HydroSHEDS’ Future |

|||

With global coverage and continued refinements, Lehner hopes that future releases of HydroSHEDS will serve a wide variety of scientific and practical applications. For example, biologists sampling fish species often use GPS (Global Positioning System) coordinates to locate habitats on maps. If their maps aren’t completely accurate, they might place fish in the wrong water body. That could be a serious problem if, for example, they are trying to identify rivers that support populations of threatened or endangered species. When the scientists Lehner worked with wondered whether this problem could be solved, he recalls, “Everyone said, ‘Not really. We don’t have good enough maps.’ But now they suddenly do.” Using HydroSHEDS, conservation biologists can pinpoint species habitats with unprecedented accuracy. |

|||

|

|||

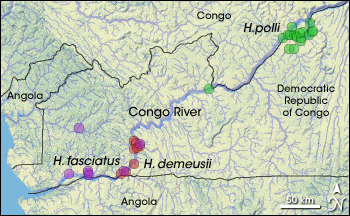

One of the scientists eager to see HydroSHEDS cover the globe is Ned Gardiner of the American Museum of Natural History, who wrote a user guide for the product. Working with the museum’s ichthyology (fish) department, Gardiner plans to use HydroSHEDS in his own research on Africa’s Congo River. “We’re looking at the evolutionary history of species,” he explains. “We know that every time we go back there, we find more fishes that seem to only be found in the Congo. There used to be a giant inland lake in Africa’s interior during the Pleistocene, but eventually the lake was captured by rivers draining to the coast.” All the fishes that evolved in the lake environment radiated into river environments over time. Though geographically separated now, they share common ancestry. Once HydroSHEDS maps for the Congo become available, museum scientists will use them to analyze river networks in conjunction with DNA data about fishes to trace their evolutionary history. |

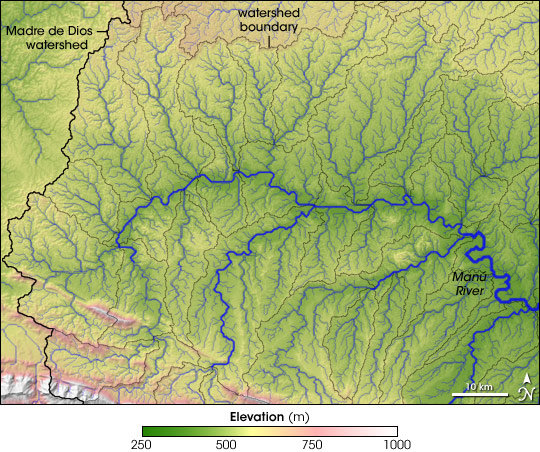

For scientists trying to collate field observations of fish with the correct rivers and streams on maps, HydroSHEDS is a huge improvement over what was available to them before. This image shows part of the Madre de Dios, with detailed information on elevation, river channels, and watershed boundaries. Elevation is color-coded, with dark green for the lowest elevation and white showing the highest. Stream channels, marked in blue-green, are overlaid on elevation data. Watershed boundaries are marked in gray. (NASA image by Jesse Allen, using HydroSHEDS data from the U.S. Geological Survey.) |

||

|

Able to live in a variety of habitats, several hundred species of cichlid fish have evolved in Africa alone, driven by rapidly changing environments. (© 2005 Lars Plougmann.) |

||

|

Today, the lower Congo River is characterized by high discharge and numerous large cataracts. Cataracts can serve as a barrier between different regions, and such barriers can increase species diversification. (© 2007 Bob Schelly, American Museum of Natural History.) |

||

|

Scientists conduct a fish species survey along the shores of the Congo. (© 2007 Bob Schelly, American Museum of Natural History.) |

||

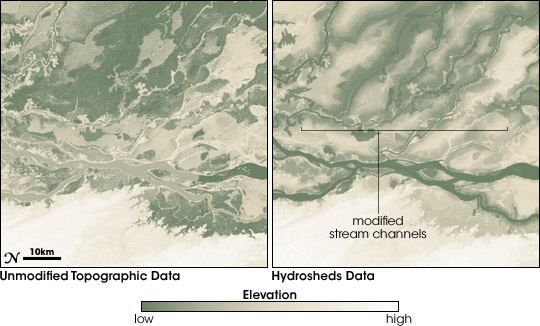

HydroSHEDS digital maps are a big step up in accuracy, completeness, and consistency for scientists and natural resource managers, but Lehner is the first to acknowledge their limitations. One is that, in pinpointing river channels based on elevation, HydroSHEDS may see rivers where there are none. In other words, it identifies potential river channels. “In a dry region like the Sahara, I still get rivers,” he explains. The product also uses vertical exaggeration. “If I detected something that looked like a valley, I lowered it, which is bad for true elevation but great for keeping the water in the channel.” To determine where channels are actually flowing with water and where they may simply be dry streambeds, the HydroSHEDS maps can be layered with other data sets, such as precipitation and soil moisture. But Lehner hopes that future releases of HydroSHEDS will contain data on actual water, in addition to water channels. |

In the Congo River watershed, many fish species that are geographically separated today share a common heritage, having radiated outward from a large lake that occupied Africa’s interior during the Ice Age. By combining fish species surveys and DNA samples with HydroSHEDS, researchers can study the evolutionary relationships of fish from different rivers. (NASA image by Jesse Allen, based on HydroSHEDS and species distribution data from Ned Gardiner, American Museum of Natural History.) |

||

|

|||

Since starting the development of HydroSHEDS, Lehner has moved on to a professorship at McGill University, but he still works closely with Abell and others at World Wildlife Fund, which will be developing the maps for the rest of the globe. Yet biodiversity isn’t Lehner’s only interest. Human water use interests him, too. According to the United Nations Environment Programme, two out of every three people may live under water-stressed conditions by 2025. As input to hydrological models, HydroSHEDS can inform decisions about human water use as well as wildlife. “At World Wildlife Fund, focus was stronger on the environment,” Lehner says, “but I don’t think I ever lost track of humans. I think they’re very equal.”

|

The creators of HydroSHEDS exaggerated small differences in elevation in raw topographic data (left). This vertical exaggeration helped the mapping software better predict potential stream and river channels (right). The digital maps can be combined with data such as soil moisture and rainfall to verify the existence of rivers and streams in different parts of the globe. (NASA image by Robert Simmon; based on data provided by Nikolai Sindorf, World Wildlife Fund.) |

||