Record snowfall in recent years has not been enough to offset long-term drying conditions and increasing groundwater demands in the U.S. Southwest, according to a new analysis of NASA satellite data.

Declining water levels in the Great Salt Lake and Lake Mead have been testaments to a megadrought afflicting western North America since 2000. But surface water only accounts for a fraction of the Great Basin watershed, which covers most of Nevada and large portions of California, Utah, and Oregon. Far more of the region’s water is underground. That has historically made it difficult to track the impact of droughts on the overall water content of the Great Basin.

A new look at 20 years of data from the GRACE (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment) and GRACE-FO satellites shows that the decline in groundwater in the Great Basin far exceeds stark surface water losses. Over about the past two decades, the underground water supply in the basin has fallen by 16.5 cubic miles (68.7 cubic kilometers). That’s roughly two-thirds as much water as the entire state of California uses in a year and about six times the total volume of water that was left in Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir, at the end of 2023.

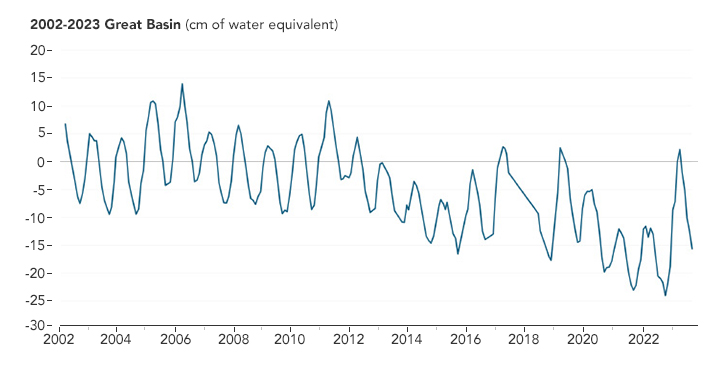

The map above shows changes in stored water between April 2002 and September 2023. Notice that some of the largest rates of loss (red) occurred across parts of Southern California, which has been severely affected by water declines in the Great Basin region. Data for this map and the chart below were derived from the joint German DLR-NASA GRACE missions. GRACE-based maps of fluctuating water levels have improved recently as researchers have learned to parse more and finer details from the dataset.

The satellite-derived data show a seasonal rise in water each spring due to melting snow from higher elevations, visible as the bumps in the chart above. But University of Maryland Earth scientist Dorothy Hall said occasional snowy winters are unlikely to stop the dramatic water level decline that’s been underway in the U.S. Southwest. This decline is apparent in the chart’s overall downward trend, especially after 2012. The finding came about as Hall and colleagues studied the contribution of annual snowmelt to Great Basin water levels.

“In years like the 2022–23 winter, I expected that the record amount of snowfall would really help to replenish the groundwater supply,” Hall said. “But overall, the decline continued.” The research was published in March 2024 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

“A major reason for the decline is the upstream water diversion for agriculture and households,” Hall said. Populations in the states that rely on Great Basin water supplies have grown by 6–18 percent since 2010, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. “As the population increases, so does water use.”

Runoff, increased evaporation, and the water needs of plants suffering from hot, dry conditions in the region are amplifying the problem. “With the ongoing threat of drought,” Hall said, “farmers downstream often can’t get enough water.”

According to the new findings, Hall said, “The ultimate solution will have to include wiser water management.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Wanmei Liang, using data from Hall, Dorothy, et al. (2024). Text by James R. Riordon/NASA’s Earth Science News Team, adapted from a story first published on June 17, 2024.