As the end of 2022 draws near, the Horn of Africa is experiencing the longest and most severe drought on record, threatening millions of people with starvation. Relentless drought and high food prices have undercut many people’s ability to grow crops, raise livestock, and buy food.

On November 7, 2022, a consortium of 16 international organizations issued a statement about the deteriorating food security crisis in Somalia, Kenya, and Ethiopia. According to the statement, large-scale loss of food and income over the past two years, due primarily to drought, has led to food insecurity for 21 million people across the region. More than 3 million people face emergency levels of food insecurity, which means they regularly go a day or more without eating and have sold their possessions to earn income for survival. In Somalia, the drought has forced over 1.3 million people to abandon their farms and migrate to displacement sites.

A combination of human-induced warming, Indian Ocean sea surface temperatures, and La Niña have contributed to four dry rainy seasons in a row, which is unprecedented in the 70-year precipitation record analyzed by researchers at the Climate Hazards Center (CHC) at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Now a fifth season of poor rainfall has arrived.

Rainfall in the Horn of Africa is concentrated in two rainy seasons: one in March-April-May and one in October-November-December. “Four dry seasons in a row is already unprecedented and now we’re in the fifth dry season,” said Chris Funk, the director of CHC. Funk contributes rainfall data and forecasts to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), a program supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and several other U.S. agencies.

FEWS NET is a collaboration between several organizations designed to monitor drought and flooding in Africa in order to identify problems in the food supply. NASA provides satellite imagery and climate, weather, and hydrologic data.

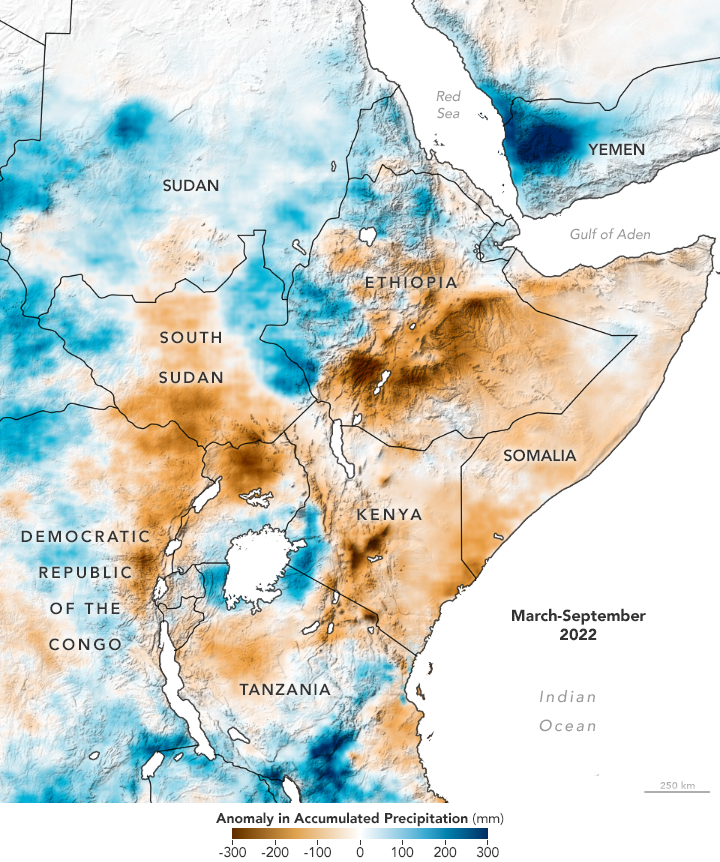

The map at the top of the page—based on the Climate Hazards Center InfraRed Precipitation with Stations (CHIRPS) dataset—shows rainfall anomalies from March to September 2022 compared to the 1981–2021 average. It shows much of Somalia, Kenya, and Ethiopia received 50 to 200 millimeters less rain than normal (about half or less of average for those months).

CHIRPS precipitation data is a key component of the FEWS NET Land Data Assimilation System (FLDAS), which NASA’s FLDAS team uses to model water supply deficits related to agricultural drought and food insecurity several months in advance. Rainfall deficits during the March-April-May 2022 rainy season were the most severe in the historic record, according to CHC researchers, and very poor rains so far in the October-November-December 2022 season has worsened the humanitarian crisis.

