When farmers in Ukraine planted wheat, canola, barley, and rye in autumn 2021, their concerns were relatively routine: would dry weather or rising fertilizer prices cut into their yields and profits? By the time those winter crops emerged from dormancy in spring 2022, life in Ukraine had turned completely upside down.

Russia had invaded. The war sent tanks rolling through fields, covered farmland with mines, and rained artillery shells on crops. Fuel and fertilizer prices soared. Labor became scarce. Some farmers left to join the fighting; others died or fled as their villages were bombarded. Even farmers far from the front lines watched tens of millions of tons of grain and other agricultural goods sit idle in silos and ports due to a naval blockade. As the war dragged on, even grain and vegetable oil storage facilities became targets.

“The world’s breadbasket is at war,” said Inbal Becker-Reshef, director of NASA’s Harvest program. Before the war, Ukraine provided 46 percent of global sunflower oil exports, 9 percent of the wheat exports, 17 percent of the barley, and 12 percent of the maize on global markets, according to data from the U.S. Foreign Agricultural Service. (Ukraine and Russia together accounted for 73 percent of sunflower oil exports, 33 percent of wheat, and 27 percent of barley.) The past few months have disrupted that flow of food.

“We’re in the beginning stages of a rolling food crisis that will likely affect every country and person on Earth in some way,” said Becker-Reshef. For some populations, this could mean higher prices or missing items at the grocery store. For others, history suggests it could mean more acute food shortages.

For more than a decade, Becker-Reshef and other NASA-funded scientists have been developing innovative satellite-based techniques to monitor commodity crops such as wheat and maize in Ukraine. The interdisciplinary group collects and analyzes environmental, economic, and social science data in order to improve agriculture-related decision-making around the world. With the arrival of war, such tools could play a key role in anticipating and averting food shortages and famines.

The map at the top of the page—based on data from Planet Labs satellites and the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 mission that was processed and analyzed by NASA Harvest—shows the distribution of summer and winter crops in Ukraine as of June 13, 2022. The map also shows where farmers were operating freely and where their lands were under Russian control. Roughly 22 percent of Ukraine’s farmland—including 28 percent of winter crops and 18 percent of summer crops—is under Russian control, according to NASA Harvest’s analysis. Summer crops, mainly maize and sunflower, are grown more widely in northern and western Ukraine than winter crops. (Data on land occupation comes from the Institute for the Study of War and the American Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project.)

The NASA Harvest team, with international partners from the GEO Global Agricultural Monitoring (GEOGLAM) initiative, measure multiple environmental factors—including precipitation, soil moisture, and temperature—to assess the health of crops and anticipate end-of-season yields. “After a slow start in the spring due to dry weather and a cold spell, growing conditions have been mostly favorable and the crops caught up nicely,” Becker-Reshef said.

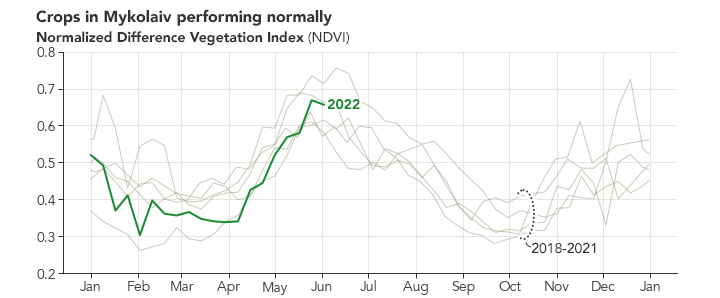

Satellite measurements of the “greenness” of crops—the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)—are important for NASA Harvest’s analysis. The chart below offers a snapshot of growing conditions in the Mykolaiv oblast, one of Ukraine’s largest producers and exporters of wheat

The researchers have also developed models, such as the Agriculture Remotely-Sensed Yield Algorithm (ARYA), that anticipate yields by blending measures of NDVI with data about environmental conditions during the growing season from NASA’s MERRA-2 reanalysis dataset. The models also incorporate detailed crop maps based on MODIS, Sentinel-2, and Landsat observations and validated by field surveys.

“Taking all of that into account, the data indicate that Ukraine is on track for a winter wheat yield of about 4.1 metric tons per hectare,” said Becker-Reshef. “That’s not quite as high as the record-breaking wheat crop in 2021, but it’s still a sizable crop given the circumstances.” The photograph below shows winter wheat near Chernihiv in June 2022.

