As a child growing up in Rhode Island, Katharine Johnson would run through the woods and wonder about how things used to be. She would see old apple trees or remnants of stone walls and wonder: “What used to be here? How did this place look?”

Today, her work focuses on uncovering such hidden remnants of the past. Using lidar imaging, Johnson and her colleagues at the University of Connecticut (UConn) have been piercing dense forest cover to uncover historic sites in New England.

Many of the tree-covered landscapes of modern New England were not always so green. In the 17th century, the region was the site of widespread deforestation, as European colonists built farms and homesteads. Between 60 to 80 percent of the land was cleared for fields, pastures, and orchards; these were surrounded with stone walls, houses, outbuildings, and roads.

But in the 19th century, when the United States began to industrialize and expand westward, many farms were abandoned by northeasterners who moved to cities in search of factory jobs. Around 1845, Henry David Thoreau described the decline of New England farming: “Now only a dent in the earth marks the site of most of these human dwellings; sometimes the well-dent where a spring oozed, now dry and tearless grass, or covered deep—not to be discovered till late days by accident—with a flat stone under the sod.”

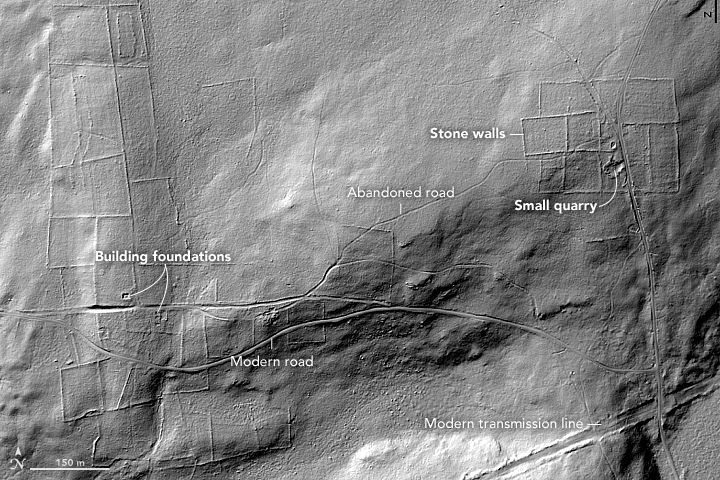

Centuries later, forests have reclaimed much of the land. The images above show the site of an early homestead in the Natchaug State Forest in Eastford, Connecticut. The natural-color photograph was shot during an aerial survey in 2012. The monochromatic light detection and ranging (lidar) image, captured in 2010, shows the same area with greater contrast and reveals features on the ground.

Lidar instruments send out rapid pulses of laser light that reflect off of solid surfaces (such as tree limbs or the ground). A receiver detects the photons that bounce back to the instrument, parsing out subtle variations in land elevation and allowing researchers to distinguish bumps and surfaces on the terrain.

Lidar has been used by archaeologists in other landscapes—perhaps most famously in Belize, where Diane and Arlen Chase have used it to uncover ancient Maya sites. Johnson and colleague Will Ouimet (UConn) started using the technology in New England to quantify the historical human impact on the landscape and how things have changed over time.

“You can see patterns people made as they were dividing the landscape and farming,” said Johnson, who is now at Earth Resources Technology, Inc. Lidar imaging helped them uncover traces of stone walls, dams, abandoned roads, building foundations, farm structures, and relict charcoal hearths—all of which have been slowly hidden over the past two centuries as the forest reclaimed the land. “The biggest surprise was being able to see the extent to which historic land use had impacted the landscape, which is not something that is readily visible in high-resolution aerial photos.”

Lidar images have been used to help preservation groups uncover several historic sites in New England. While remote-sensing technology cannot put a date on those finds—that’s where ground-based field work will come in—it has great potential to advance the field by providing a larger scale and sense of historic geography. “Lidar, coupled with geospatial analysis, gives us the ability to answer a whole range of questions that just cannot be done through traditional fieldwork,” Johnson said, “and that is what makes it special.”

To learn more about novel uses of lidar, check out Peering Through the Sands of Time, our new feature on the origins of space-based archaeology.

Images courtesy of Katharine Johnson, University of Connecticut. Story by Pola Lem and Mike Carlowicz.