Each summer, monsoon rains sweep across southwestern Asia, soaking India and Bangladesh. In nearby Pakistan, the rains are usually less intense, more intermittent, and centered in the northeast.

Flooding forced millions of Pakistanis to flee their homes in July and August 2010. (Photograph ©2010 Abdul Majeed Goraya/IRIN.)

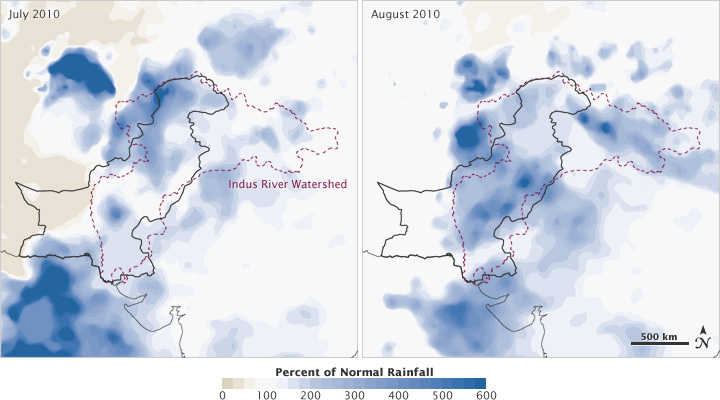

The summer of 2010 was different. In July and August, rain fell over most of Pakistan and persisted in some places for weeks. The Pakistan Meteorological Department reported nationwide rain totals 70 percent above normal in July and 102 percent above normal in August.

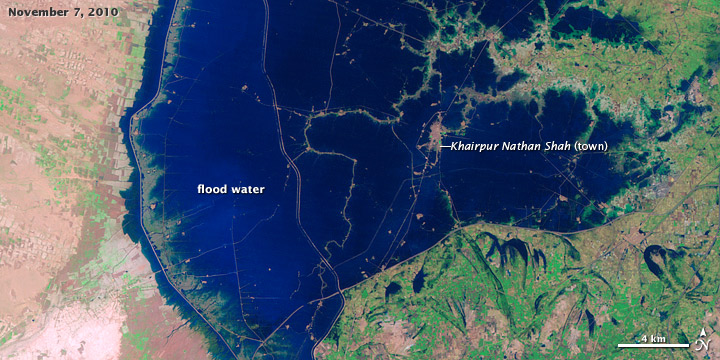

Rivers rose rapidly, and the Indus and its tributaries in the northern part of the country soon pushed over their banks. As the surge of water moved south, it swelled the Indus in Pakistan’s central and southern provinces. Then the problems started compounding. In Sindh, a dam failure sent the river streaming down an alternative channel west of the valley. The resulting floodwater lake—which merged with existing Manchhar Lake—spread over hundreds of square kilometers.

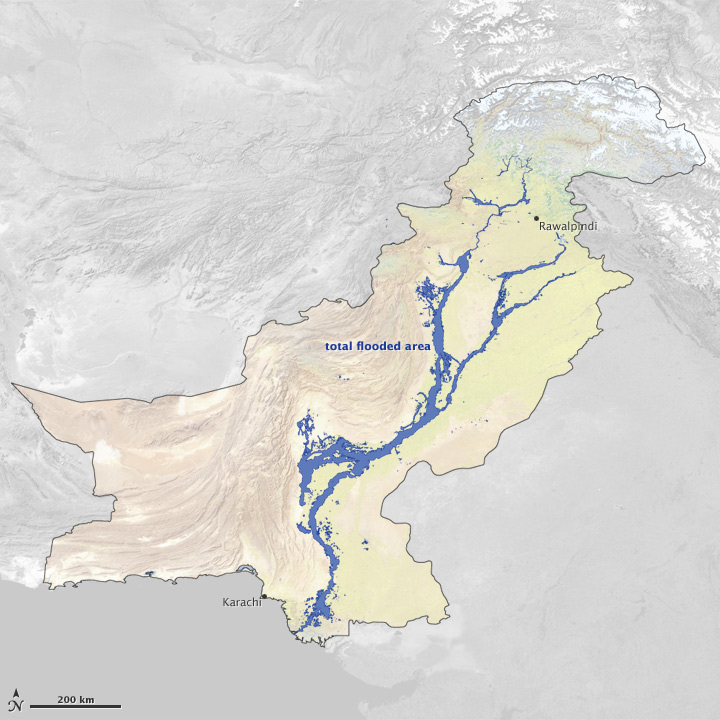

Floods covered at least 37,280 square kilometers (14,390 square miles) of Pakistan at some time between July 28 and September 16, 2010. Relief agencies used maps derived from satellite data to direct aid to many of the victims and to plan recovery efforts. (Map by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, using data from UNOSAT.)

