Boll weevils—small gray beetles with long snouts—first crossed the Rio Grande River and entered the United States in the 1890s. They rapidly spread throughout the U.S. Southeast and into parts of the Mid-Atlantic, Southwest, and West, devastating cotton crops and causing billions of dollars of damage. In the early 1970s, about one-third of all pesticides applied in the United States targeted boll weevils. In recent years, boll weevil eradication teams have brought a powerful new tool to the fight—satellite data.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service launched a national campaign to eradicate the pest in the late 1970s—an effort that has involved deploying pheromone-based traps to identify infestations, spraying infested crops with insecticides, and encouraging farmers to manage cotton carefully. (Planting early, harvesting promptly, and removing old stalks or volunteer cotton plants quickly makes it harder for boll weevils to reproduce.) Due to the campaign, boll weevils are now on the verge of eradication in the United States. Ninety-seven percent of U.S. cotton fields are now free of the pest.

But the insect remains a persistent problem in the Rio Grande Valley in southern Texas, where it is warm and humid enough for the beetles to easily survive the winter. Also, new beetles periodically arrive from Mexico, where populations persist despite declining significantly in recent years. To help fight the problem, boll weevil eradication specialists need to know where cotton fields are located early in the growing season—a task that is complicated by the fact that farmers rotate between cotton and other crops and typically don't report cotton field locations to state authorities until later in the growing season.

That’s where satellite data can help. The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 and the Operational Land Imager-2 (OLI-2) on Landsat 9 collect new images of the Rio Grande Valley every eight days, and the sensors make observations with enough detail that trained experts—and well-trained computer algorithms—can distinguish between cotton, sorghum, and other crops.

In the Landsat image at the top of the page, which is centered on Willacy and Cameron counties, the lighter green fields are cotton. In Texas, cotton is planted in February through March and harvested in August through September. The image was acquired on May 13, 2022, during the early part of the growing season. The darker green fields are mostly sorgham or corn. These two counties are the top cotton-producing counties in the Rio Grande Valley.

“Landsat data is crucial because it tells us early in the season where farmers are growing cotton,” said Patrick Burson, the chief operating officer at the Texas Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation. “And that allows us to start control efforts early and stop infestations before they become severe and spread.”

Chenghai Yang, a research agricultural engineer at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Southern Plains Agricultural Research Center in College Station, explained how the technique works. “With Landsat and the European Sentinel-2 satellites, we can use visible and near-infrared observations to get a good measure of when and how plants are greening up and building biomass at early growth stages,” Yang said. “We can use that to categorize a given field as cotton or something else.”

The foundation eliminates boll weevil populations by constantly monitoring an area's cotton fields using pheromone-based traps. If any boll weevils are captured in traps, foundation personnel set additional traps, work with farmers to remove any habitat where boll weevils can reproduce, and spray insecticides when necessary.

“We started using Landsat data to locate cotton fields early in the growing season in 2019, and it has worked incredibly well,” said Burson. “It makes us more efficient. It’s part of the reason we have seen the number of boll weevils in the Rio Grande Valley drop to just a few thousand in the past few years.”

Decades ago, the group would regularly trap millions of boll weevils each year. As recently as 2018, they trapped 96,000. In 2022, numbers were in the hundreds for much of the season until one field with an infestation late in the year captured 3,755 boll weevils, according to Burson.

Some boll weevil watchers estimate that the bugs could be gone from the Rio Grande Valley within five years. “But there are lots of factors,” added Burson. “The subtropical environment in the Rio Grande Valley makes eradicating the weevil more difficult than in other areas of the United States. And big weather events like tropical storms can move weevils around and set off infestations in ways that are hard to predict.”

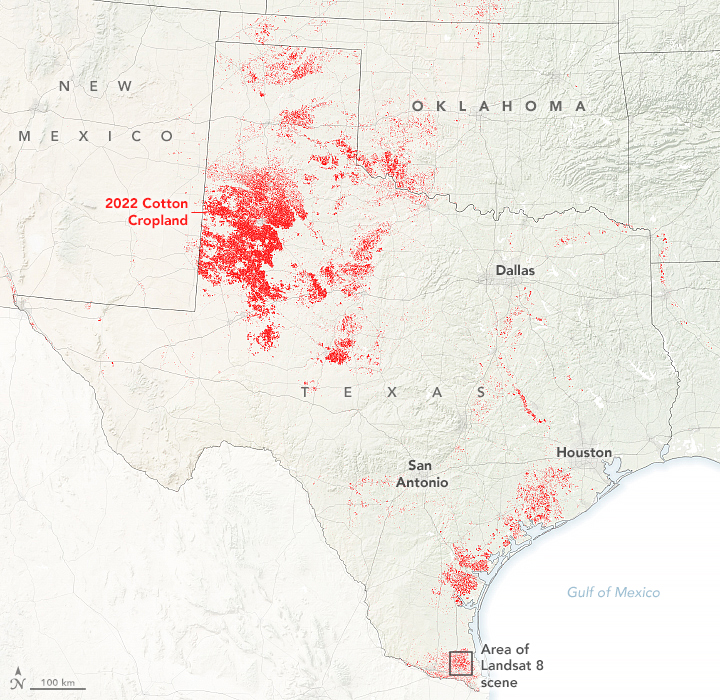

The map above shows cotton-growing areas within Texas (in red) in 2022. The map was built using 2022 the Cropland Data Layer product provided by the National Agricultural Statistics Service, which includes data from the USGS National Land Cover Database and from satellites such as Landsat 8, ResourceSat-2, and Sentinel-2.

U.S. cotton is grown predominantly in 17 states ranging from Virginia to Georgia to Arizona to California. Among U.S. States, Texas is the largest producer, contributing approximately 40 percent of U.S. cotton production. The largest cotton-producing area in Texas is the South Plains, the area in northern Texas along the border with New Mexico. Boll weevils were eliminated from the South Plains around 2008.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and cropland data from USDA NASS. Photograph by Steve Ausmus (USDA/ARS). Story by Adam Voiland.