The transformative power of water, wind, and gravity is on full display in Iraq’s Ga’ara Depression. The rim of this large, oval-shaped basin near the Iraq-Syria border rises a few hundred meters along its southern and western edges.

Geologists call the rock at the bottom of the basin the Ga’ara Formation. It is made up of alternating layers of sandstone and soft claystone that formed roughly 300 million years ago, when the area was covered by a shallow sea. Later, types of carbonate rock (dolomite, limestone, and marl) were layered on top of the Ga’ara Formation, and the entire sequence of rock was gradually pushed up into a dome shape by tectonic forces.

The dome achieved its maximum height about 30 million years ago. Erosive forces have since chipped away at this layer-cake of rock. The combined effects of water, wind, and gravity wore through the thin carbonate layers at the top of the dome, and then hollowed out the oval-shaped depression from the soft, crumbly rock of the Ga’ara Formation, leaving behind a rim of tougher carbonates. These steep cliffs along the southern rim have played a key role in widening the basin over time. The regular stream of landslides and rockfalls that tumble down the cliffs have caused the southern rim to continue moving south over the years.

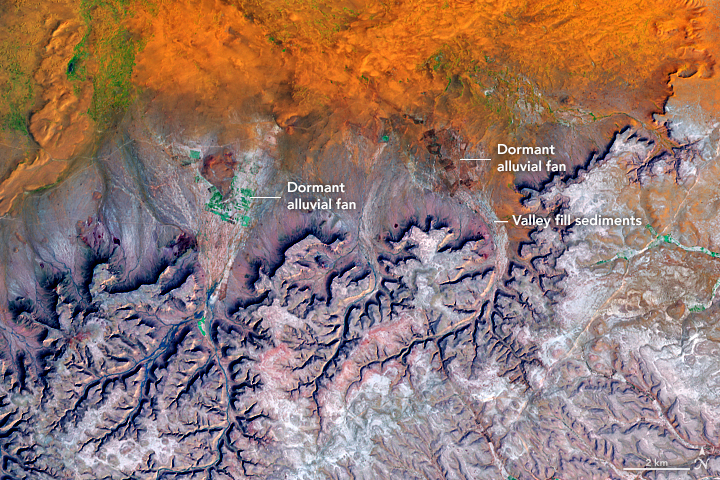

The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 acquired this image of the basin on August 27, 2017. It is derived from observations of shortwave infrared, near infrared, and green light (bands 7-5-3), a combination that makes it easier to distinguish different rock and soil types and to detect the presence of moisture.

While rain is infrequent here, it can fall in intense bursts during the short wet season. These sporadic deluges can transform dried-out channels (known locally as wadis) into roaring rivers that, over time, carve the sharp valleys in the limestone plateaus along the western and southern rim. When the rushing streams drain into the Ga’ara’s relatively flat interior, they spread out and become braided streams with multiple, interlacing channels that spread sediment over a wide area.

As the streams slow, their capacity to carry sediment diminishes, causing sandbars to accumulate along the channels. Over time, the channels migrate back and forth, creating fan-shaped deposits of sediment known as alluvial fans. Some of the fans, especially along the southern rim, are older and dormant; others, mainly along the western rim, are smaller and actively growing.

While geologists think rockslides and flowing water were especially influential in carving out this depression, wind played a key role as well. During drier periods, fine sand on the basin floor often gets lifted by wind storms and blown out of the basin in an easterly direction.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Adam Voiland.