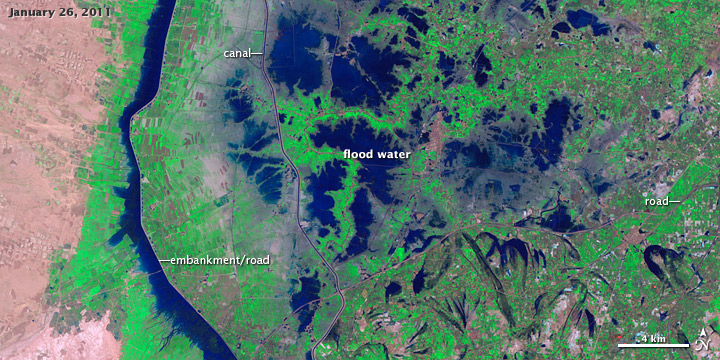

Even after the monsoon rains subsided, waters retreated much more slowly than they had advanced. Months after the rains stopped, crops, homes, businesses, and entire towns were still submerged. In some places, there were few means of water dispersal beyond waiting for it to evaporate.

The U.S. Agency for International Development estimates that the Pakistan floods affected more than 18 million people, caused 1,985 deaths, and damaged or destroyed 1.7 million houses. It was perhaps the worst flood in Pakistan’s modern history.

The Asian monsoon is one of the world’s most studied weather patterns. Sunlight warms the land surfaces of Central Asia, and the warm surface air rises into the atmosphere. This updraft draws in cooler, moister air from over the Indian Ocean. The Himalayas supercharge this convection process by blocking air masses from migrating into central Asia. Instead, the moist air masses rise, cool, and condense the water into rain.

In 2010, this pattern went awry over Pakistan. Over and over again, the rainstorms dwarfed the heaviest rainfall events from the previous, more typical summer. July rainfall in Peshawar, for instance, was up 772 percent from normal, according to the Pakistan Meteorological Department. August rainfall in Khanpur was up 1,483 percent.

The 2010 floods in Pakistan were caused by extremely high rainfall in the Indus River watershed during July and August. These maps show the satellite estimates of the difference in rainfall between 2010 and the long-term average for the region. (Maps by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, using data from the Global Precipitation Climatology Project.)

The relentless rain had a handful of causes. For one, the global La Niña event—which drenched Australia and other Pacific and Indian Ocean locations in late 2010 and early 2011—actually started around the time of the 2010 monsoon. La Niña warms both water and air masses, increasing the amount of moisture that can be carried in the atmosphere.

While La Niña increased the chance of rain events, it did not necessarily increase the intensity and unusual persistence. Instead, some meteorologists speculated in late 2010 that the jet stream might have set the stage for floods in Pakistan, as well as the summer of drought and fire in Russia. Some noted in science meetings that the jet stream had taken on an unusual pattern, stretching down over the Eurasian continent and stagnating the weather patterns.

A long-lived high-pressure system north of the Black Sea trapped hot air over Russia in 2010, and triggered heavy rainfall over Pakistan. This image shows water vapor in the atmosphere (left) and thermal infrared emissions of the Earth (right). Water is bright in the left image; on the right, dark areas are hot (desert in mid-day) and cold areas (cloud tops) are white. The animation shows the interaction between high-level flow of water vapor and the dynamics of clouds. (NASA image by Robert Simmon, using data ©2010 EUMETSAT.)

In a subsequent study (in press) using NASA satellite data, scientists William Lau and Kyu-Myong Kim of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center found a connection between the wildfires and floods. The Russian heat wave and wildfires were associated with a large-scale, stagnant weather pattern in the atmosphere—known as a blocking event—that prevented the normal movement of weather systems from west to east. Hot, dry air masses became trapped over large parts of Russia.

