Editor’s note: today’s caption is the answer to the June puzzler.

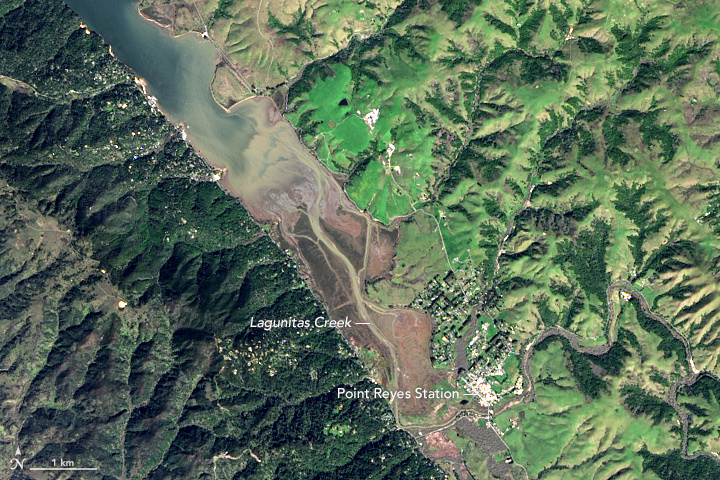

There is an obvious difference between the dark green coniferous forests that dominate the western shore of Tomales Bay and the lighter green grasslands on the east side. But the differences between the two shores run much deeper than the vegetation.

Tomales Bay lies about 50 kilometers (30 miles) northwest of San Francisco, along the edges of two tectonic plates that are grinding past each other. The boundary between them is the San Andreas Fault, the famous rift that partitions California for hundreds of miles.

The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 captured this natural-color image of part of Tomales Bay on March 1, 2017. Lagunitas Creek, a northward-flowing stream that offers critical habitat for the endangered coho salmon, roughly traces the fault.

To the west of the Bay is the Pacific plate; to the east is the North American plate. The rock on the western shore of the Bay is granite, an igneous rock that formed underground when molten material slowly cooled over time. On the opposite shore, the land is a mix of several types of marine sedimentary rocks. In Assembling California, John McPhee calls that side “a boneyard of exotica,” a mixture of rock of “such widespread provenance that it is quite literally a collection from the entire Pacific basin, or even half of the surface of the planet.”

As the plates shift, the ground west of the San Andreas Fault moves northward. On average, movement along the fault averages about 3 to 5 centimeters (1 to 2 inches) per year—about the speed that fingernails grow. However, that movement is anything but steady. The two plates tend to lock together until extreme amounts of pressure build up. When the pressure reaches a breaking point, an earthquake sends the plates lurching. During the Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, a road at the head of Tomales Bay was offset by nearly 6 meters (21 feet).

In the second image, you can see that the direction of the fault follows the orientation of Tomales Bay, running from the head of the Bay through Olema Valley toward Bolinas Lagoon.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Adam Voiland.