In 2014, an established crack began spreading rapidly through the Larsen C Ice Shelf—a huge slab of floating ice along the Antarctic Peninsula. By April 2017, only 16 kilometers (10 miles) of ice separated the tip of that crack from the open sea.

Predicting when the cracking shelf will set loose an iceberg is a challenge because ice fracturing depends on several factors, some of which are poorly understood. The iceberg, which is likely to be the size of Rhode Island, could break off any time from days to years from now, according to scientists from Project MIDAS, a United Kingdom-based group that is monitoring the event.

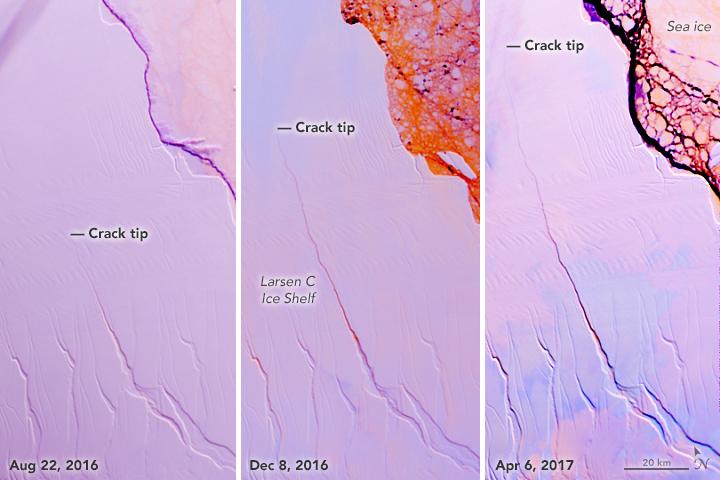

The Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR) instrument aboard NASA’s Terra satellite captured images of Larsen C on August 22, 2016, when the rift was 130 kilometers long; on December 8, 2016, when the rift stretched 145 kilometers; and on April 6, 2017, when it was 180 kilometers. The false-color composites were created with images from MISR’s backward-, vertical-, and forward-pointing cameras. By combining the different angles in one image, it is possible to discern the "texture" of the surface. Rougher ice and water surfaces appear orange; areas with smooth ice appear blue.

The ice shelf is generally smoother than the sea ice, with the exception of the crack—an indication that it is actively growing. In August, the sea ice formed a smooth, continuous surface due to cold, winter weather. MISR detected rougher (more orange) surfaces in the sea in December 2016 because warm summer weather had melted the sea ice to a point where many small pieces of ice were floating on the surface. In April, the sea ice was partially broken up.

While a large iceberg breaking from an ice shelf like Larsen C is a routine process that does not increase sea level, this rift is being closely watched because it could be an early step in the complete disintegration of the ice shelf. Ice shelves help hold adjacent land-based glaciers in place, and it is the loss of this land-based ice that increases sea level.

However, even a complete loss of Larsen C and all of its tributary glaciers would only have a minor effect. The ice shelf holds back the equivalent of one centimeter of global sea level rise, according to Helen Fricker, a member of NASA’s sea level change science team.

Still, the crack in Larsen C could be a bellwether for ice shelves elsewhere in Antarctica. “What we are seeing on Larsen C has implications for the big ice shelves farther south that hold considerable (sea level) potential,” said Eric Rignot, another member of the sea level change team. “The loss of these larger ice shelves and the resulting acceleration of glacial calving could amount to meters of sea level rise in the decades and centuries to come.”

Read more about Larsen C and sea level from NASA’s sea level change portal.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Jesse Allen, using data provided by the NASA/GSFC/JPL, MISR Team. Story by Adam Voiland, based on information from Pat Brennan (NASA JPL), Abigail Nastan (NASA JPL), and Adrian Luckman (Swansea University).