Tom and I have been very busy this week, working with our team and with the folks here on station to build the infrastructure associated with our traverse platform.

A nearly complete sled. Modules from left to right: 1) sleep module; 2) cargo module; 3) fuel and generator module; 4) kitchen module; and 5) bathroom module.

We arrived at Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station about a week ago and were extremely pleased to find that the sleds for our traverse were ready for us to start rigging up our tents and gear. The folks here on station have been extremely helpful. They laid out the ‘high molecular weight’, or HMW, plastic sheets that are the foundation of our sled platform. The HWM sheets are pretty cool: they have an awesome coefficient of friction and allow for 10,000 lbs of gear to tow more like 1,000 lbs. And they are wicked slippery – you do not want to walk on this stuff. It’s much safer to walk on the surrounding ice!

A slippery HWM sled, with pallets and fuel drums.

On top of the HMW sheets of plastic, the folks here at Pole attached some special pallets that allow us to strap our gear down to plywood, as opposed to directly to the HMW plastic. Each pallet will contain things like our sleeping tents or our kitchen tent.

The pallets provide a surface area of about 8 ft by 8 ft, so we are making the most of these small spaces. Our sleeping tents (which are just run-of-the-mill mountaineering tents) barely fit on these platforms!

Tent on pallet and HMW sled.

So for added structural integrity, the tents are tied off and bolted (!) to the pallets.

Corner of a sleeping tent, bolted down.

So many folks here at Pole have been enthusiastically helpful to our project. JD, who seems to be a jack-of-all-trades, has visited our site every day and even some evenings. He’s like the South Pole Fairy, who sneaks into our site during the night and leaves exactly what we need, when we need it, including drill bits, fuel, and storage boxes. Darren the carpenter has also been out to our site nearly daily. He has been instrumental in working with our mountaineer, Forrest, to ensure that our gear (especially our tents) will travel smoothly over what might be bumpy terrain.

JD delivers cargo to our site.

By the end of this past week, given the support of folks around town, our two sleds have turned into modest living quarters, capable of withstanding the roughly three weeks of traversing on the ice sheet that lies ahead.

But just when you feel proud of your accomplishments, along comes a not-so-gentle reminder that you are just a light-weight traversing effort: The massive South Pole Traverse rolled into town, delivering fuel to the station. They passed our staging area using Caterpillar tractors, towing hard-sided sleeping and living modules.

A South Pole Traverse (SPoT) vehicle and cargo modules.

And finally, despite our best efforts, we have been slightly delayed in getting into the field. But that meant that we were able to spend Christmas here at Pole, as opposed to huddled together in our small kitchen tent, out on traverse. The station went out of its way to make folks feel warm and festive, even though we are all ~10,000 miles from home. The galley was done up special for the event and the food was simply fantastic.

Christmas dinner at South Pole.

Happy Holidays everyone! We will write again in 2018!

-Kelly and Tom

After a few extra days in the seaside town of McMurdo Station, we flew on a ski-equipped LC-130 for the sunny environs of South Pole Station, where we had a flawless touchdown on the groomed skiway next to the station. This is our last stop before embarking on the traverse in about a week. Our main objective here is to prepare our vehicles and sleds for travel, and take some cool pictures.

The team at the bottom of the world.

The Amundsen-Scott South Pole station is located right at 90 degrees south latitude (ok, maybe not exactly there, but the station is within about 100m of 90 S). It’s named for the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, who first set foot here in December of 1911, and for the British explorer Robert F. Scott, who followed closely behind in January 1912. The United States established a station here in 1957 as part of the International Geophysical Year, and it has been continuously occupied ever since. The current station, commissioned in 2008, is the third major station the U.S. Antarctic Program has built here. The prior station (the iconic geodesic dome) was disassembled and sent back to the US.

The elevated design of the station is intended to reduce snow drift, a major consideration when building structures on the ice sheet.

We are here in the height of the summer season, and there are ~150 people on station making the most of the relatively warm weather (-30 C, or -22F) for construction projects, moving cargo, and of course, science projects like ours. In winter, the station is much quieter with around 40 people spending the long winter keeping the station running.

