The nighttime views collected by the day-night band are already proving useful to meteorologists and atmospheric scientists, who have been observing the dynamics of storms such as hurricanes Isaac and Sandy.

“Having the ability to see at night also helps identify features that could be missed by the other satellite sensors,” says Straka. “We can bring out things like thin plumes of smoke, low-level volcanic ash, areas of fog and other features that otherwise would blend in with the background.”

Chris Elvidge is particularly interested in the view of combustion sources — such as wildfires and gas flares — which glow in different wavelengths than manmade lights. His team can distinguish between the two by simultaneously using visible light and short-wave infrared bands. “We’re detecting much smaller gas flares with VIIRS than we could with DMSP, and we’re able to estimate the temperature and the total radiant output.” Elvidge hopes the measurements could eventually lead to better estimates of carbon dioxide emissions.

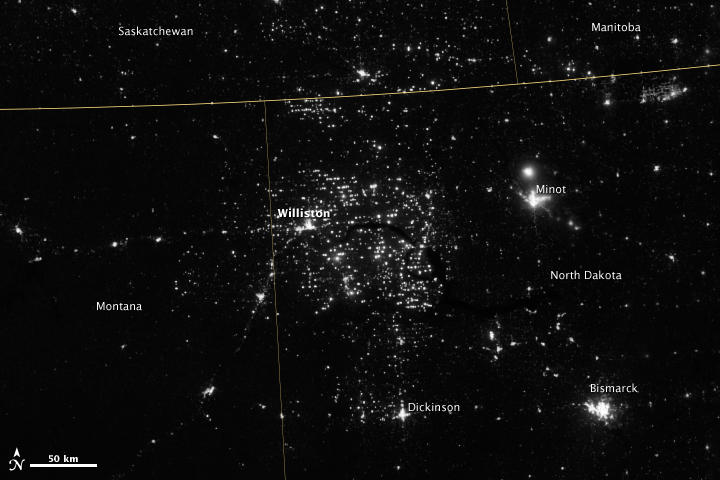

Northwestern North Dakota, one of the least-densely populated parts of the U.S., has been aglow at night in recent years. The light comes from oil drilling and gas flaring in the Bakken shale formation. (View Large Image - NASA Earth Observatory and NOAA National Geophysical Data Center)

But the most popular and poignant use of night-lights imagery remains the study — scientific and aesthetic — of city lights. “Nighttime imagery provides an intuitively graspable view of our planet,” says William Stefanov, senior remote sensing scientist for the International Space Station program office.

“City lights provide a fairly straightforward means to map urban versus rural areas, and to show where the major population centers are and where they are not,” Stefanov notes. “They are also an excellent means to track urban and suburban growth, which feeds into planning for energy use and urban hazards, for studying urban heat islands, and for initializing climate models.”

Elvidge has seen dozens of different uses for city lights imagery. “Artificial lighting is a excellent remote sensing observable and proxy for human activity.”

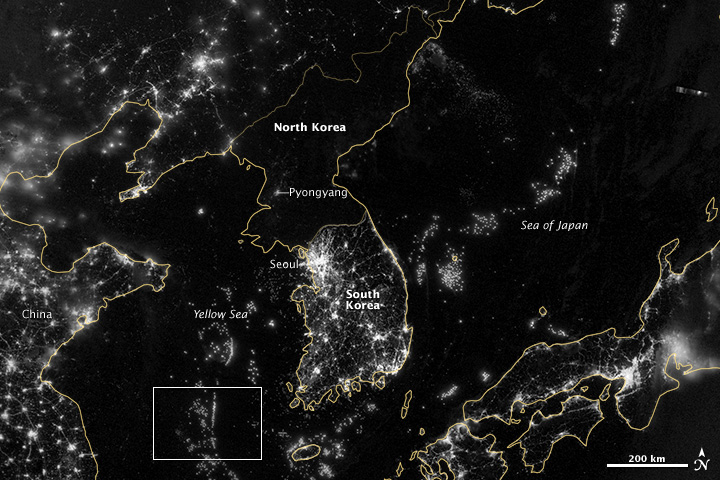

City lights are usually an indicator of where people live, but not on the Korean Peninsula. South Korea’s population is roughly 49 million and the land teems with light. North Korea has 24 million people and hardly any lights beyond Pyongyang. Offshore, the seas glow with the light of hundreds of fishing boats lining up along invisible borders. (View Large Image - NASA Earth Observatory and NOAA National Geophysical Data Center)

Social scientists and demographers have used it to model the spatial distribution of economic activity, of constructed surfaces, and of populations. Planners and environmental groups have used maps of lights to select sites for astronomical observatories and to monitor human development around parks and wildlife refuges. Electric power companies, emergency managers, and news media turn to night lights to observe blackouts.

Elvidge’s research group has been approached by groups seeking to model the distribution of carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels and to monitor the activity of commercial fishing fleets, who light up the seas to increase their catch. Biologists have examined how urban growth has fragmented animal habitat. He even learned once of a study of dictatorships in various parts of the world and how nighttime lights had a tendency to expand in the dictator’s hometown or province.

In recent years, Miller, Elvidge, and colleagues have come across unexpected applications for these “dark side” measurements, including the first satellite observations of the mysterious milky seas — the bioluminescence of maritime lore, which causes vast expanses of ocean to glow. And the unanticipated capability of the day-night band to detect reflected airglow and starlight suggests that scientists may never have to be without a visible light measurement, even on nights without moonlight.

City light maps have been used to model the distribution of economic activity and populations, to monitor human development around parks and wildlife refuges, and to observe blackouts. (View Large Image - NASA Earth Observatory and NOAA National Geophysical Data Center)

“Nighttime light is the most interesting data that I’ve had a chance to work with in my career,” says Elvidge, who has been working with nighttime imagery since 1992. “Even after 20 years, I’m always amazed at what city light images show us about human activity.”

“Even as we look toward other planets and the very corners of the universe for the next great discovery,” Miller adds, “these nighttime observations are a humbling reminder that that there are new frontiers of discovery that still await us in our own backyard.”