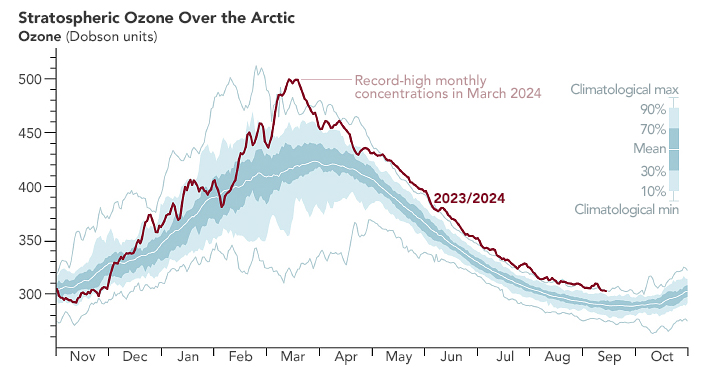

Ozone concentrations over the Arctic reached a record-high monthly average in March 2024. Due to large-scale weather systems that disturbed the upper atmosphere throughout the 2023-2024 winter, more ozone moved into and persisted in the stratosphere over the Arctic than at any other time in the satellite record.

A team of NASA and University of Leeds scientists reported their findings in a September 2024 paper in Geophysical Research Letters. “Given the absence of high Arctic ozone since the 1970s,” the authors wrote, “the March 2024 record high should be considered a positive harbinger of the future Arctic ozone layer.”

Between December 2023 and March 2024, a series of planetary-scale waves propagated upward through the atmosphere and slowed the stratospheric jet stream that circulates around the Arctic. When that happens, air from the mid-latitudes converges on the pole, sending ozone into the Arctic stratosphere. In addition to the influx of ozone, there was very little of the typical ozone depletion by substances such as chlorine, said Paul Newman, chief scientist for Earth sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and lead author of the study. “It was a very dynamical, active winter in the northern hemisphere,” he said.

More stratospheric ozone is positive for life on Earth. The stratospheric ozone layer is a natural sunscreen, absorbing harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation. The authors calculated that from April–July 2024, the UV index was 6 to 7 percent lower in the Arctic and 2 to 6 percent lower in the northern hemisphere mid-latitudes. Less UV radiation means less damage to plant DNA and a lower risk of cataracts, skin cancer, and suppressed immune systems in humans and animals.

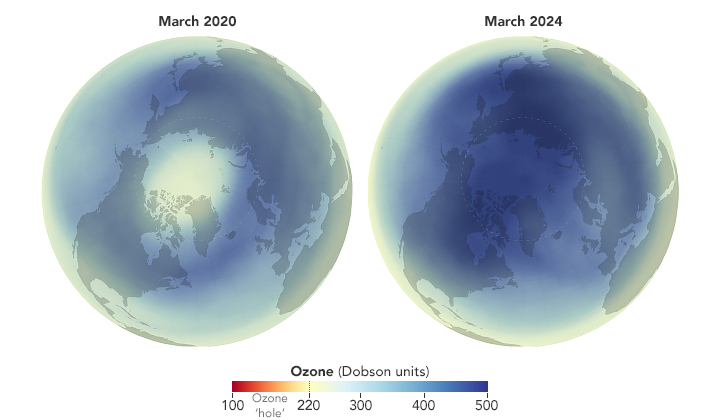

The activity in March 2024 is in sharp contrast to March 2020, when stratospheric ozone concentrations hit extremely low levels. Without disruption from upper atmospheric wave events, steady circumpolar winds prevented ozone from other latitudes from replenishing the Arctic stratosphere. The stable polar vortex also created colder-than-average conditions, favorable for ozone-depleting reactions to occur.

The maps above show ozone concentrations over the Arctic for March 2020 (left) and March 2024 (right), illustrating the large amount of variation possible there. The monthly averages were calculated by the NASA Ozone Watch team and are based on data acquired by the OMPS (Ozone Mapping Profiler Suite) on the NASA-NOAA Suomi-NPP satellite.

Unlike over Antarctica, where ozone holes form each year, the concentration of ozone over the Arctic is highly variable and subject to the “year-to-year vagaries” of tropospheric and stratospheric weather, Newman said.

The strong wave events from late December 2023 through early March 2024 resulted in the increases in ozone concentration seen in the chart above. Ozone levels peaked in March, as they typically do, and then remained well above average. May, June, July, and August also set new records for monthly average ozone concentrations. “This really is an extraordinary northern summer period,” Newman said.

As for what could have caused the unusual stratospheric weather, the authors looked at a variety of factors without finding a clear answer. The effect of climate change, for example, is difficult to quantify. “There might be a climate factor here, but it’s not obvious,” said Newman. With respect to larger atmospheric patterns such as El Niño and the Quasi-Biennial Oscillation: “Possibly, but the contribution is relatively small.”

In addition to stratospheric weather, which is the primary determinant of Arctic ozone levels, the authors think longer-term trends likely bumped ozone concentrations to record highs. Since the Montreal Protocol phased out production of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and halons in 1987, ozone levels have been slowly recovering. As such, the high March 2024 levels were within the authors’ expectations: the Goddard chemistry–climate model, GEOSCCM, showed a 1-in-8 chance of a record high by 2025, and more records are anticipated in the future. However, because CFCs persist in the atmosphere for decades, average Arctic ozone is not expected to return to 1980 levels until about 2045, they note.

Higher greenhouse gas concentrations in the stratosphere also accelerate ozone recovery. “This record was likely a result of decreased ozone-depleting substances and increased greenhouse gases. Otherwise, it would have been just a high year and not a record,” said Newman. “I call this year a harbinger of the future.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Michala Garrison, using data courtesy of NASA Ozone Watch. Story by Lindsey Doermann.