Wildfires continued to ravage Chile’s countryside in early February 2017, weeks after they flared up in mid-January. The blazes have thwarted firefighters’ efforts to control them, with new hot spots emerging daily. Satellite data and scientific analysis suggest the fires are among the worst the country has seen in decades.

Since the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite began collecting data in 2002, fires have occurred in a fairly steady, cyclical pattern in Chile, rising during the dry season and falling during wetter months. Between 2003 and 2016, MODIS detected an average of 330 daytime fire hot spots throughout Chile during the month of January. In 2017, the number jumped tenfold.

“This is unprecedented from my perspective. The smoke plumes are huge in abundance and altitude,” said Michael Fromm, a meteorologist with the Naval Research Laboratory who has been studying satellite fire data for 15 years. “Fires have gotten much larger and much more energetic than typical for that area.”

The fires left a massive burn scar near Empedrado, Chile. On January 24, 2017, the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on the Landsat 8 satellite acquired a false-color image (above) of scorched land flanked by actively burning fires. The image combines shortwave infrared, near-infrared, and green light (OLI bands 7-5-3) to distinguish burned area (brown) from unscarred land (green).

Smoke from the fires has been traveling hundreds to thousands of kilometers, satellite data shows. According to Santiago Gassó, an aerosol scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, the smoke has reached areas in the Central South Pacific, which is unusual.

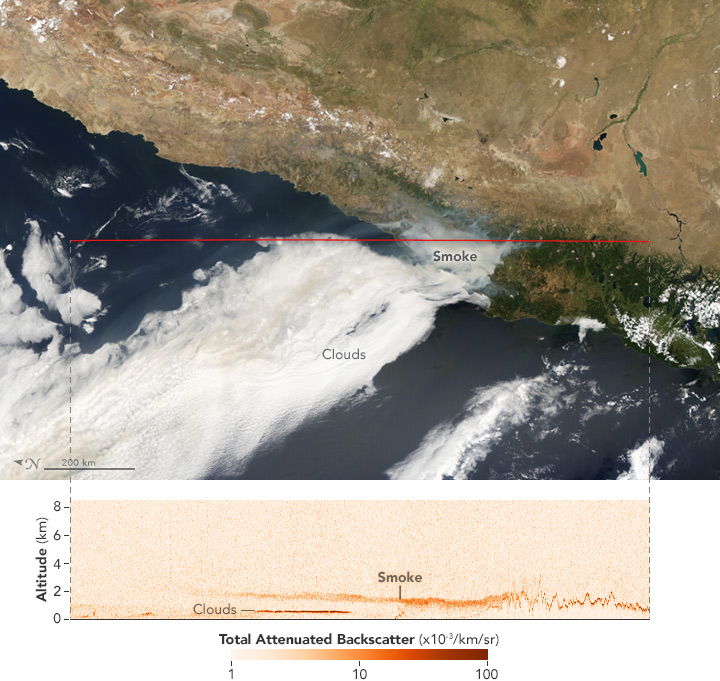

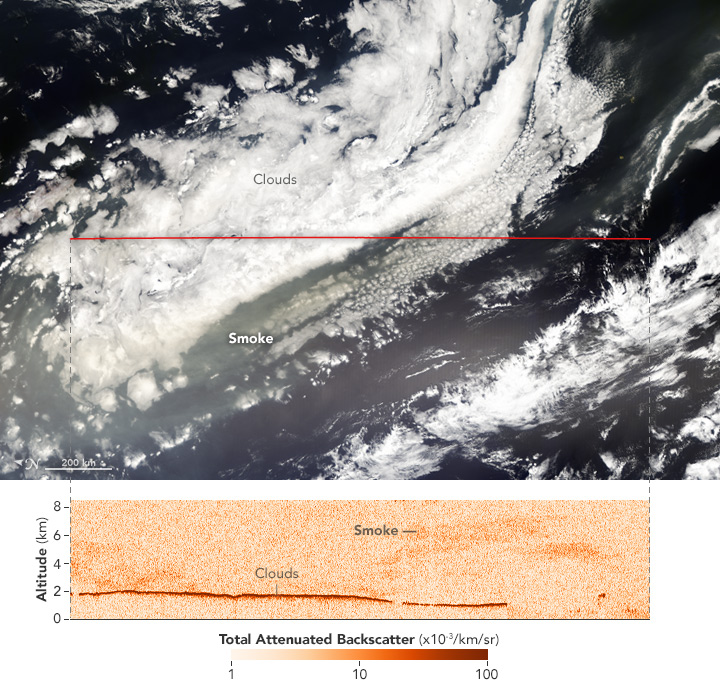

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite captured natural-color images of the smoke on January 27 and 28 as it blew over central Chile and the Pacific Ocean. Smoke has a blue or brown tint compared to white clouds. The horizontal red line on each image shows the orbital track taken by the Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observations (CALIPSO), which collected data through a vertical slice of the atmosphere.

The CALIPSO profiles above show the altitude of clouds and smoke plumes. Close to the active fires, smoke rose 2 to 3 kilometers (1 to 2 miles) high, sufficient to be visible above low-altitude clouds. As it traveled downwind and over the open ocean, smoke rose to altitudes as high as 8 kilometers (5 miles).

As of late January, the fires had consumed roughly 273,000 hectares (1,060 square miles), burned several villages to the ground, and killed at least 11 people, according to news reports. The burned area continues to grow, and multiple towns remain on red alert. Other countries, as well as non-profit organizations and individuals, have donated funds to relief and fire-fighting efforts.

There were 123 active forest fires registered in Chile on February 2, 2017, according to an update by the National Forest Corporation (CONAF). Firefighters were actively fighting 51 blazes; 68 had been controlled and 12 had been extinguished.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Jesse Allen, using expediated data provided by the CALIPSO team, MODIS data from the Land Atmosphere Near real-time Capability for EOS (LANCE), and Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Caption by Pola Lem.