When the oil refinery in San Nicolas, Aruba, shut its doors in 2009, a silent change took place. Above the azure seas and chimney stacks, the air began to clear as sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions plummeted.

Invisible to the human eye, SO2 can disrupt human breathing and harm the environment when it combines with water vapor to make acid rain. It tends to concentrate in the air above power plants, volcanoes, and oil and gas infrastructure, such as the refinery in Aruba. Using data collected by the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) on the Aura satellite, the researchers mapped the noxious gas as observed over a decade.

“Previous papers focused on particular regions; this is the first real global view,” said Nickolay Krotkov of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, an author of the study published in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. The data gives a mixed outlook across the planet, with emissions rising in some places (India) and falling in others (China and the United States).

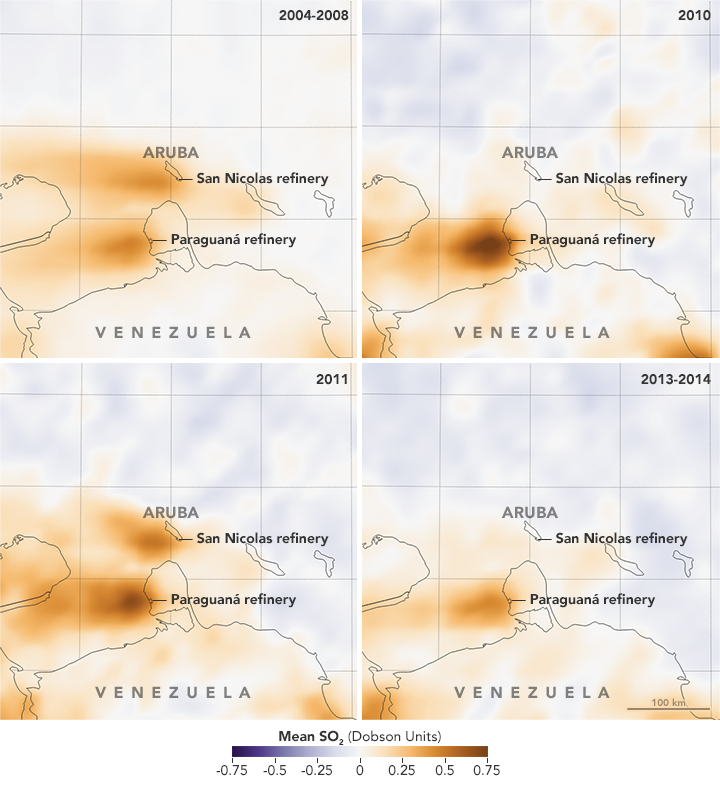

As a regional example of the changes, the researchers examined the fluctuations in SO2 levels around Aruba. The prevailing winds, or trade winds, naturally blow air to the west of the refineries. Light purple patches over the ocean indicate areas where SO2 has decreased over time.

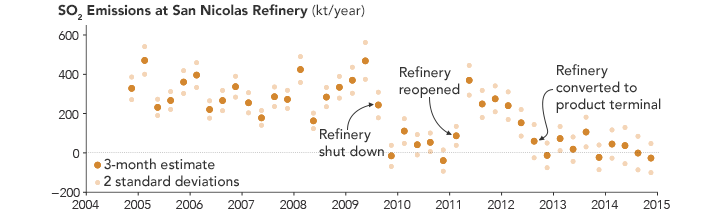

After the San Nicolas refinery halted operations in late 2009, its SO2 output dropped. But by mid-2011, the refinery was reopened and SO2 emissions were back to their previous levels of roughly 350 kilotons per year. When low oil prices caused the refinery to cut back production, emissions follow a downward curve until mid-2013, when the San Nicolas plant was converted to a product terminal. The graph below plots its emissions over the years.

The same downturns in the global oil market that have put the fate of the San Nicolas operation in limbo have also affected the nearby Paraguaná Refinery Complex, which is the largest of its kind in Latin America. The 2010 and 2011 images show dark spots in the Gulf of Venezuela—likely, emissions from Paraguaná.

As for San Nicolas, emissions are expected to rise again in the coming years. Venezuelan-owned Citgo Petroleum Corporation signed a 15-year lease on the refinery in late 2016 and plans to reopen the site by 2018.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using emissions data courtesy of Fioletov, Vitali E., et al. (2017). Caption by Pola Lem.