For the first few days we’re here, our main job is to do very little. The South Pole Station sits on top of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet at about 10,000 feet above sea level, which is a big jump from the sea level McMurdo Station. The keys to acclimatization are to drink plenty of water and avoid exercise, though a little walking is fine. After about three days, we will be cleared to move on to more vigorous activities.

The 2017 geographic south pole marker.

There is a marker placed at the geographic South Pole, designed by the wintering crew at the station. Every year on January 1, the new marker is placed and the marker from the past year is put on display inside the station. Since the entire station (and skiway, and cargo, and traverse vehicles) are on top of the ice sheet, the whole station moves along with the ice. The ice shifts about 30 feet per year toward the 40 degrees west line of longitude where it eventually becomes part of the Filchner-Ronne ice shelf. (Don’t worry though, at the current velocity, it will take tens of thousands of years to get there.)

The perhaps more familiar scene is from the ceremonial south pole – a post with barbershop stripes and a reflective ball on top, surrounded by the flags of nations signing the original Antarctic treaty. The two poles are a few hundred yards apart and are both worth a visit if you find yourself down this way. Tell ‘em Tom sent you.

The team at the geographic south pole: Forrest McCarthy, Tom Neumann, Kelly Brunt, and Chad Seay.

Earlier today, we visited our cargo that we shipped from McMurdo and had a look at our sleds. It looks like everything has arrived, and as soon as our breath catches up with us, we will begin packing the sleds and pitching our tents!

-Tom and Kelly

CYGNSS was launched into low Earth orbit on December 15, 2016 at 08:37 EST and today is its first anniversary. The mission has had a very busy first year on orbit, transitioning from an early engineering commissioning phase into the science observing phase in time for the very active 2017 Atlantic hurricane season. The mission was supported during the hurricane season by the NOAA Airborne Operations Center (AOC), which operates a fleet of P-3 “hurricane hunter” airplanes that make reconnaissance flights into tropical storms and hurricanes to observe wind speed and other weather conditions first hand. We worked closely with AOC to coordinate many of their flight campaigns with overpasses of the storms by CYGNSS. They were able to time many of their eyewall penetrations to align closely in both time and space with our overpasses, which helps us train and evaluate our own wind speed measurements As a result, we now have dozens of coincident tracks of wind speed observations through the inner core regions of Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Jose and Maria. The collaboration with NOAA this summer and fall has been incredibly fruitful, and I and the CYGNSS project team are very grateful for their generous support.

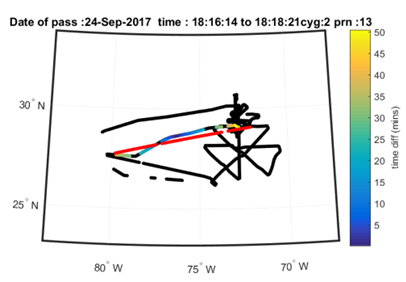

As the 2017 hurricane season winded down, we turned our attention to processing the coincident overpass data and characterizing and evaluating the performance of our wind speed measurements. One example is shown here. On September 24, 2017 at 18:13-18:21 UTC, the CYGNSS FM#2 spacecraft flew across Hurricane Maria.

The red line in the figure shows the track of the specular reflection from transmissions by the GPS PRN#13 satellite. CYGNSS makes its wind measurements along this track. The black line in the figure shows the flight path of the P-3 hurricane hunter that day. A distinctive cloverleaf pattern can be seen that results from the plane making multiple eyewall penetrations. The colored portion of the P-3 flight path is the leg closest in time and space to the CYGNSS specular point track. The color scale represents the difference in time between the CYGNSS overpass and the P-3 observing time. With such close coincidence in time and space, we hope and expect that the two measurements of wind speed will be consistent.

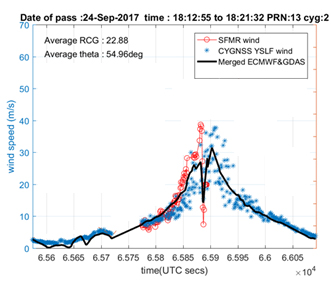

The next figure shows the wind speed measured by CYGNSS (blue), measured by the P-3 airplane using its Stepped Frequency Microwave Radiometer (SFMR) wind speed sensor (red), and produced by the ECMWF and GDAS numerical weather prediction (NWP) models (black) along the CYGNSS specular point track.

