The effects of the 2010 monsoon season in Pakistan were both immediate and lasting. Waterborne diseases such as cholera menaced flood survivors, while stagnant pools of water provided the perfect breeding conditions for malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Crowded relief camps and poor sanitation helped spread diseases such as measles.

Flood waters in Pakistan’s Sindh Province had not fully receded as late as December 2010. Some refugees had nowhere to go, so they camped by their inundated fields. (Photograph ©2010 UK Department for International Development/Russell Watkins.)

David Petley, a landslide specialist from Durham University (U.K), was already keeping an eye on the Hunza landslide when the monsoon rains provoked him to start chronicling Pakistan’s unusual monsoon.

“It is hard to remember a previous flood that has caused this type of impact over such a long period, including the way it prevented replanting and reconstruction,” Petley states. Early news reports described the floods as Pakistan’s worst since 1929, “but this event was worse by almost every measure.”

In some parts of Pakistan, especially Sindh Province, flood waters lingered for months on some of the country’s best farmland. The standing water and excess soil moisture had good and bad consequences.

Pakistan has two main growing seasons, with farmers typically growing cotton and rice from May to November (Kharif season) and wheat from November to May (Rabi season). According to estimates by the USDA Foreign Agriculture Service, almost 10 percent of the country’s cotton crop was flooded, as was about one-fifth of the rice crop. The excessively wet conditions also delayed the planting of wheat in some areas, but Pakistani farmers were able to extend cotton harvesting later in the growing season.

In areas where the floods receded, Pakistanis were quick to plant crops. These rice fields in Sindh Province were almost ready for harvest on December 7, 2010. (Photograph ©2010 UK Department for International Development/Russell Watkins.)

“The good news is that Pakistan’s staple food is wheat, and by the time the serious flood events occurred, the harvest was complete and the majority of the grain was in storage,” says Mita. This lessens the blow to national food security. “Rice is a big crop, but it’s mostly for export.” He expects the excess moisture will benefit the next wheat crop, which is heavily dependent on irrigation.

Petley notes that for many flood victims, the worst consequence was the loss of livestock, “a major asset and the source of everything from milk to biogas to the power to pull a plow.”

He also worries about where flood survivors will find materials to rebuild. The United Nations, international agencies, and the Pakistan government have rebuilt some roads and bridges and have constructed roughly 40,000 shelters for some of Pakistan’s most vulnerable victims. But in many cases, citizens scrambling to build rudimentary shelter were forced to use inferior materials, meaning they now live in houses even more vulnerable to disaster.

In early 2011, flood waters had receded considerably, though some areas remained submerged. In March, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs reported that standing water prevented many families from returning to their homes in parts of Sindh and Balochistan Provinces. Even in places where waters had completely receded, people returned not to homes and fields, but to places where those things used to be.

The losses left children especially vulnerable. In February 2011, UNICEF helicopters delivered clothes, blankets, and nutritional supplements to northwestern Pakistan amid harsh winter conditions, as damage from the 2010 flood and the 2005 earthquake had left many areas inaccessible by any other means. Meanwhile, the World Food Programme delivered food to an estimated 4.4 million people in January and February 2011, including nearly 40,000 malnourished children and pregnant or nursing mothers.

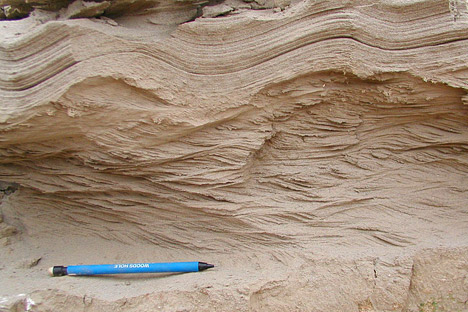

Although the 2010 floods in Pakistan were an unprecedented human tragedy, floods of similar extent have occurred in the past along the Indus. This photograph shows sand deposited by previous monsoon floods near Thatta, in southern Pakistan. (Photograph ©2004 Peter Clift, University of Aberdeen.)

Massive floods may seem rare on human time scales, but not on the geological calendar, notes Clift. He has studied the Asian monsoon and its history near the Indus, where he has uncovered buried layers of sandy sediment that was deposited by ancient floods. “We know that floods are not really common,” he notes, “but they’re not completely unusual either.”

“Still, I’ve not seen anything like this.”