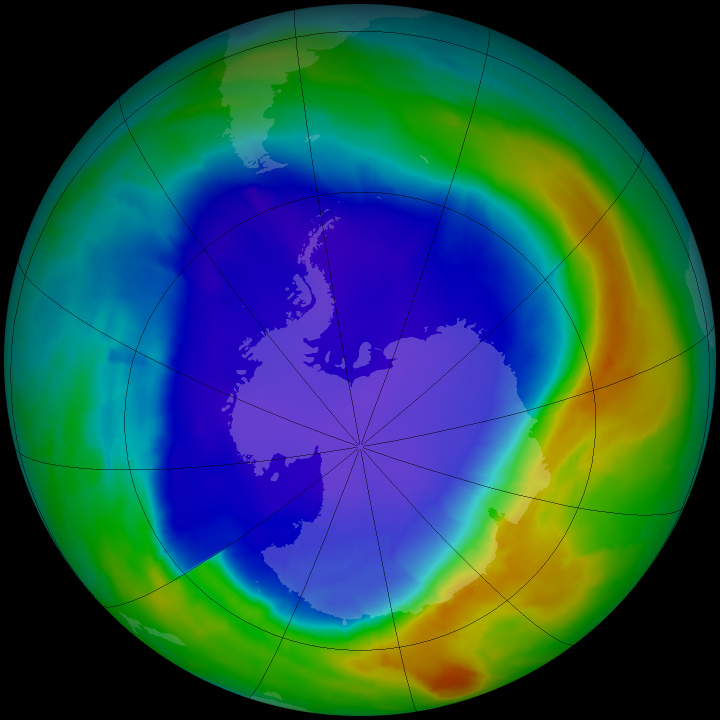

The ozone hole over Antarctica was slightly smaller in 2013 than the average for recent decades, according to data from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) on NASA’s Aura satellite and the Ozone Monitoring and Profiler Suite (OMPS) on the NASA-NOAA Suomi NPP satellite. The average size of the hole in September–October 2013 was 21.0 million square kilometers (8.1 million square miles). The average size since the mid 1990s is 22.5 million square kilometers (8.7 million square miles).

The single-day maximum area reached 24.0 million square kilometers (9.3 million square miles) on September 16—an area about the size of North America. The largest single-day ozone hole ever recorded by satellite was 29.9 million square kilometers (11.5 million square miles) on September 9, 2000.

The image above shows ozone concentrations over the South Pole on September 16, 2013, as measured by OMI. The animation below shows the evolution of the ozone hole, including a plot of the area and concentrations, from July 1 to October 15, 2013. To see ozone holes since 1979, visit World of Change: Antarctic Ozone Hole.

The ozone hole is a seasonal phenomenon that starts during the Antarctic spring (August and September) as the sun begins rising after winter darkness. Pole-circling winds keep cold air trapped above the continent, and sunlight catalyzes reactions between ice clouds and chlorine compounds that begin eating away at natural ozone in the stratosphere. In most years, the conditions for ozone depletion ease by early December, when the seasonal hole closes.

“There was a lot of Antarctic ozone depletion in 2013, but because of above average temperatures in the Antarctic lower stratosphere, the hole was a bit below average compared to ozone holes observed since 1990," said Paul Newman, an atmospheric scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

The size of the hole in any particular year is not enough information for scientists to determine whether the atmospheric conditions that cause the ozone hole have permanently improved. Levels of most ozone-depleting chemicals in the atmosphere have gradually declined as the result of the Montreal Protocol, an international treaty to phase out production of ozone-depleting chemicals. In the decades since the treaty, the hole has stabilized, with some meteorologically driven variations from year to year.

Science teams from NASA, NOAA, and the World Meteorological Organization have been monitoring the ozone layer on the ground and with a variety of instruments on satellites and balloons since the 1970s. Long-term ozone-monitoring instruments have included the Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer, the second generation Solar Backscatter Ultraviolet Instrument, the Stratospheric Aerosol and Gas Experiment series of instruments, and the Microwave Limb Sounder.

NASA animation by Robert Simmon, using imagery from Ozone Hole Watch. Caption by Mike Carlowicz.