Away from the storm center at lower wind speeds, CYGNSS and NWP measurements agree well. Near the storm center, CYGNSS responds to the much higher wind speeds. In general, NWP models tend to underestimate peak winds in large storms and this is likely the case here. While NWP models generate winds everywhere, SFMR winds are only available along the portion of the satellite track where the P-3 airplane flew. In the region where coincident measurements were made, CYGNSS and SFMR winds can be seen to agree fairly well. It should be noted that the scatter present in the CYGNSS measurements can be seen to increase as the wind speed increases. This is probably a result of the decrease in GPS signal strength scattered in the specular direction when the sea surface is significantly roughened by high winds. How best to handle this characteristic of the CYGNSS wind speed retrievals will be an important topic of upcoming investigations.

Happy Birthday, CYGNSS!

p.s. and just in time for the first year anniversary of CYGNSS on orbit, new science data files using the latest (v2.0) engineering calibration and science retrieval algorithms have just been posted at the NASA PO.DAAC web site. Access the data by going to

https://podaac.jpl.nasa.gov/dataset/CYGNSS_L1_V2.0

https://podaac.jpl.nasa.gov/dataset/CYGNSS_L2_V2.0

https://podaac.jpl.nasa.gov/dataset/CYGNSS_L3_V2.0

and selecting the ‘Data Access’ tab to reach an FTP link to the data files.

Tom and I arrived in McMurdo Station, Antarctica, last Tuesday. Since then, it has been a busy week, full of specialized training and preparing to depart into the deep field…

We flew from Christchurch to McMurdo – 7.5 hours on a C-130 airplane operated by the Royal New Zealand Air Force. There were 38 passengers in the front of the aircraft and three pallets of gear in the rear. The passenger space is extremely tight; you have to work together with your neighbors to share space in an effort to remain as comfortable as possible for the long flight. And ladies, the restroom facilities are not fabulous.

Kelly and Tom on the ice runway at McMurdo Station, Antarctica (Credit: Neumann)

We landed in McMurdo on one of the nicest days that we’ve seen. It was about 25 F and sunny. Folks that had been down here before were excited to be off of the plane. And folks that had never been here before were in awe, and just wandered around on the ice tarmac, taking it all in.

The view from the runway is quite spectacular. You are standing on an ice shelf, or the edge of the ice sheet that has met a bay and is now freely floating on the ocean. In one direction, you see the full Royal Society Range and the McMurdo Dry Valleys, one of the few places on the continent where rocks are exposed through the ice. In the other direction, you see Mt Erebus, Earth’s southernmost active volcano.

Tom and Kelly at the McMurdo Station sign (Photo: Brunt)

From there, we got in a massive vehicle called Ivan the Terra Bus and headed to McMurdo Station. The driver, Shuttle Bob, is quite possibly the best greeter for any station anywhere. The ride to the station was about 15 miles and took us a little under an hour, as we moved slowly over the ice shelf. Once on station, we were given keys to our rooms, ate dinner, and went to bed. The real work started quickly the following day…

The next few days were completely full of specialized training, including tips and tricks for safe deep-field camping, altitude training, and environmental briefings, where you are reminded just how fragile this environment truly is. We have also recently received training on how to drive the PistenBullys, which are the vehicles we will be using for our traverse. These are tracked vehicles that are more commonly seen grooming ski areas in North America.

Tom and Kelly inside a PistenBully, like the one they’ll use for the traverse along 88 degrees south.

(Photo: Brunt)

Along with training, we spent a lot of time this week grabbing deep-field gear and then packing our cargo to fly to the South Pole, where we will depart on the traverse. Our cargo includes science instrumentation, vehicle parts and tools, food, and camping gear, such as tents and sleeping bags rated to -40 F. And our cargo also includes some creature comforts, such as skis and ukuleles.

