Following three consecutive failed rainy seasons, more than 20 million people in eastern Africa now face some of the worst food security risks in 35 years. Climate and agriculture experts are advising governments and relief agencies to expect a significant need for food assistance in Somalia, Kenya, and Ethiopia. Climate change and ongoing La Niña conditions in the Pacific Ocean, half a world away, have contributed to the persistent dry weather and might bring more of it during the next rainy season.

The warnings come from the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), a program supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). FEWS NET assembles global and regional analyses of food security (particularly conditions for farming and livestock husbandry) to help governments and relief agencies plan for and respond to humanitarian crises. Several U.S agencies support FEWS NET; NASA provides satellite imagery and climate and weather data.

Tropical countries within the Horn of Africa tend to have two rainy seasons: the gu in March, April, and May, and the deyr in October, November, and December. The 2020 and 2021 deyr seasons were both substantially drier than normal, and the 2021 gu also came up short. Levels of precipitation have been the lowest on record in some areas; the Shabelle-Juba river basins have seen their lowest rainfall totals since 1981. Kenya and Somalia have declared drought emergencies; similar conditions have also prevailed in southern and eastern Ethiopia.

“These back-to-back blows are hard for the farmers to take,” said Ashutosh Limaye, a scientist at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center and a close collaborator with the SERVIR Eastern and Southern Africa Hub (a NASA-USAID collaboration). “We are heading into a dry season, and the seasonal outlook does not look favorable either. The challenge is not just the soil moisture or the rainfall anomalies; it is the resilience of the population to drought.”

In its December 2021 report, FEWS NET declared: “A poor March-May 2022 season would result in an unprecedented (since 1981) sequence of four below-normal rainfall seasons...Even if March-April-May rains are normal, the region will experience lingering long-term rainfall deficits.” Many areas in the Horn of Africa are expected to face “crisis” and “emergency” levels of food insecurity.

The map on the top left shows precipitation anomalies for the 2021 deyr season, or how much rainfall was above or below average for the October through December period. Measurements come from the Climate Hazards Center Infrared Precipitation with Stations (CHIRPS) data set.

The map at the top right shows anomalies in the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), a satellite-derived product used to assess crop conditions. NDVI measures the health, or “greenness,” of vegetation based on how much red and near-infrared light the leaves reflect. Healthy vegetation reflects more infrared light and less visible light than stressed vegetation. The map compares NDVI from December 2021 with the long-term average from 2000 to 2013. The data come from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite and the analysis comes from the USGS FEWS NET Data Portal.

Successive rain shortfalls in eastern Africa have had a cumulative effect: smaller crop harvests; shortages of forage; depleted water supplies; and weakened and depleted livestock herds. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization reported that at least 60,000 animals have been lost to starvation, and milk production is 80 percent below average. Production of cereals during the 2021 deyr was reduced by 50 to 70 percent, while maize and sorghum production were down 15 to 25 percent in 2020 and 50 percent in 2021.

Current soil moisture forecasts from the NASA Hydrologic Analysis and Forecast System (NHyFAS) indicate there could be further reductions in soil moisture in the common months. As the 2021 rainy season draws to a close, hot and dry air conditions and further drying soils, watering holes, and pasturelands.

The dire agricultural conditions have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and by violent regional conflicts. East Africans are simultaneously dealing with rising prices for commodities (locally and globally) and with the loss of income from failed harvests and depleted livestock. And the region still has not fully recovered from the losses of a deep drought in 2016-17.

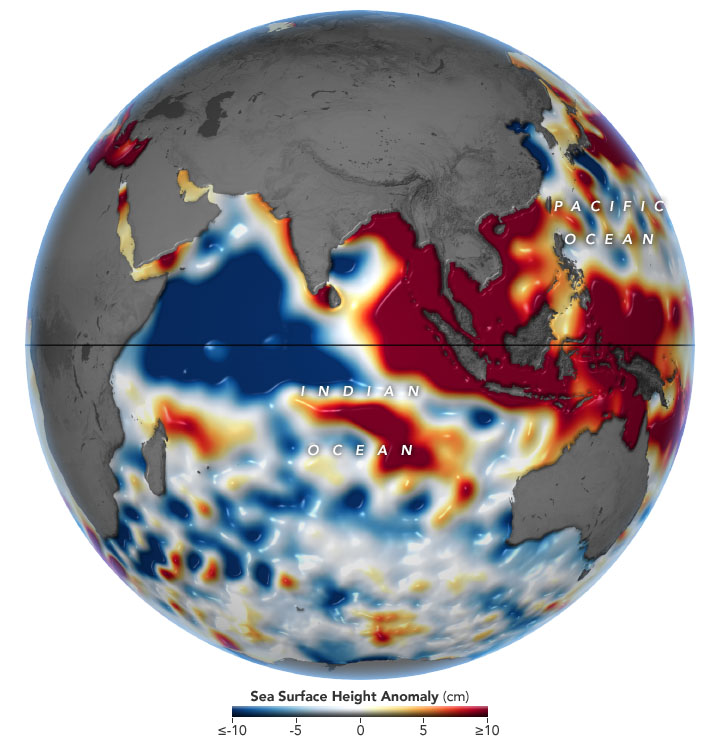

Scientists who study climate and weather teleconnections point to human-induced warming in the western Pacific and the ongoing La Niña as causes of the troubles in eastern Africa. The cooling of the eastern tropical Pacific and the warming of the western Pacific disrupts weather patterns all over the world. While rainfall increases substantially around Indonesia, the effect in eastern Africa is suppressed rainfall. With La Niña still dominating the conditions in the western Pacific—shown above in December 2021—and expected to persist through the first few months of 2022, food security researchers fear there may be another failed gu rainy season ahead.

In their report, FEWS NET analysts wrote: “A long sequence like this is very rare, with the last possibly being nearly 40 years ago during 1983-84. Since 1983, the population of Kenya, Ethiopia, and Somalia has tripled, dramatically increasing the number of people exposed to drought hazards.”

“Climate change, interacting with natural La Niña climate conditions, has increased the frequency of droughts in this region,” said Chris Funk, director of the Climate Hazards Center at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “But using the latest generation of climate models, we can now predict—and have predicted—many of the recent poor rainy seasons.”

“Satellites tell us that the 2021 October-December season was similar to the disastrous 2010 season, and our forecast models are suggesting a high chance of a March-May 2022 season similar to 2011,” he added. “A poor March-May 2022 season would result in an unprecedented sequence of four below-normal rainfall seasons, which would further exacerbate the current humanitarian challenges.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using data from the Climate Hazards Center, the Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS Net), and modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2021) processed by the European Space Agency courtesy of Josh Willis/NASA/JPL-Caltech. Story by Michael Carlowicz.