The annual Leonid meteor shower will reach its peak this week. But will you be able to see it? You might need to get away from city lights.

About 80 percent of people in the United States live in urban areas. In these areas, the glow of artificial light sources can blot out the wonders of the night sky. City lights make it hard to see anything besides the brightest stars, planets, and celestial phenomena.

For the best viewing, you need to find an area well away from city or street lights. One solution is a dark sky park. In the U.S. and around the world, parks are achieving certification from the International Dark Sky Association (IDA), an organization that calls attention to light pollution. To gain certification, a park must not only meet specific requirements for the quality of observing conditions, but it should also fulfill other obligations such as having a lighting management plan and education programs.

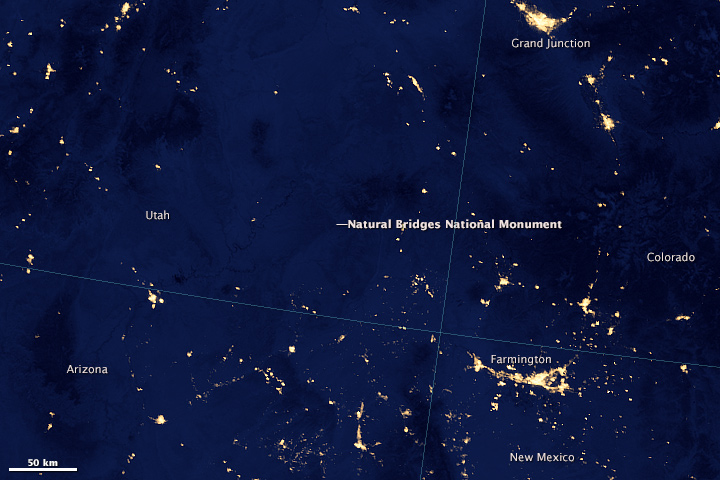

The image of the United States at the top of this page is a nighttime composite assembled from data acquired in 2012 by the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite on the Suomi NPP satellite. The inset boxes show the general location of two IDA gold-tier parks—the highest dark sky designation—where the full array of visible sky phenomena can be seen with the naked eye.

"It's important to point out that these places aren't "dark." They are naturally lit by celestial sources. You can walk in a field in starlight, and through the woods in moonlight," said Christopher Kyba, a postdoctoral scholar at the German Research Center for Geoscience and a member of the IDA board of directors. "The difference is that the city lights are way brighter than natural light, and that's the problem."

Not only does artificial lighting diminish the dark sky resource for stargazers, but studies have shown that light pollution can also affect ecology—from the nesting of sea turtles to the movement of phytoplankton.

The inset box and the second image show Cherry Springs State Park nestled between brightly lit cities of the eastern U.S. The low level of light pollution at Cherry Springs is due in part to its remote location atop a 700-meter (2,300-foot) peak in the Allegheny Mountains. The park is mostly surrounded by undeveloped state forest, and the closest city is about 100 kilometers (60 miles) away. The park's infrastructure and lighting are carefully planned to maximize dark sky recreation. The Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources calls the site "one of the best places on the eastern seaboard for stargazing and the science of astronomy."

The western U.S. also has brightly lit cities, but vast expanses of darkness are more common. The third image pinpoints the location of Utah's Natural Bridges National Monument, a national park that in 2007 was the first area to be designated an IDA dark sky park. According to the National Park Service, Natural Bridges has one of the darkest skies in the country. In some areas of the darkest national parks, visitors can see up to 15,000 stars in a night compared to less than 500 in some urban environments.

Europe also has a network of bright city lights, as shown in the fourth image. The box denotes the region of Hungary detailed in the fifth image. Hortobágyi (Hortobágy) National Park, located about 150 kilometers (90 miles) from Budapest, is a UNESCO World Heritage site known for vast plains and wetlands. It is also an IDA silver-tier park, where brighter sky phenomena are regularly visible, and fainter ones are sometimes visible. The Milky Way, for example, must be visible in summer and winter.

"We will probably always light our cities, but there's no reason we have to do it with the amount of light that we currently use or in the way that we currently light," Kyba said. "Well-lit and brightly lit are not the same thing. Better design could improve visibility in cities while greatly reducing the amount of waste light shone into the sky."

Whether the fainter nighttime phenomena will ever be visible again from urban areas remains to be seen. For example, the effect of the transition toward light-emitting diodes (LEDs) as light sources is unknown. On one hand, LEDs direct light well; less stray light would make the skies darker. But these lights emit a lot of blue light, which makes the sky brighter.

"I hope that 50 years from now we will have well-lit cities in which the Milky Way is again visible in the suburbs," Kyba said, "and perhaps even from urban parks."

If you can find some dark skies in November, look for the Leonid meteor shower. The Leonids occur every year when Earth moves through the dusty debris left behind by Comet Tempel-Tuttle. The intensity of the shower is cyclic. For example, meteors fell at a rate of thousands per second during a storm in 1966, and at a few thousand per hour in storms from 1998-2002. The 2014 shower is forecast to be a modest event, peaking in the early morning hours of November 17-18 with an estimated 15 meteors per hour.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Robert Simmon and Jesse Allen, using Suomi NPP VIIRS data provided courtesy of Chris Elvidge (NOAA National Geophysical Data Center). Suomi NPP is the result of a partnership between NASA, NOAA, and the Department of Defense. Caption by Kathryn Hansen.