Among surfers, the term “heavy” can refer to any wave that is particularly dangerous. That includes waves that are literally heavy, heaving a crushing amount of water toward the shore and onto unlucky surfers. The waves off the coast of Teahupo’o in southern Tahiti have been called the heaviest in the world.

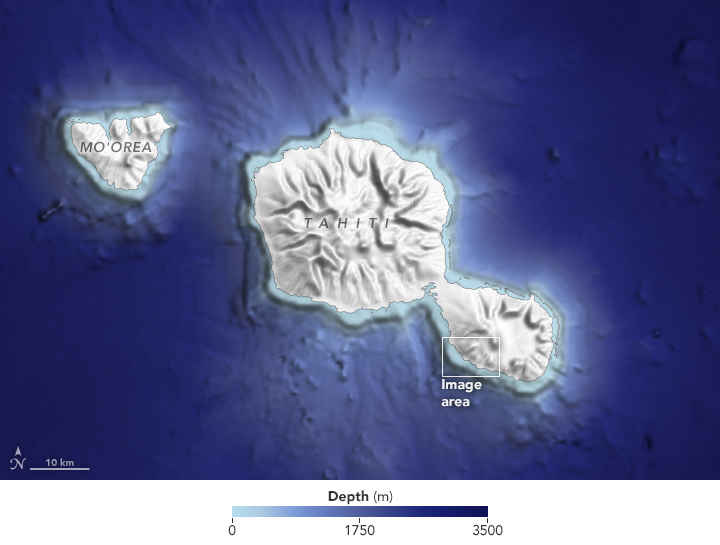

On May 2, 2022, the Operational Land Imager-2 (OLI) on Landsat 9 acquired this natural-color image of Tahiti, an island of French Polynesia. The scene falls within the timeframe—from April to October—when the waves at Teahupo’o tend to be the strongest.

Winter storms originating in the Southern Ocean and the South Indian Ocean frequently move into the southwest Pacific Ocean basin. From there, large storm-generated swells can travel unimpeded toward the southern coast of Tahiti. Swells that approach Teahupo’o from the south or southwest are perfectly aligned to produce the area’s famously powerful barrel waves.

But the legendary waves would not exist without equally perfect bathymetry. The seafloor around Tahiti rises quickly from about 5,000 feet deep at 3 miles from shore to just 1,000 feet deep at 0.3 miles from shore. As a result, southwesterly swells carry ample energy from the open ocean until they are very close to shore and crashing into the reef off Teahupo’o.

As the swells approach the reef, water piles up into a towering barrel wave; at the same time, water over the reef is pulled away from the shore. Surfers are actually below sea level as they ride—and dangerously close to the reef—until entering the lagoon closer to shore. A deep channel to the west, along with a deep slot in the reef, can focus even more energy into the barreling waves.

The epic waves at Teahupo’o have drawn participants to numerous surfing competitions, and the International Olympic Committee approved the site as the surfing venue for the 2024 Paris Olympic Games. Teahupo’o is about 9,700 miles (15,000 kilometers) from France, one of the longest distances between an Olympic medal event and the host city.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey, topographic data from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) and bathymetry data from the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO). Story by Kathryn Hansen.

The waves off the coast of Teahupo’o can heave a crushing amount of water toward the shore and onto unlucky surfers.

Image of the Day for July 14, 2022