The Floating Forest concept is all about getting more eyeballs on Landsat imagery. Citizen scientists—recruited via the Internet—are instructed in how to hunt for giant kelp in satellite imagery. They are then given Landsat images and asked to outline any giant kelp patches that they find. Their findings are crosschecked with those from other citizen scientists and then passed to the science team for verification. The size and location of these forests are catalogued and used to study global kelp trends.

In addition to examining the California coast, which Byrnes and Cavanaugh know well, the Floating Forests project has also focused on the waters around Tasmania. Tom Bell and collaborators in Australia and New Zealand have noticed dramatic declines in giant kelp forests there over the past few decades. The decline has been so rapid and extensive that giant kelp are only found now in isolated patches.

Off the east coast of Tasmania, 95 percent of the kelp has disappeared since the 1940s. False-color Landsat images from September 1999 (top) and September 2014 (bottom) provide evidence of recent kelp forest disturbance. (NASA Earth Observatory image by Mike Taylor, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey)

Off Tasmania’s east coast, 95 percent of the kelp has disappeared since the 1940s. The loss has been so stark that the Australian government listed Tasmania’s giant kelp forests as an “endangered ecological community“— the first time the country has given protection to an entire ecological community. The loss is so stunning because this was a place where kelp forests were once so dense that they merited mention on nautical charts.

Cool, subarctic waters once bathed Tasmania’s east coast, but warmer waters (as much as 2.5ºC (4.3ºF) warmer) have brought many invasive species that feast on giant kelp. Compounding the matter, the overfishing of rock lobsters has removed a key predator of the long-spined sea urchins (which eat kelp). The ecosystem’s new protected status could help curb overfishing and restore the lobsters, which would help diminish the threat from sea urchins.

This U.S. Hydrographic Service chart from 1925 shows Prosser Bay, Tasmania, and the distribution of giant kelp. (Source: Edyvane at al, 2003)

Using Landsat to monitor the kelp forests and establish trends may shed more light on what is happening off of Tasmania. “We believe the data from Floating Forests will allow us to better understand the causes of these declines,” said Cavanaugh.

As of November 2014, more than 2,700 citizen scientists had joined Byrnes and Cavanaugh to look for kelp in 260,000 Landsat images. All combined, the citizen scientists have now made more than one million kelp classifications. The response has exceeded expectations, and the project has been expanded faster than originally planned.

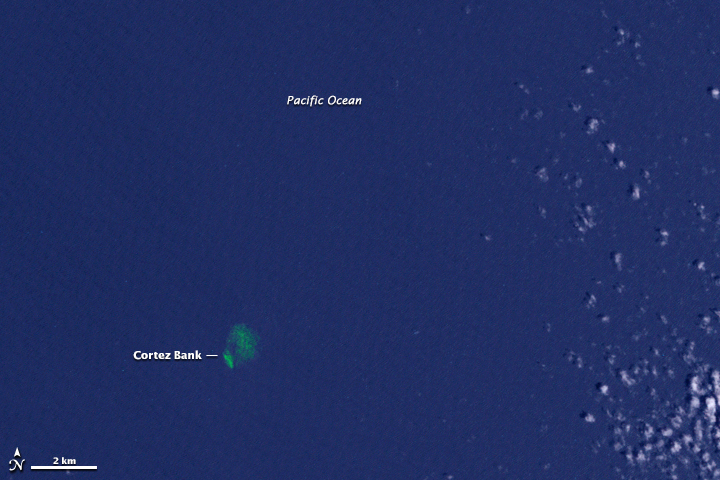

Already a discovery has been made. A citizen scientist found a large patch of giant kelp on the Cortez Bank, an underwater seamount about 160 kilometers (100 miles) off the coast of San Diego. While giant kelp on this submerged island—which comes within feet of the surface at some points—had been documented by divers and fishermen in the past, the full extent of the kelp beds was unknown.

A citizen scientist found satellite evidence of an outlying kelp forest that was previously known only to divers and local fishermen. (NASA Earth Observatory image by Mike Taylor, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey)

“The first few months of Floating Forests have been a huge success, and we are hopeful that we will soon be able to expand the project to other regions,” Cavanaugh said. “Our ultimate goal is to cover all the coastlines of the world that support giant kelp forests.”

To learn how to participate in the Floating Forests project, visit their web page.