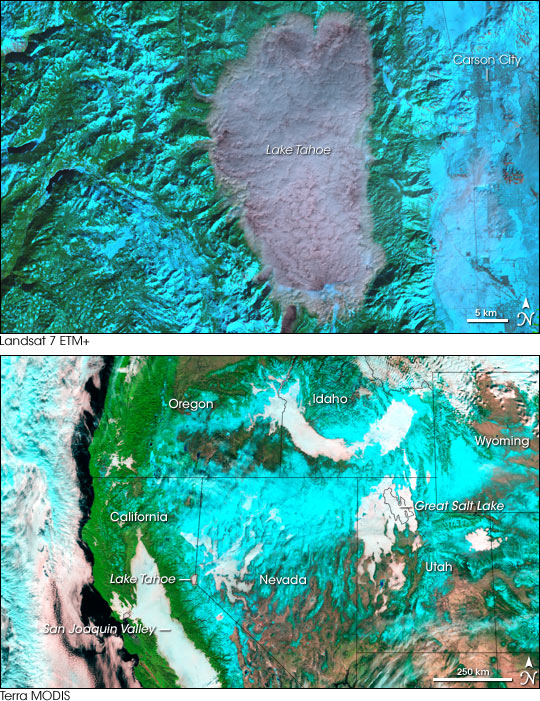

Smooth white fog fills the crevices of the western landscape like spilled milk puddling on an uneven platter. Up close, the low-lying cloud has a consistency that is closer to oatmeal, with ripples and clots through which the black surface of Lake Tahoe can be glimpsed. This valley fog, seen by both the Landsat 7 ETM+ (top) and Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) (bottom) sensors, lingers most over water: the smiling arch of the Snake River in Idaho, the Great Salt Lake in Utah, and the San Joaquin River in California, but it also traces out the contours of mountain valleys across the western United States.

Valley fog forms on clear winter days when heavy cold air settles into the mountain valleys while warmer air moves over the surrounding mountains. Fog forms when the frigid ground cools the air immediately above it. The cooling air thickens into fog as water condenses. Air farther from the Earth’s surface is warmed by the sun, trapping the layer of cold air beneath it. The condition is called a temperature inversion, and it can last several days in the mountains of the Intermountain West during the winter.

Seen from an airplane, valley fog would give this winter landscape a flat appearance, with the whitened valleys blending into the snow-capped mountain tops. These false color images create the opposite effect, with the fog defining low elevations. While the images do not have identical color combinations, both were made using infrared light, so that the snow is bright blue while the fog is white. Exposed vegetation is green, and bare earth is a pink-tinted tan. In the MODIS image, clouds over the Pacific Ocean are blue and white.

NASA images created by Jesse Allen, Earth Observatory, using data provided courtesy of the Landsat Project Science Office and the Goddard Earth Sciences DAAC.