It all began with a single, pregnant mite. Within a few years, thousands of acres of bright green forests would yellow and wither.

From its home in the Eastern Hemisphere, the mite crossed the Atlantic Ocean by ship or winds and made landfall in Martinique. The journey likely occurred sometime in 2003. Within a few years, that mite and its offspring reproduced to create a tiny, gnawing army that felled trees on multiple Caribbean islands. By 2006, the ravenous mites had reached Puerto Rico, where they chewed through coconut palms, bananas, and plantains along the coast. DNA tests show that all of those insects can trace their lineage back to that one mite.

It’s not a myth or a horror story. It’s a series of events and circumstances that prompted research by a group of NASA-funded researchers.

“We were trying to determine what a palm mite infestation looks like from space, and we didn’t have any previous data,“ said Sara Lubkin, the project lead and a professor at the University of Mary Washington. Working together with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the University of Puerto Rico, Lubkin and her team tracked the mite’s spread across Puerto Rico by mapping changes to vegetation (such as yellowing) and differences in canopy structure. By counting the number of pixels of affected palms, the researchers were able to get a sense of the scale of the problem in Puerto Rico. The work was funded through NASA’s DEVELOP program, which “addresses environmental and public policy issues” using Earth observations.

“There are a bunch of tiny areas of palms in Puerto Rico that are just 100 meters wide,” said Julia Marrs, a doctoral student at Boston University and researcher on the DEVELOP team. Because the palms fringe the coast in such thin stands, mapping the spread of the mites with satellite imagery designed for wider views presented a challenge. The researchers combined imagery from several instruments, including the Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) on Landsat 7, the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8, the Hyperion multispectral imager on Earth Observing-1 (EO-1), and aerial photography.

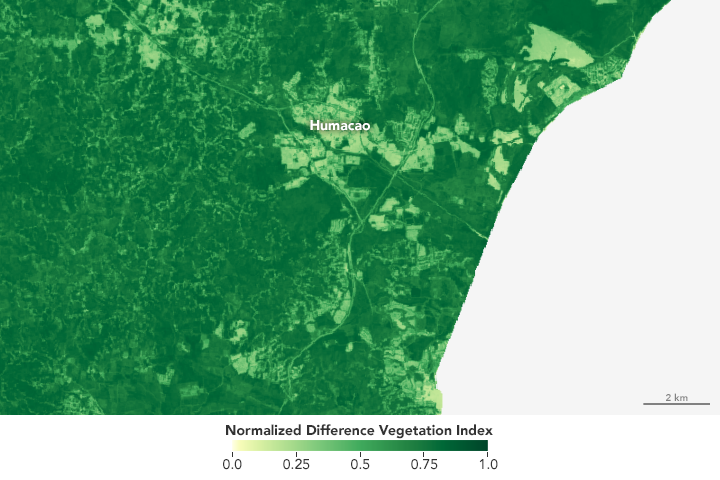

Researchers used the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and other indices to map healthy, vegetated areas. Areas with extensive human settlements or with less vegetation appear yellower on the index. Indices like NDVI also detect unhealthy vegetation. By combining spectroscopy with ground observations from the University of Puerto Rico, researchers were able to pinpoint affected palm stands.

The team found a way to see from space the results of a process that is typically viewed under a microscope. Roughly the size of a pinprick and barely visible to the naked eye, the adult female mite measures 245 microns (0.01 inches) long, slightly larger than the male. When mites feed, they crawl to the underside of a leaf. Then they extend whip-like appendages called chelicerae to puncture the plant tissue and remove the cell contents, sucking them out like jello out of a cup.

Palm mites are responsible for millions of dollars of agricultural damage around the Caribbean, potentially reducing coconut harvests by half in the Caribbean Basin. The mites are highly adaptable, which is part of what makes them so destructive. Efforts to map their spread can help mitigate current mite infestations and monitor and prevent future outbreaks.

In the future, Lubkin hopes to apply this approach to countries with larger palm plantations, like Brazil and Costa Rica. “The real test is to apply this to a larger area,” she said.

NASA Earth Observatory map by Joshua Stevens, using NDVI data courtesy of Sara Lubkin/Unversity of Mary Washington. Caption by Pola Lem.