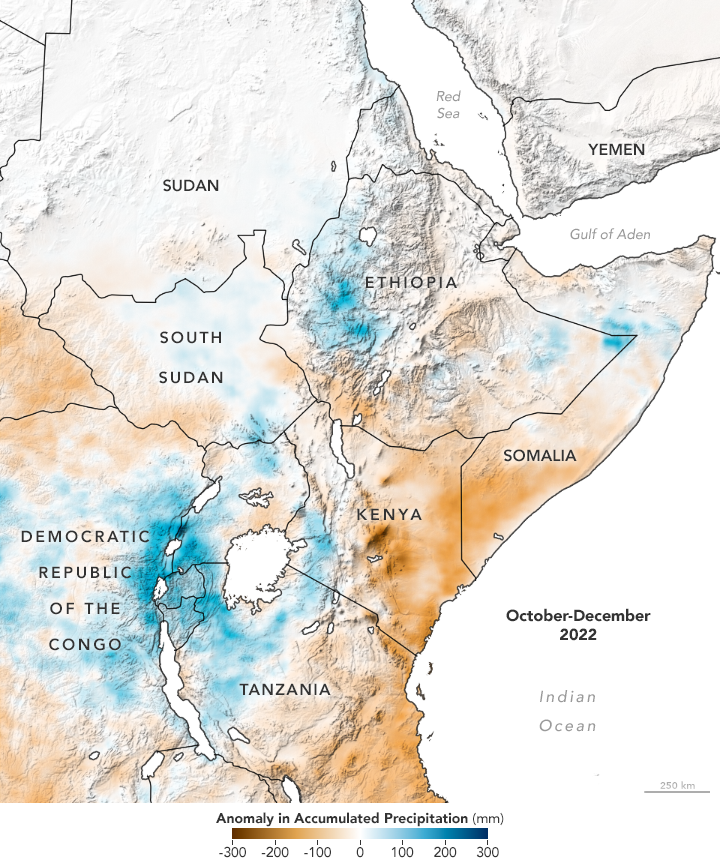

“What this region needed during October-November-December was a good rainfall season, but that’s not what happened at all,” said Laura Harrison an analyst at CHC who works with FEWS NET and the GEOGLAM Crop Monitor, a Group on Earth Observations initiative to monitor agricultural conditions and food security around the world.

CHC researchers combine CHIRPS data alongside NOAA’s weather model, the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) Global Ensemble Forecast System (GEFS), to provide 15-day forecasts of precipitation globally. This provided FEWS NET and the GEOGLAM Crop Monitor a way to get an early estimate of the drought in eastern Africa through the end of the October-November-December rainy season.

This map shows rainfall anomalies in the October-November-December 2022 season so far from the CHC early estimates. It is based on a combination of final and preliminary CHIRPS data through December 5, 2022, and forecasted 15-day CHIRPS-GEFS anomalies through December 20. The map indicates another poor-to-failed rainy season with less than normal rainfall throughout most of Somalia, Kenya, and southern Ethiopia. The drought is looking especially dire in southern Somalia and eastern Kenya, where rainfall deficits are expected to be 50 to 200 millimeters less than average in many areas, which is only 30 to 60 percent of the average rainfall.

FEWS NET analysts contribute to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), which provides a common scale for classifying the severity and magnitude of food insecurity and acute malnutrition. Famines are declared when at least one in five households faces an extreme lack of food; more than 30 percent of children under five are suffering from acute malnutrition (wasting); and at least two people out of every 10,000 are dying each day.

The latest IPC analysis projects that a famine will most likely occur among rural and displaced populations in Bay Region and Mogadishu—located in southern Somalia—between April and June 2023 if current levels of food assistance are not sustained.

“Large-scale humanitarian food and nutrition assistance has likely been the key factor that prevented an all-out famine this year,” said Lark Walters, food security analyst for FEWS NET. “Without significantly higher levels of assistance in 2023, we are extremely concerned that deaths over the course of the prolonged 2020-2023 drought could exceed that of the 2011-2012 famine in Somalia.” The drought in 2011 led to 260,000 hunger-related deaths among the Somali population.

“Our ability to monitor and predict these droughts has improved a lot,” said Funk, “as has the ability of humanitarian agencies’ ability to ingest these data.” These improvements have contributed to the prevention of famine so far this year, but the relentless lack of rain is causing the situation to deteriorate.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using data from the Climate Hazards Center, at the University of California, Santa Barbara. FEWS NET data on drought and food insecurity are available on their data portal; FLDAS data products can also be accessed through NASA’s website and the NASA Giovanni portal. Story by Emily Cassidy.