, or upwelling water carries iron and other nutrients from the ocean floor. Cold coastal upwelling and subsequent phytoplankton growth are most evident along the west coasts of North and South America and southern Africa.

View, download, or analyze more of these data from NASA Earth Observations (NEO):

Chlorophyll

alert message