The blocking also created unusual downstream vortices and wind patterns. Clockwise atmospheric circulation near the surface brought cold, dry Siberian air into the subtropics, where it clashed with the warm, moist air being transported northward with the monsoon flow. The result was torrential rain in northern Pakistan.

Although the heat wave started before the floods, both events attained maximum strength at approximately the same time. Lau’s team concluded that Pakistan’s floods were triggered by the southward penetration of upper level disturbances from the atmospheric blocking, and amplified by heating and monsoon moisture from the Bay of Bengal. La Niña conditions made the tropics more receptive by providing abundant moisture.

The high pressure system over Russia was a type of blocking event, a persistent pattern in the jet stream. This map shows areas of relatively high pressure (red) and low pressure (blue) from July 25 to August 8, 2010. The map data were derived from a reanalysis—estimates of meteorological data based on a blend of actual measurements and computer models. (Map by Jesse Allen and Mike Bosilovich, using data from MERRA.)

Most of the time Pakistan usually suffers from too little water, not too much. So were the 2010 floods a sign of things to come?

“One event by itself is not evidence of a long-term shift,” says Peter Clift, a geologist from the University of Aberdeen (Scotland) who has studied the Indian monsoon. “Floods have happened in the past without global warming.”

Still, a longer, stormier monsoon season may be part of Pakistan’s future, if current climate predictions hold true.

The heavy, persistent rain would have been a challenge for Pakistanis under any circumstance. Human activities, however, probably made them worse than nature alone could have.

Vegetation naturally reduces the risk of flooding by soaking up precipitation, so almost every time humans remove trees, shrubs, and plants from the landscape, they increase the risk of floods. Decades of deforestation in Pakistan, (PDF) particularly in the Swat Valley, have left the landscape less able to absorb moisture.

Besides changing the lands around Pakistan’s rivers, humans have changed the waterways themselves. Most of the water in the upper Indus River basin runs down from glaciers in the Himalaya and Karakoram mountain ranges. Since the flow is not always sufficient to meet the needs of people downstream, dams, levees, and channels have been built to divert water for irrigation and to hold on to the sparse precipitation that the region usually receives.

Construction—including dams, roads, and canals—can divert water from its natural path. This can exacerbate flooding, or cause water to pool in areas without an outlet, sometimes for months. (Photograph courtesy Defense Video & Imagery Distribution System.)

Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt, a social geographer at the Australian National University, notes that while many of the diversions from the Indus River probably date back to the British colonial days, increasing amounts of river water have been diverted for irrigation in recent decades. Many property owners also have erected their own embankments and levees in the name of flood protection.

The majority of this irrigation infrastructure has not necessarily been well maintained over the years, says Dath Mita of the U.S. Foreign Agricultural Service. “The Pakistan irrigation and levee system is very extensive—not just large structures lined with concrete, but also channels that farmers have dug on their own land,” he says. “A system like that needs sustained maintenance, and because of accumulation of silt deposits over the years, the channels probably had a lower capacity to move water.”

As Lahiri-Dutt wrote in September 2010:

Each human interference into a natural river system has its consequence: when excessive amounts of water are drawn out of its channel, a river channel becomes less efficient and loses its ability to quickly move the water. When levees are built along the banks, the sediments get deposited on the riverbed, which gradually rises above the surrounding plains. Not only does this enhance the flood risk, the levees standing as walls also make it difficult for the floodwater to return back into the channel once it has spilled over.

Hence, there were manmade bottlenecks where water could pool whether people wanted it or not, notes Clift. In 2010, structures that were initially ineffective in containing the surge of rainwater eventually turned out to be very effective at holding it in the wrong places.

Some parts of Pakistan remained under water for months after the rains subsided. These false-color satellite images show flood water (blue) in western Sindh province in September 2010, November 2010, and January 2011. It is apparent that roads and other infrastructure constrained the flow of flood water. (NASA images by Robert Simmon, using data from Landsat 5.)

“Flooding this severe would be hard for anybody to manage,” Clift adds. “The grim reality is that, over the long term, Pakistan is a really dry place. Most of the time, they need that water infrastructure.”

Indeed, as flooding swamped areas along the Indus River, dust storms blew through the western reaches of Pakistan and in Afghanistan.