Tom banding up our last bit of cargo to enter the system — this precious box contains the coffee for the traverse. (credit: Brunt)

And finally, the week has included a never-ending pursuit for a good cup of coffee. The coffee in the galley consists of ground beans that come from a can. While we did bring coffee south with us for the traverse, those beans are already in the cargo system, ready to go to the South Pole. And there isn’t a Starbucks or Dunkin Donuts anywhere to be seen. So, we found the next best thing: The McMurdo Coffee House. A team of baristas, who are officially down here with other jobs, step up to the plate and provide the community with the best coffee available on station. They work exclusively for tips and often receive cash, fresh fruit, and even mission stickers (which are somewhat like currency down here).

The McMurdo Coffee House (Photo: Brunt)

Our flight to the South Pole is scheduled for this Friday, and we are pretty much ready to go! So hopefully, next week, we will be blogging from Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. Stay tuned!

-Kelly & Tom

Greetings from New Zealand!

Soon, we’ll report back from even further south. We’re headed to the heart of the Antarctic ice sheet, to collect measurements on the ground for the ICESat-2 mission.

While NSF calls us the 88S project, sometimes you need that extra precision. We’re NASA. (Logo design by Adriana Manrique/NASA)

ICESat-2 is a NASA satellite, scheduled for launch in 2018, that will measure the height of ice sheets, glaciers, and sea ice in unprecedented detail. Designed and built at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, it will carry a laser instrument called the Advanced Topographic Laser Altimetry System (ATLAS). ATLAS will send out small pulses of laser light, and precisely time how long the light takes to travel from the instrument, down to the earth, and back. These measurements, along with the position of ICESat-2 in its orbit, and the direction ATLAS was pointing, allow us to determine the height of Earth’s surface wherever ICESat-2 goes.

But how do we know those measurements from space are correct? We take a sample of measurements on the ground, which we can check against data gathered by the satellite. Which leads us to Antarctica.

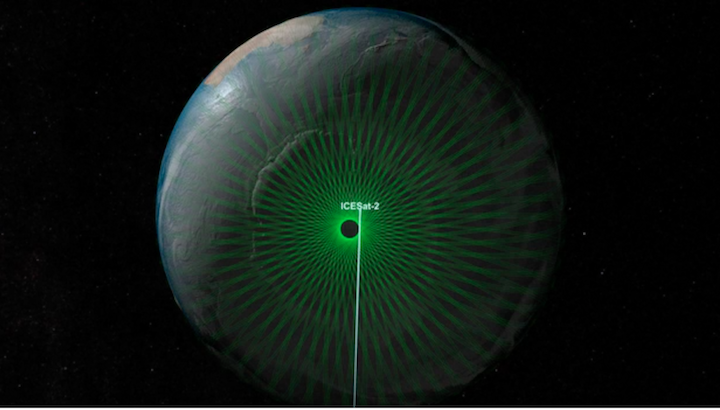

The green lines trace the path where data will be collected by the ICESat-2 mission. The tracks come closest to the poles at 88 degrees north and south, forming a dense network of crossing tracks. (NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio)

Due to the particular orbit of ICESat-2, all the tracks for the satellite converge right around a latitude of 88 degrees south. Our plan is to travel to 88S and collect measurements of the ice sheet elevation around part of the circle at that latitude. We will compare our measurements with those from ICESat-2 shortly after launch to evaluate the performance of the satellite.

Kelly and I left the US last week after months of preparation, and are now en route! The first stop on our journey is Christchurch, New Zealand, where we recalibrate our internal clocks, collect the last of our cold-weather gear, and smell the roses before heading farther south. We are traveling along with science investigators and support staff working through the Antarctic Program of the US National Science Foundation. Christchurch has been the launching point for US (and New Zealand) field work in the Antarctic for decades, and we are grateful for the support of the NSF and our colleagues here in New Zealand. It is a huge advantage to follow in the footsteps of the thousands of other Antarctic program members who have gone before us.

An array of hats, jackets, and gloves are available at the Clothing Distribution Center in Christchurch NZ to keep us warm while we’re down “on the ice.”

As you might imagine, it’ll be cold where we are headed, and having the right clothing is critical. Today, we visited the Clothing Distribution Center to borrow gloves, hats, parkas, and other items to keep us warm and safe. Tomorrow morning, bright and early, we’ll return to the CDC, get kitted up, and head south for McMurdo Station, the U.S. hub of operations in Antarctica.

Fingers crossed, and we’ll report next from Antarctica!

-Tom Neumann and Kelly Brunt