Today’s story is excerpted from our latest feature: The Rise and Fall of Africa’s Great Lake.

Lake Chad sustains people, animals, fishing, irrigation, and economic activity in west-central Africa. But in the past half century, the once-great lake has lost most of its water and now spans less than a tenth of the area it covered in the 1960s. Scientists and resource managers are concerned about the dramatic loss of fresh water that is the lifeblood of more than 30 million people.

The Chad Basin sits within the Sahel, a semiarid strip of land dividing the Sahara Desert from the humid savannas of equatorial Africa. The basin is bordered by mountain ranges and spans more than 2.4 million square kilometers of Cameroon, Nigeria, Chad, and Niger. The water level in the lake is largely controlled by the inflow from rivers, notably the Chari from the south and, seasonally, the Komodugu-Yobe from the northwest. Rainfall can also reach the lake by way of smaller tributaries and groundwater discharge.

Inflow fluctuates with the shifting patterns of rainfall associated with the West African Monsoon, making the system very sensitive to drought. Most precipitation in the Sahel falls during the peak of a short rainy season from July through September. The dry season is most intense between November and March. Years with little precipitation can wreak havoc on the water supply.

Extreme swings in Lake Chad’s water levels are not new. The lake has experienced wet and dry periods for thousands of years, according to paleoclimate research. More recently, variations in depth and extent were noted by French explorer Jean Tilho, who reported in 1910 that parts of the lake had dried up. But what is new is the way researchers are studying changes in the lake.

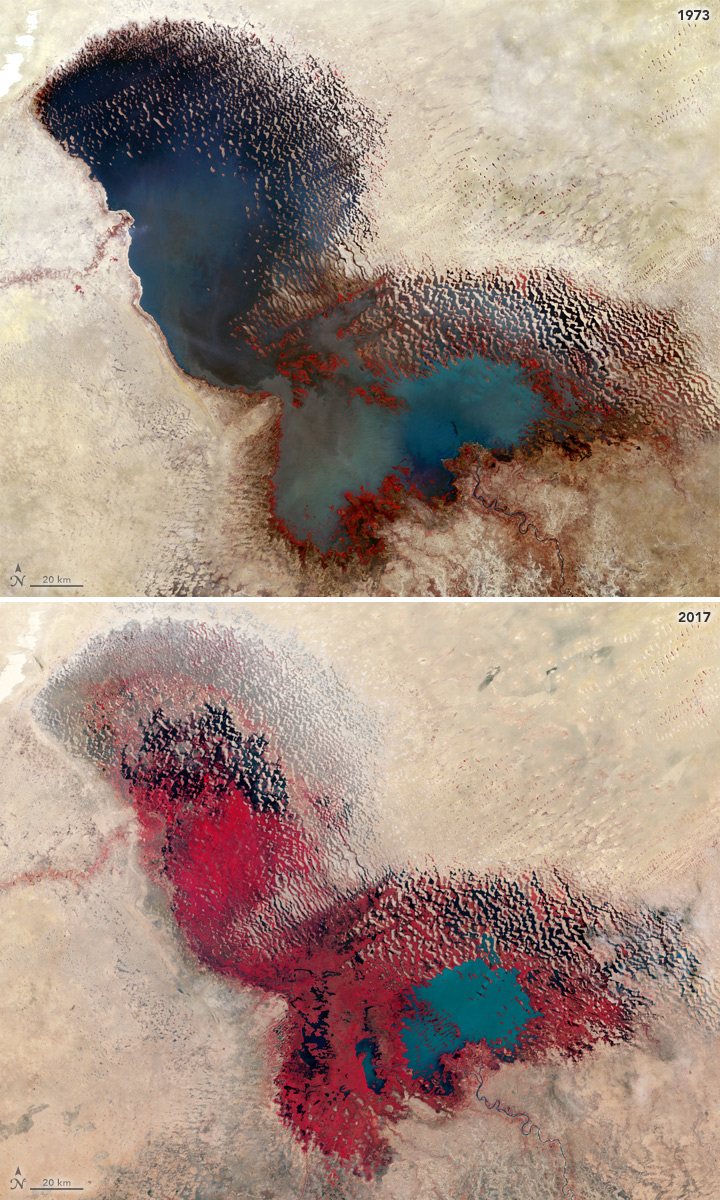

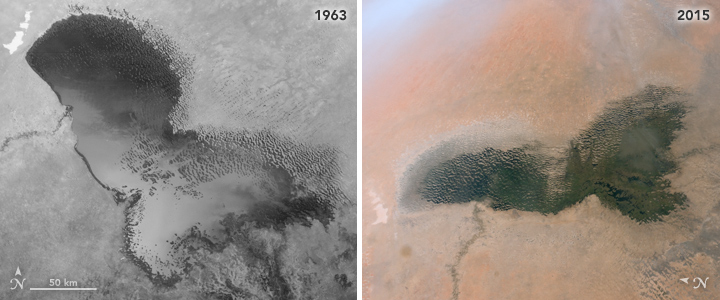

The images on this page highlight the shrinking and growing in the recent life of Lake Chad. The false-color images above were acquired by Landsat satellites—Landsat 1 in 1973 and Landsat 8 in 2017. The combination of visible and infrared light helps to better differentiate between vegetation (red) and water (blue and slate gray). The photographs below were captured by the Corona spy satellite in 1963 and by an astronaut on the International Space Station in 2015.

In 1973, the lake was in a phase called “Normal Lake Chad”—a single body of water with an archipelago on the north side of the southern basin. Note how little vegetation was around the lake at that stage. Throughout the 1970s, severe droughts plagued the African Sahel, and water disappeared from the northern basin. Since then, water has come and gone from the northern lobe depending on the year and season. But the two lobes have never reconnected into a single lake.

Learn more about how and why the lake has changed by clicking here.

NASA Earth Observatory images using Landsat data and declassified military satellite Corona data provided by the U.S. Geological Survey and Astronaut photograph ISS042-E-244403 provided by the ISS Crew Earth Observations Facility and the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, NASA JSC. Story by Kathryn Hansen.