|

|||

|

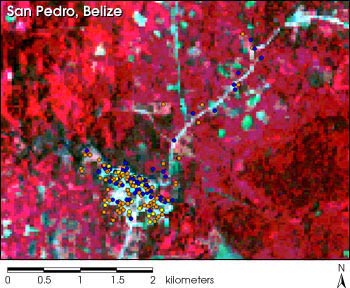

January 6, 2000 In a cluttered lab, surrounded by plastic containers fraught with hovering mosquitoes, epidemiologist Don Roberts pointed to a small, beat-up slide projector. The picture on the screen appeared to be nothing special — a satellite photo of a village littered with blue, orange, and yellow dots. Yet, for Roberts and anyone who knows his work, this image represents one of the largest health problems in the world as well as a possible solution. He explained the photo was of a typical village in Belize. Most of the houses there have dirt floors and thatched roofs. The people are extremely poor and bathe and wash their clothes in the river. And for the last ten years, at least, they have been hit with periodic malaria outbreaks that sap their livelihoods. The reason malaria is so bad in these villages, Roberts said, is that the no one in Belize has the resources to combat the problem. Using methods available today, the government would have to send people out into the countryside every six months and spray nearly every house with insecticide to keep the disease at bay. Like most third world countries with chronic malaria, they simply do not have the budget. However, the key to this problem may lie in the yellow dots on the photograph. "Over fifty percent of malaria cases in this village are represented by those yellow dots. As you can see there aren't many," said Roberts. "Less than fifteen percent of the houses." By spraying just these houses with insecticide that repels the mosquitoes, the village could rid itself of over half of its malaria problem. He said this slide represents a pattern all over Belize and perhaps the rest of the world. For the past fifteen years Roberts and a group of scientists at the Uniformed

Services University and NASA have been working on a system to pinpoint houses and

areas at high risk for the disease. Using medical databases of malaria, airplane

photographs, and even remote sensing satellites, they have laid the groundwork

for the system. By predicting this risk, the cost of spraying houses and

the amount of chemicals used in any given country would both drop dramatically.

Yet, efforts to ban spraying may prevent him or these countries from ever getting

a chance. |

A Mayan household in Belize, Central America. In tropical and subtropical regions around the world, most of them poor, malaria has again become a major killer. Research using remote sensing data by scientists at the United States Uniformed Health Services promises to reduce the threat of this resurgent disease.

| ||

The data used in this study are available in one or more of NASA's Earth Science Data Centers. |

This image taken over San Pedro, Belize, by a Landsat satellite, shows the distribution of malaria cases in the area. The yellow and orange dots show where most outbreaks occurred per household. The vegetation in the surrounding countryside is colored red in this image, while human settlements and roads are light blue. (Image courtesy Uniformed Health Services) | ||