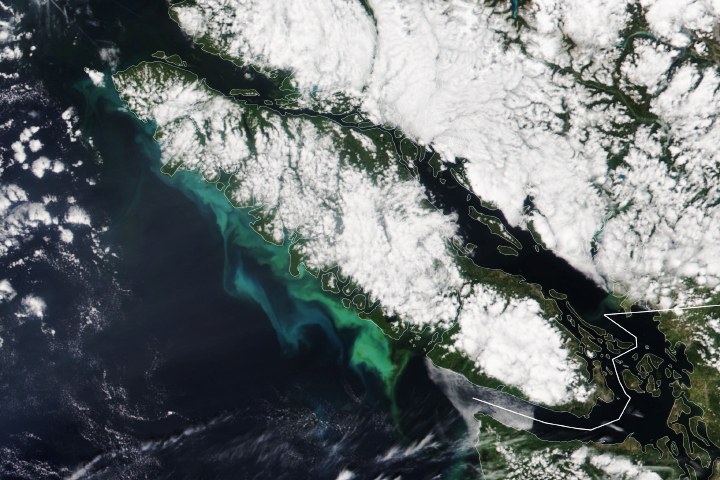

Bursts of phytoplankton are appearing in oceans, seas, gulfs, canals—and increasingly in lakes.

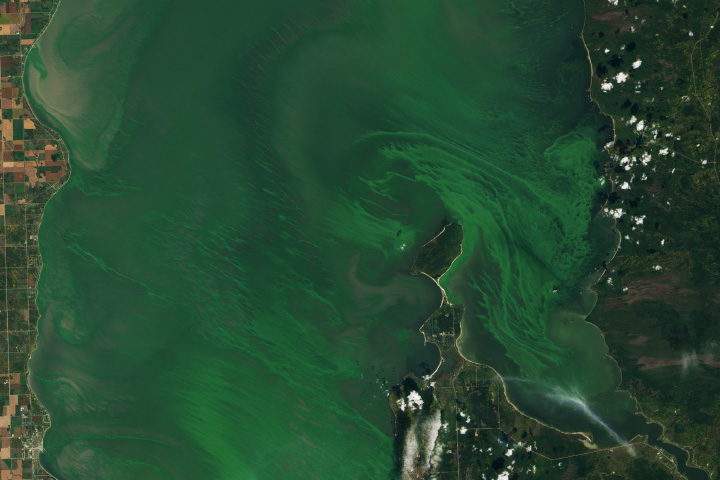

The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on the Landsat 8 satellite captured this image of an algal bloom on Lake Villarrica in Chile on May 2, 2023. Ground-based observations and analysis of additional satellite images suggest that cyanobacteria make up the light blue-green swirls in the natural-color image.

Lake Villarrica, which sits downslope of the volcano of the same name, attracts visitors with its scenic beaches and recreational opportunities. The lake is flanked by small cities and resort areas on its southern shore, with agricultural areas further afield. Runoff from development and agriculture carries nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorous into the lake. When populations of microscopic cyanobacteria spike in response, the blooms often show up in satellite images.

“Blooms in freshwater lakes are occurring more and more frequently,” said Lien Rodríguez-López, an environmental science researcher at San Sebastián University who studies Chilean lakes using remote sensing. A combination of warming surface waters and nutrient-laden runoff is likely behind the more-regular blooms.

In a recent study using Landsat imagery, Rodríguez-López estimated the amount of chlorophyll-a, an indicator of algal blooms, on Lake Villarrica from 2014 to 2021. She found that despite the lake’s overall good water quality, chlorophyll-a values spiked close to shore and near the cities of Villarrica and Pucón. She concluded that the most significant source of nutrients for these blooms came from urban pollution, though agriculture may also have played a role. In fact, the pollution is significant enough that the lake is transitioning from an oligotrophic state, with low nutrient levels and high clarity, to a mesotrophic one, with intermediate nutrient and biological-productivity levels, she added.

Additionally, warmer water provides a more hospitable environment for the algae. Like many bodies of water around the world, Lake Villarrica has been warming along with the climate. In another study, Rodríguez-López used Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) thermal bands to analyze the surface temperature of Chilean mountain lakes from 2000 to 2016. She reported statistically significant warming trends in 12 of the 14 lakes studied, including Villarrica. The trend, she wrote, is “consistent with site observations and an increased frequency of potentially toxic cyanobacterial blooms in Villarrica Lake.”

With the help of monitoring efforts by the community group Vigilantes del Lago, blooms have been documented in the lake nearly every summer (January or February) since 2008. Occasionally, they occur in autumn (April or May), like this most recent event. The most common cyanobacteria comprising these blooms are in the genus Dolichospermum, which can be toxic.

The frequency of potentially hazardous blooms has become cause for concern in local communities. Robust citizen science efforts have coalesced to monitor and protect these changing Chilean lakes, and remote sensing may offer an efficient way to complement labor-intensive ground-based work. According to Rodríguez-López, satellite imagery may even be used to create an early warning system to notify the public of algal blooms and develop policies aimed at preventing them.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Wanmei Liang, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Lindsey Doermann.

Image of the Day Water Water Color

Toxic blooms are becoming more frequent in Chile’s Lake Villarrica.

Image of the Day for May 22, 2023

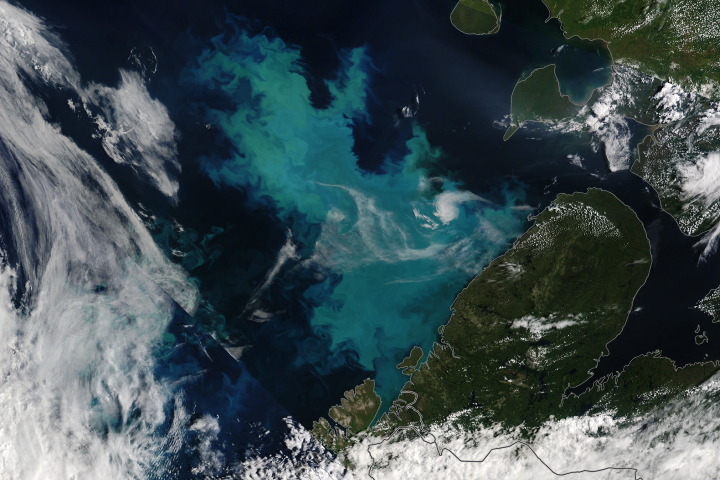

Floating, plant-like organisms reproduce abundantly when there are sufficient nutrients, sunlight, and water conditions. Extreme blooms of certain species can become harmful to marine animals and humans.