Cracks growing across Antarctica’s Brunt Ice Shelf are poised to release an iceberg with an area about twice the size of New York City. It is not yet clear how the remaining ice shelf will respond following the break, posing an uncertain future for scientific infrastructure and a human presence on the shelf that was first established in 1955.

The cracks are apparent by comparing these images acquired with Landsat satellites. The Thematic Mapper (TM) on Landsat 5 obtained the first image (left) on January 30, 1986. The second image (right), from the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8, shows the same area on January 23, 2019.

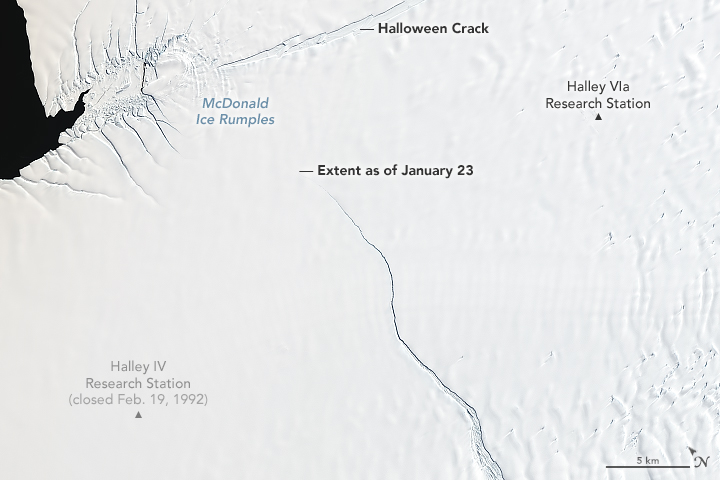

The crack along the top of the January 23 image—the so-called Halloween crack—first appeared in late October 2016 and continues to grow eastward from an area known as the McDonald Ice Rumples. The rumples are due to the way ice flows over an underwater formation, where the bedrock rises high enough to reach into the underside of the ice shelf. This rocky formation impedes the flow of ice and causes pressure waves, crevasses, and rifts to form at the surface.

The more immediate concern is the rift visible in the center of the image. Previously stable for about 35 years, this crack recently started accelerating northward as fast as 4 kilometers per year.

The detailed view shows this northward expanding rift coming within a few kilometers of the McDonald Ice Rumples and the Halloween crack. When it cuts all the way across, the area of ice lost from the shelf will likely be at least 1700 square kilometers (660 square miles). That’s not a terribly large iceberg by Antarctic standards—probably not even making the top 20 list. But it may be the largest berg to break from the Brunt Ice Shelf since observations began in 1915. Scientists are watching to see if the loss will trigger the shelf to further change and possibly become unstable or break up.

“The near-term future of Brunt Ice Shelf likely depends on where the existing rifts merge relative to the McDonald Ice Rumples,” said Joe MacGregor, a glaciologist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “If they merge upstream (south) of the McDonald Ice Rumples, then it’s possible that the ice shelf will be destabilized.”

The growing cracks have prompted safety concerns for people working on the shelf, particularly researchers at the British Antarctic Survey’s Halley Station. This major base for Earth, atmospheric, and space science research typically operates year-round, but has been closed down twice in recent years due to unpredictable changes in the ice. The station has also been rebuilt and relocated over the decades. The detailed image shows the station’s location (Halley IV) until it was closed in 1992. In 2016-2017, the Halley VI station was relocated to a safer location (Halley VIa) upstream of the growing crack.

Calving is a normal part of the life cycle of ice shelves, but the recent changes are unfamiliar in this area. The edge of the Brunt Ice Shelf has evolved slowly since Ernest Shackleton surveyed the coast in 1915, but it has been speeding up in the past several years.

“We don’t have a clear picture of what drives the shelf’s periods of advance and retreat through calving,” said NASA/UMBC glaciologist Chris Shuman. “The likely future loss of the ice on the other side of the Halloween Crack suggests that more instability is possible, with associated risk to Halley VIa.”

NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Kathryn Hansen, with image interpretation by Chris Shuman (NASA/UMBC).