This week marks the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service. We are celebrating this milestone with a gallery of images that you can see here.

On most summer days, a trip to North Carolina’s Outer Banks means a peaceful day at the beach soaking up the sun and playing in the waves. But there is evidence all around that this beach is not always so serene. The very existence of these barrier islands is due to the power of wind and water.

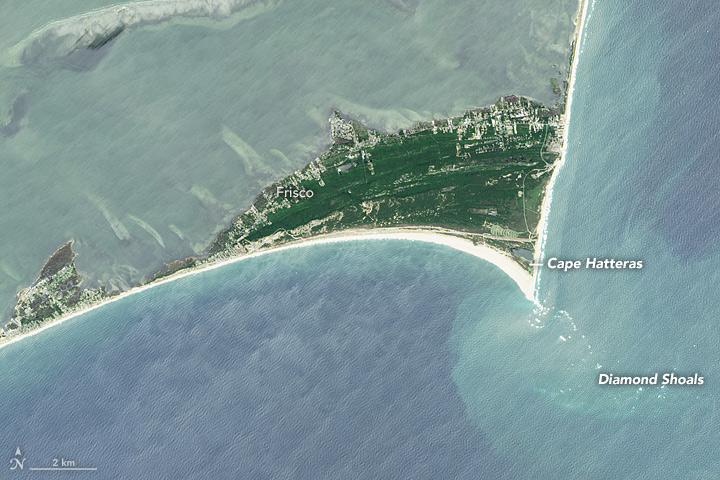

The images above show a segment of the barrier islands in the vicinity of Cape Hatteras National Seashore. The park’s origins date back to the 1930s, when Congress authorized the creation of this first “national seashore park” in the United States. It wasn’t until 1953 that the National Park Service acquired enough land to establish the park, and another five years before facilities were in place and the park could formally open.

These islands have been in flux long before the park was established, and they continue to change today. These images show a moment in time on June 7, 2015, captured with the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on the Landsat 8 satellite. Various stages of island evolution—from build-up to erosion—are all visible along the island chain.

Stanley Riggs, a scientist who in the mid 1960s developed the coastal and marine science program at East Carolina University, pointed out some notable features. Skinny parts of the island chain, which appear mostly white without any green vegetation, are “simple” barrier islands. These areas are generally eroding and thinning. The shoreline continues to recede and weak spots form, at which point water from the Atlantic Ocean can break through and form an inlet.

“If you can’t see green vegetation,” Riggs said, “that means the area is ready to break in the next storm to form an inlet.”

The year that these images were acquired was a relatively quiet one for storms. In other years, however, hurricanes and nor’easters have opened multiple inlets in a single season. Within a year or two after an inlet opens up, a flood tide delta typically forms behind it and continues the natural cycle of island rebuilding. That cycle is influenced, however, by the human development and maintenance of structures such as highway 12—the road that runs like a spine down the length of North Carolina’s barrier islands.

In contrast, the green vegetated areas along the islands are usually wider and older “complex” barrier islands. The second image shows a detailed view of one such area at Cape Hatteras. In this view, you can see parallel east-west ridges that have built up over time behind the tip of the cape. The relative height of the dunes and distance from the ocean have allowed forests to grow. These are also the more protected and therefore urbanized parts of the island chain.

Still, the wind and waves take a toll, eroding the east-facing shoreline of the cape and moving sand southward to Diamond Shoals. This huge pile of sand just below the ocean surface extends for about 10 miles (16 kilometers)—and that’s small compared to the shoals extending out from other capes in North Carolina, which Riggs calls the “graveyards of the Atlantic” for the hazard they have long posed to ships.

Areas west of the islands do not escape the forces of nature. Parts of the mainland submerged by rising sea levels have transitioned to sandy shoals, which appear as various shades of white on the west side of Pamlico Sound. These sandy areas have a depth of 10 feet (3 meters) or less. The center of Pamlico Sound is darker and deeper, about 20 feet (6 meters). Then, toward the eastern side of the sound the water becomes shallow again as you approach the barrier islands, an area known as Hatteras Flats.

Storms have even built a mini barrier island on Hatteras Flats—miles out in the sound, but walkable from almost anywhere on the main barrier islands. The flats support rich grass beds, marshes, and nutrient beds that feed the mid-Atlantic fisheries. The park area as a whole is “an incredible habitat for wildlife,” Riggs said. Birds overwinter on the islands, and sea turtles nest on its beaches.

The islands in their natural state are resilient. But storms and coastal change can be hard on infrastructure and the roads that visitors use to access the park.

“A little rise in sea level and next series of storms could do a number on that highway out there,” Riggs said. “There will always be a national seashore—you just might have to get there by boat.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Caption by Kathryn Hansen.