Every so often, a vibrant green color infuses the waters of Lake Maracaibo. Floating vegetation—likely duckweed—was swirling in the Venezuelan lake when the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite flew over in February 2017.

Most of the time, Maracaibo’s waters are stratified into layers, with nutrient-rich, cooler, saltier water at the bottom, and a warmer, fresher layer near the surface. But after heavy rains, the layers can mix and make the lake an ideal habitat for plant growth. This was the case in June 2004, when a downpour led to a massive bloom of duckweed that prompted the Venezuelan government to declare a state of emergency. Cleanup efforts cost the country millions of dollars.

A narrow strait roughly 6 kilometers (4 miles) wide and 40 kilometers (25 miles) long connects the lake to the Gulf of Venezuela and the Caribbean Sea. The influx of saltwater through the strait makes Maracaibo an estuarine lake. This mixing causes the water currents responsible for the concentric swirl pattern, according to Lawrence Kiage, a professor of geoscience at Georgia State University. At times, larger tides and more forceful winds can create stronger currents in the lake.

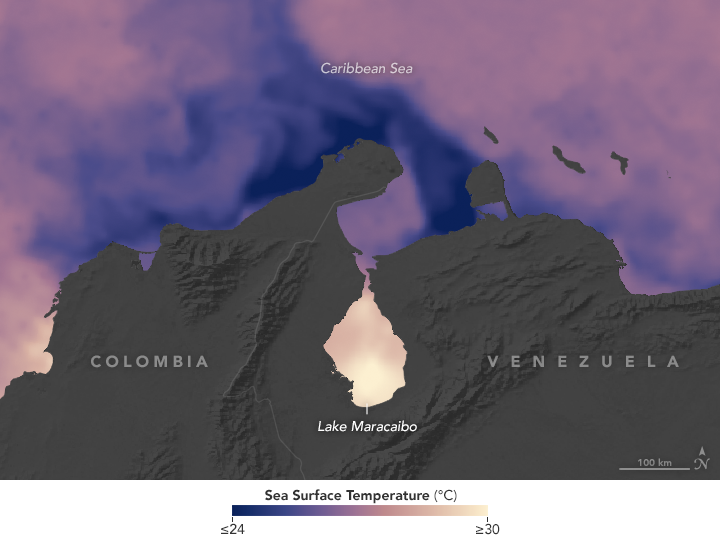

Maracaibo is warm compared to the Caribbean Sea to the north. In the map of sea surface temperatures, warmer water is shown with lighter tones, while darker areas are cooler. The lake is relatively shallow, so sunlight penetrates and warms the surface waters, which hover around 30 degrees Celsius (85° Fahrenheit) throughout the year.

In the natural-color image, notice that the sky above Maracaibo is quite clear, but small tufts of cumulus clouds (sometimes called “popcorn” clouds) dot the surrounding area. Moisture released by forest vegetation through evapotranspiration warms during the day and rises into the atmosphere, where it condenses into clouds. Meanwhile, the air over the lake tends to be colder and drier, hindering cloud formation, said Bastiaan van Diedenhoven, a researcher for Columbia University and NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Popcorn clouds frequently form around rivers in the tropics.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using MODIS data from LANCE/EOSDIS Rapid Response and Sea Surface Temperature data from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory/MUR. Caption by Pola Lem.