The effects of the 2010 monsoon season in Pakistan were both immediate and lasting. Waterborne diseases such as cholera menaced flood survivors, while stagnant pools of water provided the perfect breeding conditions for malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Crowded relief camps and poor sanitation helped spread diseases such as measles.

Flood waters in Pakistan’s Sindh Province had not fully receded as late as December 2010. Some refugees had nowhere to go, so they camped by their inundated fields. (Photograph ©2010 UK Department for International Development/Russell Watkins.)

David Petley, a landslide specialist from Durham University (U.K), was already keeping an eye on the Hunza landslide when the monsoon rains provoked him to start chronicling Pakistan’s unusual monsoon.

“It is hard to remember a previous flood that has caused this type of impact over such a long period, including the way it prevented replanting and reconstruction,” Petley states. Early news reports described the floods as Pakistan’s worst since 1929, “but this event was worse by almost every measure.”

In some parts of Pakistan, especially Sindh Province, flood waters lingered for months on some of the country’s best farmland. The standing water and excess soil moisture had good and bad consequences.

Pakistan has two main growing seasons, with farmers typically growing cotton and rice from May to November (Kharif season) and wheat from November to May (Rabi season). According to estimates by the USDA Foreign Agriculture Service, almost 10 percent of the country’s cotton crop was flooded, as was about one-fifth of the rice crop. The excessively wet conditions also delayed the planting of wheat in some areas, but Pakistani farmers were able to extend cotton harvesting later in the growing season.

In areas where the floods receded, Pakistanis were quick to plant crops. These rice fields in Sindh Province were almost ready for harvest on December 7, 2010. (Photograph ©2010 UK Department for International Development/Russell Watkins.)

“The good news is that Pakistan’s staple food is wheat, and by the time the serious flood events occurred, the harvest was complete and the majority of the grain was in storage,” says Mita. This lessens the blow to national food security. “Rice is a big crop, but it’s mostly for export.” He expects the excess moisture will benefit the next wheat crop, which is heavily dependent on irrigation.

Petley notes that for many flood victims, the worst consequence was the loss of livestock, “a major asset and the source of everything from milk to biogas to the power to pull a plow.”

He also worries about where flood survivors will find materials to rebuild. The United Nations, international agencies, and the Pakistan government have rebuilt some roads and bridges and have constructed roughly 40,000 shelters for some of Pakistan’s most vulnerable victims. But in many cases, citizens scrambling to build rudimentary shelter were forced to use inferior materials, meaning they now live in houses even more vulnerable to disaster.

In early 2011, flood waters had receded considerably, though some areas remained submerged. In March, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs reported that standing water prevented many families from returning to their homes in parts of Sindh and Balochistan Provinces. Even in places where waters had completely receded, people returned not to homes and fields, but to places where those things used to be.

The losses left children especially vulnerable. In February 2011, UNICEF helicopters delivered clothes, blankets, and nutritional supplements to northwestern Pakistan amid harsh winter conditions, as damage from the 2010 flood and the 2005 earthquake had left many areas inaccessible by any other means. Meanwhile, the World Food Programme delivered food to an estimated 4.4 million people in January and February 2011, including nearly 40,000 malnourished children and pregnant or nursing mothers.

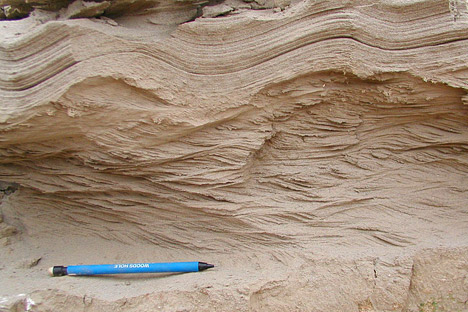

Although the 2010 floods in Pakistan were an unprecedented human tragedy, floods of similar extent have occurred in the past along the Indus. This photograph shows sand deposited by previous monsoon floods near Thatta, in southern Pakistan. (Photograph ©2004 Peter Clift, University of Aberdeen.)

Massive floods may seem rare on human time scales, but not on the geological calendar, notes Clift. He has studied the Asian monsoon and its history near the Indus, where he has uncovered buried layers of sandy sediment that was deposited by ancient floods. “We know that floods are not really common,” he notes, “but they’re not completely unusual either.”

“Still, I’ve not seen anything like this.”