On September 28–29, 2022, Hurricane Ian roared across Florida as one of the most potent storms ever to make landfall in the state. The category-4 hurricane brought sustained winds of 150 miles (240 kilometers) per hour and several feet of storm surge to the southwestern coast of Florida, before dropping more than a foot of rain in wide swaths across the state.

In the hours after the storm passed, millions of residential and business customers lost electric power and light. The Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the NOAA–NASA Suomi NPP satellite captured views of some of those losses as they appeared on September 30, 2022.

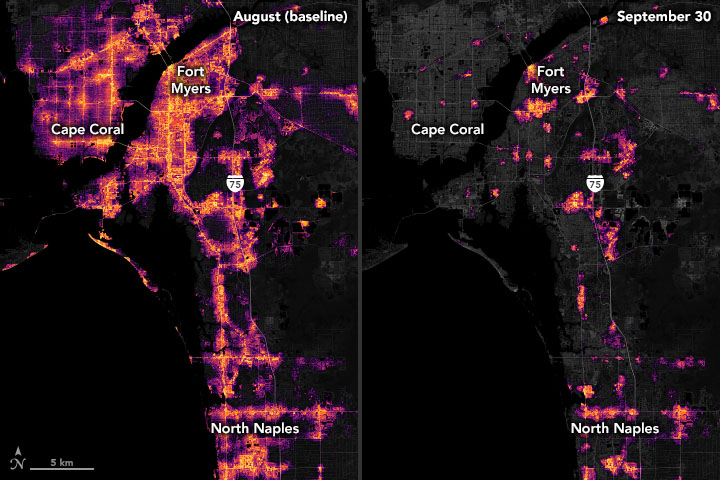

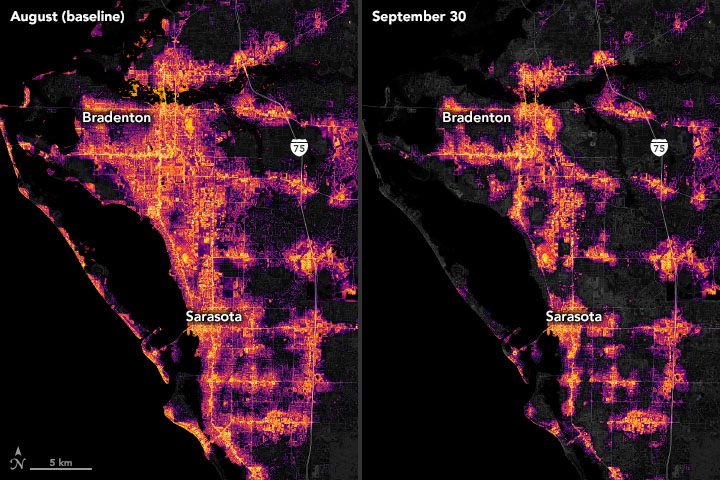

The images above and below focus on the metropolitan areas of Fort Myers and Bradenton/Sarasota, which were among the worst-hit communities. VIIRS has a low-light sensor—the day-night band—that measures nighttime light emissions and reflections. Scientists with the Black Marble Project at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Science Systems and Applications, Inc. (SSAI), and the University of Maryland, College Park (UMD) processed VIIRS data to show lights before and after Ian passed through the cities. Data from September 30 were compared to a pre-storm composite (August) and overlaid on landcover data collected by Landsat 8 and 9.

“As disasters often affect an entire region, the ability to capture widespread outages in a distributed energy system is extremely useful for damage assessment,” said Ranjay Shrestha, an SSAI scientist with the Black Marble group. “Combining socioeconomic and population data with nighttime light-derived metrics further helps us understand the interaction between power restoration rates and vulnerable populations.”

According to unofficial estimates, roughly 580,000 of Florida’s 11 million business and residential customers remained without power on the afternoon of October 3, down from roughly 2.7 million on September 29. Outages were concentrated around Lee, Charlotte, and Sarasota counties in the southwestern part of the state. Thousands of utilities workers from 34 states traveled to Florida to help restore power lines and other equipment.

The VIIRS day/night band makes it possible to distinguish the intensity of lights and to observe how they change. Nighttime imagery is sometimes used by relief agencies to identify areas that are most in need of aid and support. “Our team has been developing standardized approaches for power outage and recovery assessment that aim to assist local communities in improving resilience against the impacts of climate change and extreme weather events,” said Zhuosen Wang, a University of Maryland scientist and Black Marble product principal investigator.

Precision is critical for studies with night lights. Raw, unprocessed images can be misleading because moonlight, clouds, pollution, seasonal vegetation—even the position of the satellite—can change how light is reflected and can distort observations. The processing by the Black Marble team accounts for such changes and filters out stray light from sources that are not electric lights.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Black Marble data courtesy of Ranjay Shrestha/NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey, and data from OpenStreetMap. Story by Michael Carlowicz.