Though photographers, seismologists, and automated webcams have been documenting the eruption near Iceland’s Bardarbunga volcano from the ground, satellite imagery has been scarce because of persistent cloud cover and a relatively small number of spacecraft that collect images at high latitudes. But in the past few days, NASA satellites have finally been able to observe the event from orbit.

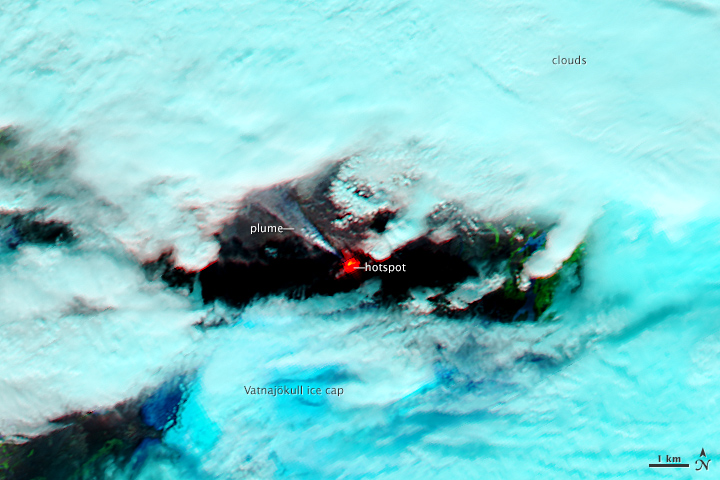

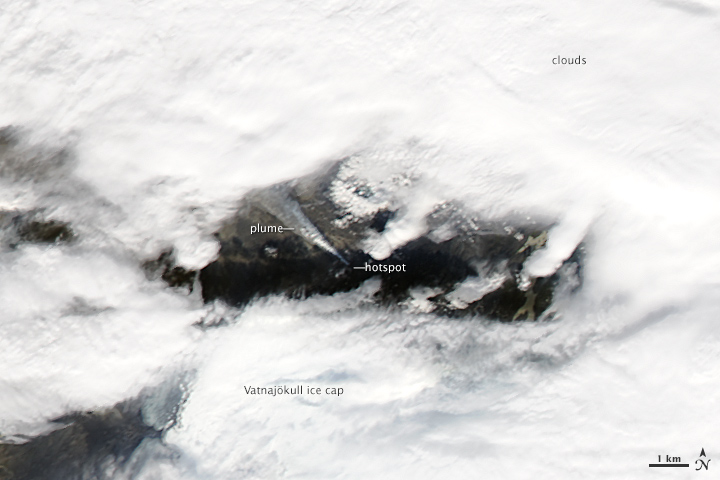

At 12:45 p.m. Universal Time on August 31, 2014, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite acquired these views of the eruption (above). The top, false-color image uses a combination of infrared and visible light (MODIS bands 7-2-1) to highlight the heat signatures of the erupting lava and to distinguish glacial ice from clouds. In the lower, natural-color image, the lava appears black.

Overnight on September 1, the Advanced Land Imager (ALI) on NASA’s Earth Observing-1 (EO-1) satellite captured the first high-resolution view of the scene. The image below is a composite of a natural-color observation from August 27 overlaid with an infrared (IR) night view from September 1. The night view combines shortwave IR, near IR, and red wavelengths (bands 9-7-5) to tease out the hottest areas within the vent and lava field. The image shows at least a 1-kilometer fissure and lava flowing in channels. The front of the flow has been moving mostly to the northeast in recent days. (Download the large images to see the day and night views separately.)

Swarms of earthquakes began near the volcano on August 16, and tremors have persisted in the weeks since (as many as 500 per day). To date, the Bardarbunga eruption has produced lava flows and fountains—some reaching 200 meters, or 650 feet—but no large ash plumes. As of September 3, the Icelandic Met Office reported that the new lava field spanned an area of 7.2 square kilometers (2.8 square miles), slightly larger than Gibraltar.

Scientists are watching closely to see how molten rock at and below the surface will interact with glacial ice, surface melt, and groundwater; their concern is for flooding on or near the Holuhraun lava field, or for steam explosions as water is superheated by the magma. Icelandic researchers also have surmised from GPS measurements of the deforming land surface that more magma is entering the dyke than is erupting on the surface.

NASA imagse by Jeff Schmaltz, LANCE/EOSDIS Rapid Response and Jesse Allen, using EO-1 ALI data provided courtesy of the NASA EO-1 team. Caption by Mike Carlowicz, with image interpretation from Ashley Davies, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.