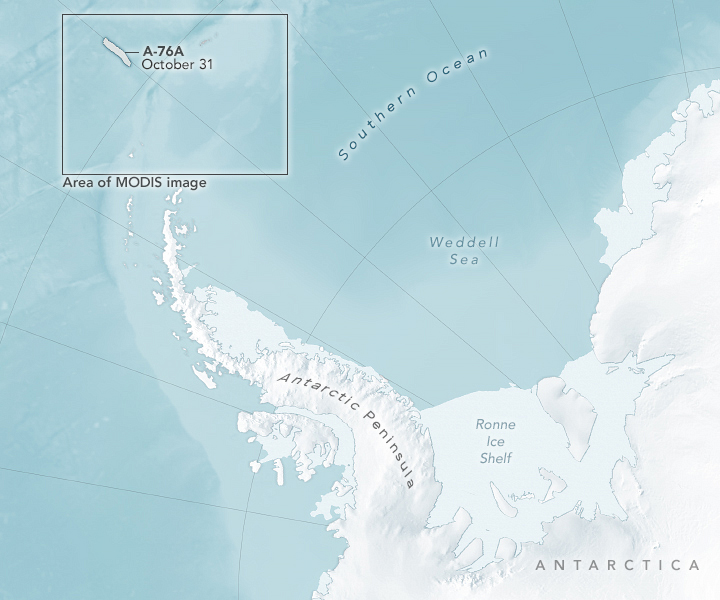

In October 2022, a clearing in the clouds revealed a huge, geometric piece of ice floating in the Drake Passage. This is Antarctic iceberg A-76A—the biggest remaining piece of what was once the largest iceberg floating in the world’s oceans.

The berg is visible in this natural-color image, acquired on October 31, 2022, with the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite. Notice the iceberg’s long tabular shape is distinct from the sea ice farther south in the Southern Ocean. (Icebergs are not sea ice; they are the floating fragments of glaciers or ice shelves, whereas sea ice is frozen seawater that floats on the ocean surface.)

The iceberg’s parent berg (A-76) broke from Antarctica’s Ronne Ice Shelf in May 2021. At the time, it was the largest iceberg anywhere on the planet. Within a month, the iceberg lost that status when it broke into three named pieces. The largest of those pieces—Iceberg A-76A—now drifts nearly 2,000 kilometers (1,200 miles) away in the Drake Passage. The passage is a turbulent body of water between South America’s Cape Horn and Antarctica’s South Shetland Islands, including Elephant Island visible in this image.

Despite the long journey, the iceberg’s size remains remarkably unchanged. In June 2021, the U.S. National Ice Center (USNIC) reported that A-76A measured 135 kilometers long and 26 kilometers wide—a total area equal to about twice the size of London. In October 2022, USNIC reported that the berg maintained the same dimensions.

It remains to be seen where A-76A will drift next. It is already more than 500 kilometers north of its position in July 2022, when the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-1 satellite showed the berg passing the Antarctic Peninsula. Sentinel-1 satellites carry synthetic aperture radar instruments, which can observe surfaces even in the darkness of austral winter.

As they continue to drift north, icebergs are usually pushed east by the powerful Antarctic Circumpolar Current funneling through the Drake Passage. From that point, icebergs often whip north toward the equator and quickly melt in the area’s warmer waters.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Kathryn Hansen.