If you ever have an urge to hike—or even bathe—inside a volcano, you may want to visit Torfajökull. While this volcano has not had a large eruption since 1477, its 18-kilometer by 12-kilometer caldera is home to one of Iceland’s largest geothermal areas—an exotic landscape dotted with steaming sulfur and mud pools, hot springs, and gas vents.

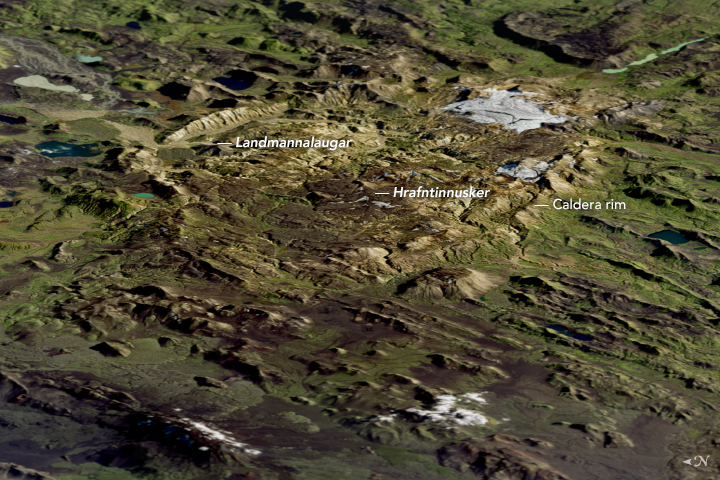

The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 acquired this image of Torfajökull’s caldera on Sep 20, 2014. Calderas, large circular volcanic depressions, form in the wake of major eruptions when the land surface slumps down into an empty or partially empty magma chamber. In Torfajökull’s case, geologists think the caldera formed in stages, with the first collapse happening about 600,000 years ago.

Most of the light gray, brown, and pink domes and ridges within the caldera are the product of lava flows. Torfajökull is notable among Iceland’s volcanoes for discharging relatively rare rhyolitic lava, which is rich in silica. The high silica content gives the resulting rock its light color. (In contrast, silica-poor mafic lavas produce dark rocks.)

Thick ice covered Torfajökull when many of its past eruptions occurred, meaning it was a subglacial volcano. When such volcanoes erupt, they usually generate enough heat to melt the overlying ice and form lakes that immediately quench and cool emerging lava. This creates conditions similar to those found at underwater volcanoes and produces distinctive rock formations. The presence of flat-topped features known as tuyas are one such feature. Likewise, the many domes and ridges made of hyaloclastite—a rock type that includes many fragments of volcanic glass—are also signs of Torfajökull’s icy past.

Most of Torfajökull’s fast-retreating ice cap is gone (except for an area on the southeastern rim of the caldera), but the second image highlights two active subglacial volcanoes to the south with plenty of ice remaining—Katla, which is beneath the Mýrdalsjökull ice cap, and Eyjafjallajökull.

While geothermal activity can be found in several parts of the caldera, some of the most concentrated activity is in Hrafntinnusker, a remote area along the popular Laugavegur hiking trail. Fumaroles and warm streams in Hrafntinnusker have melted intricate caves into glacial ice—a rare phenomenon found in few other places in Iceland. On the northern edge of the caldera, the hot springs at Landmannalaugar—with temperatures of 36 to 40 degrees Celsius (99 to 104 degrees Fahrenheit)—are a popular stop for hikers exploring the colorful rhyolite hills nearby.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Mike Taylor and Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and data from NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team. Story by Adam Voiland.