Communities in the Great Lakes Basin have spent years battling invasions of carp and harmful algae. Now they have another formidable foe: a fast-growing reed that can take over wetlands. Phragmites australis is a hardy, aggressive species that can grow to 5 meters (17 feet) tall. In the process, the plant often pushes out native salt marsh vegetation.

Phragmites australis is considered an invasive species (non-native) in some regions. It grows in fresh and salt water—especially in recently disturbed wetlands—and it thrives in lakes and bays where there are high levels of fertilizer runoff from farms and suburban development. Once phragmites populates an area, it is difficult to eradicate because of its vast root systems and dense growth. Individual plants spread by dispersing seeds or by sending out shoots and roots (rhizomes and stolons) above and below ground.

These reeds grow fast, blocking access to the water by recreational users and animals. They are not appealing as food or shelter for most wildlife, with the exception of some birds that nest in tall grasses. After phragmites dies, the reeds can pile up and raise the floor of the marsh, preventing water from naturally flooding a marsh with critical nutrients and moisture. It also leaves behind stalks and leaves that dry out and become combustible matter that can feed wildfires.

Recently, wildlife managers gained a new tool to understand phragmites around the Great Lakes. Building upon research by the Michigan Tech Research Institute and the U.S. Geological Survey, researchers from the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative and NASA’s DEVELOP applied sciences program created a mapping tool to identify current and future areas at risk of phragmites invasions. The researchers examined satellite data and matched it with ground-based observations of the coastal landscape, such as the roughness of the terrain, the distance from agriculture or roads, and the coldest seasonal temperature. Each factor affects the likelihood of phragmites growth.

Researchers from the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative and NASA’s DEVELOP applied sciences program built upon research by the Michigan Tech Research Institute and the U.S. Geological Survey to create a mapping tool to identify current and future areas at risk of phragmites invasions. The researchers examined satellite data and matched it with ground-based observations of the coastal landscape, such as the roughness of the terrain, the distance from agriculture or roads, and the coldest seasonal temperature. Each factor affects the likelihood of phragmites growth.

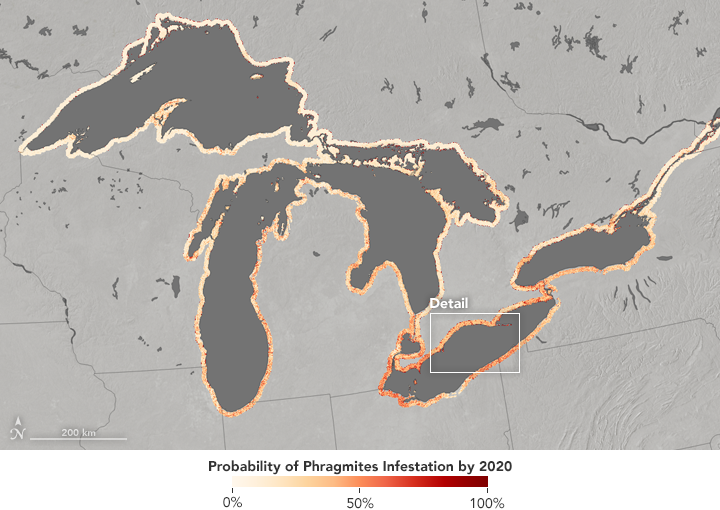

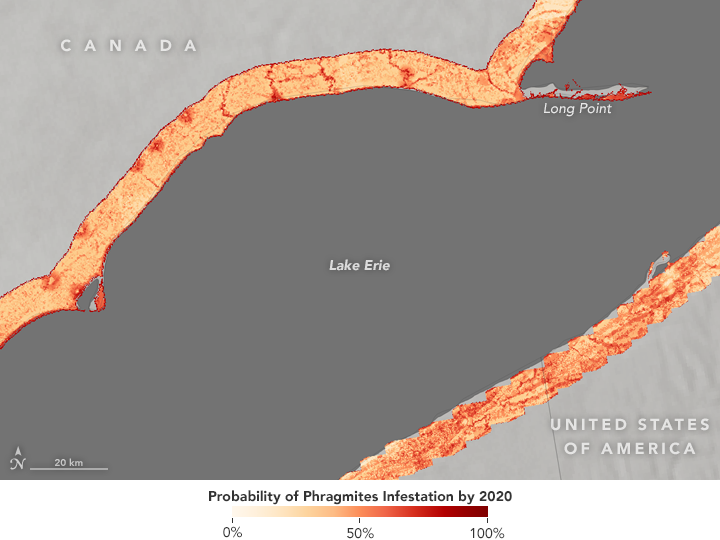

The maps on this page are derived from the team’s model of conditions in 10-kilometer-wide swaths along the lake shores. They show areas most likely to be invaded by phragmites by the year 2020. Areas with the highest probability of invasion appear in dark red, while lower risk appears in light orange to white. The close-up shows the northern coast of Lake Erie, including the Long Point Peninsula.

The key to stemming the tide of phragmites invasions is knowing where the plants are most likely to grow. As indicated by the maps, the reeds often show up where streams and rivers flow into the lake. Using such maps, watershed managers can decide on a course of action, which often means burning the phragmites or spraying them with herbicides.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Jesse Allen, based on data from Mike Ruiz and Sean McCartney, NASA DEVELOP. Photograph courtesy of Greg Norwood, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Story by Pola Lem.