India has been hit by a streak of unusually intense thunderstorms, dust storms, and lightning so far in 2018. The events collapsed homes, destroyed crops, and claimed the lives of over a hundred people with even more casualties, calling for assistance by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

In late April, the state of Andhra Pradesh in southeastern India was struck by about 40,000 lightning bolts in 13 hours—more than the number of strikes that occurred in the entire month of May 2017 — striking people and livestock.

On May 2, 2018, a cluster of strong thunderstorms, accompanied by strong winds and lightning, swept through the Rajasthan region in the north, knocking over large structures and harming those in the way. The potent thunderstorms whipped up one of the deadliest dust storms in decades.

One week later, the same region was hit by more deadly thunderstorms that brought lightning, 110 kilometer (65 mile) per hour winds, and violent dust storms.

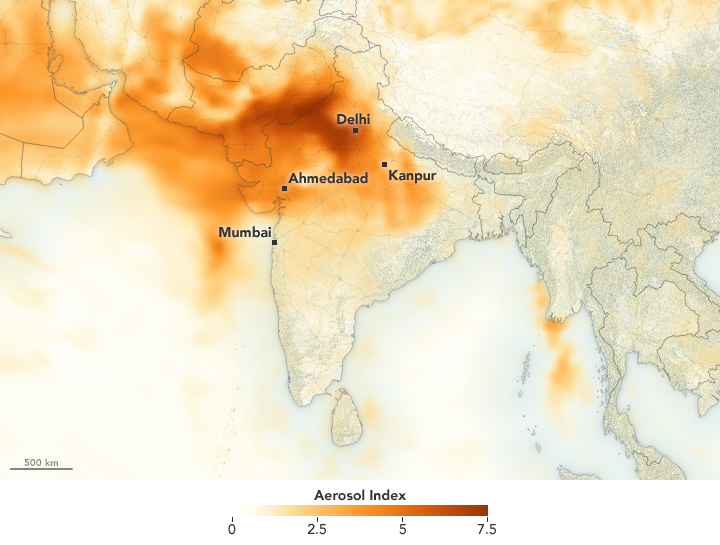

The map above shows aerosols, including dust, over northern India on May 14, 2018, around the time of the second dust storm. The aerosol measurements were recorded by the Ozone Mapping and Profiler Suite (OMPS) on the Suomi NPP satellite. The dust is naturally blocked from moving north by the Himalayan mountain range. In addition to causing accidents and poor air quality, dust aerosols can influence the amount of heat transmitted to Earth‘s surface by either scattering or absorbing incoming sunlight.

In recent years, extreme weather events such as heat waves, thunderstorms, and floods have been increasing in India, according to Ajay Singh, a climate change researcher with the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay. “Overall, the impact of global warming on the climate of India is clearly visible in the form of increased frequency and intensity of most of the extreme weather events,” said Singh.

Even with the increasing trend, the intensity of events so far this year is anomalous, said Singh. The unusual thunder and dust storms could have a combination of causes, including extra moisture from a cyclonic circulation over West Bengal colliding with destructive dusty winds. High temperatures in the area also made the atmosphere unstable, fueling thunderstorms and heavy winds.

The unusually high number of lightning strikes was caused by cold winds from the Arabian Sea colliding with warmer winds from northern India, leading to the formation of more clouds than usual. The spike in lightning this April was abnormal, but India has long been prone to lightning strikes, which are believed to cause more fatalities than any other natural hazard in the country.

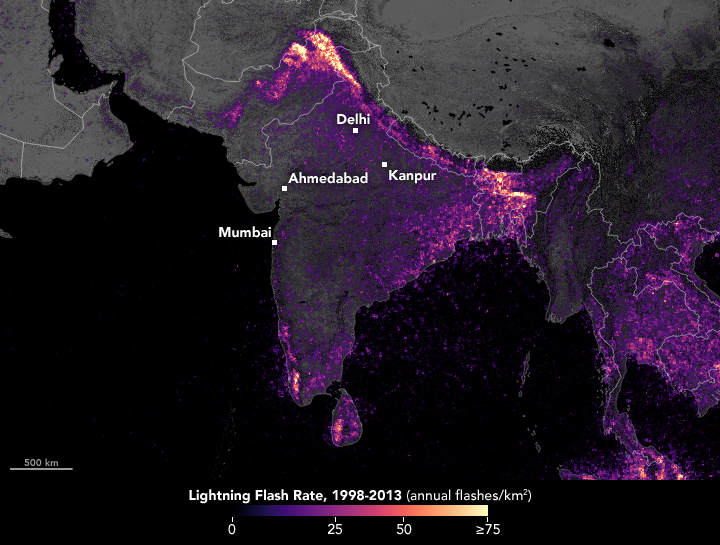

The second map shows the annual average number of lightning flashes in India from 1998–2013. The visualization was made from data acquired by the Lightning Imaging Sensor (LIS) on NASA’s Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission satellite and compiled by the Global Hydrology Resource Center (GHRC). Southeastern India usually experiences increased lightning activity before monsoon season, as heating and weather patterns become unstable and changeable.

Researchers are interested to learn how the spring 2018 lightning burst in India fits in with longer—term trends. Some years can be highly active without signaling a trend, said Dan Cecil, a scientist at NASA Marshall. For instance, a region near Andhra Pradesh had almost double the normal lightning flash rates in 2010, yet 2011 was almost exactly normal. The following years alternated between being slightly below normal and slightly above normal, according to satellite data.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using OMPS data from NASA's NPP Ozone Science Team, and lightning climatology from GHRC Lightning & Atmospheric Electricity Research. Story by Kasha Patel.