A healthy crop in the ground, however, does not guarantee the crop will be harvested and sent to market. A naval blockade has stopped Ukraine from exporting goods by ship, halting much of the country’s ability to sell grain, explained Sergii Skakun, a NASA and University of Maryland researcher who grew up in Ukraine and spent multiple years with Ukraine’s Space Research Institute. Skakun has been studying how military conflict affected farmers and farmland in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine since fighting broke out in 2014.

“In some areas, unexploded ordnance and mines could make farming impossible in the short term,” Skakun said. “In unoccupied areas, the naval blockade of the ports and soaring fuel prices pose enormous challenges for the upcoming harvests.”

Global food prices were already rising rapidly before the war due to supply chain disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic and increasing demand for food. Despite some relief in recent months, the pace of price increases has been accelerating for several key crops, particularly cereals, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization. (Cereals includes wheat, maize, barley, and rice.) Wheat prices have risen by more than 10 percent in 2022 and have nearly doubled since 2019. Fertilizer prices have also skyrocketed, meaning farmers are likely using less of it and could see lower yields.

The months between July and October are typically some of the busiest for Ukrainian farmers. Winter crops—including wheat, barley, and canola—are ready for harvest, and spring-planted crops will also need harvesting. Next year’s winter crops must be planted by November.

“Will all of that happen this year in the middle of a war? That’s the million-dollar question,” said Skakun. “Nobody knows how this is going to play out, but I do know the NASA Harvest team will be tracking the harvest season closely. Satellites are one of the best ways to monitor Ukraine’s crops given all the dangers on the ground.”

The Landsat 8 image above shows fields of canola blooming in Mykolaiv oblast near Shyrokolanivka on May 20, 2022. Mykolaiv is Ukraine’s highest-volume port for grain, typically handling about 40 percent of exports. (Other major grain-exporting ports include Chornomorsk, Yuzhne, and Odesa.) Ships have historically carried about 97 percent of Ukraine’s grain exports, so all ports have seen sharp drops in volume this year.

“The ports are essential,” said Gary Eilerts, a NASA Harvest advisor and analyst who specializes in developing early warning systems for food shortages and famines. “Ukraine is doing what it can to export more goods via train or truck, but these other modes can only handle a small fraction of what’s sitting in the fields and will need to be harvested.”

The key to averting disruptions in the food supply will be the availability of timely data about crop prospects and about the price and distribution of key goods. NASA Harvest is working directly with Ukraine’s Ministry of Agriculture and the ESA WorldCereal consortium to help analyze crop planting, harvest, and yields. They have also developed streamlined tools—such as the Agmet Earth Observation Indicators and the Harvest2Market portal—that make relevant crop and economic data available to analysts around the world.

NASA Harvest crop data also flows to several partner organizations that monitor and respond to emerging food shortages and famines. Partners include the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), the Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS), and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

Disruptions in production and distribution of goods from Ukraine and Russia have already been a shock to the global food system. Countries already embroiled in conflict and facing serious food shortages are among the most vulnerable. Approximately 30 African, Middle Eastern, and South Asian countries—some of which are chronically food insecure—source at least 20 percent of their agricultural commodity imports from Ukraine or Russia.

“For the moment, a ‘cost of living’ crisis is more visible than a food shortage crisis in most places,” noted Eilerts in a recent blog post. But that could change if Ukraine’s goods stay out of global markets or if major cereal-producing countries have poor harvests. “We are at the beginning of what may be a long-term disruption.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using data courtesy of Inbal Becker-Reshef and Ritvik Sahajpa/University of Maryland/NASA Harvest, and Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. The NASA Harvest Ukraine 2022 Crop Classification data was produced by I. Becker-Reshef, J. Wagner, S. Baber, S. Nair, M. Hosseini, B. Barker, Y. Sadeh, S. Khabbazan, F. Li, B. Munshell, and S. Skakun at the University of Maryland and the University of Strasbourg based on data from Planet Labs and Copernicus Sentinel data. Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project provided the war zone boundaries and the ESA WorldCereal project provided cropland bounds for 2021. Photograph of winter wheat courtesy of Sergii Skakun. Video by NASA Harvest. Story by Adam Voiland.