|

If we had the time and knew how to listen, Nature could tell us thousands of stories about how climate change is affecting life on Earth. Every tree, every insect, every bird has something important to say on the subject. From every forest, every wetland, every ocean come more stories than there are scientists to listen. Several years ago, NASA oceanographer and amateur beekeeper Wayne Esaias realized he was overhearing one of those stories. The talk of climate change was coming from his bees. Much of the science we hear about—brought to us by schoolbooks or 10-second blurbs on the radio or TV news—are stories whose end is already known. Knowledge itself may be provisional, but the stories we hear about science often focus on what’s finished: an experiment is complete, the data are in, a result is known. But when you’re a scientist, you know that between the moment when you think “I wonder why...?” and the moment when you finally understand can lie a long stretch of time where the significance of your idea, your ability to collect the data you need to test it, and the ultimate outcome of your effort is uncertain. Biological oceanographer Wayne Esaias has been passing through one of those uncertain stretches. |

The 25-year NASA veteran has made a career studying patterns of plant growth in the world’s oceans and how they relate to climate and ecosystem change, first from ships, then from aircraft, and finally from satellites. But for the past year, he’s been preoccupied with his bee hives, which started as a family project around 1990 when his son was in the Boy Scouts. According to his honeybees, big changes are underway in Maryland forests. The most important event in the life of flowering plants and their pollinators—flowering itself—is happening much earlier in the year than it used to. |

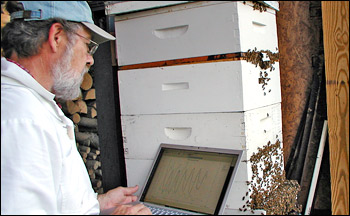

Wayne Esaias, a NASA scientist, records the weight of his beehives. Once a hobby, his beekeeping has developed into a scientific pursuit. Esaias believes that a beehive's seasonal cycle of weight gain and loss is a sensitive indicator of the impact of climate change on flowering plants. (Photograph courtesy Elaine Esaias.) | ||

|

The discovery has driven Esaias to completely remodel his ocean-centric career. He is now trying to rally financial support and scientific enthusiasm for the development of a national network of beekeepers whose hive observations can give scientists direct evidence of how climate change is affecting flowering plants and their pollinators. The information could refine predictions of the productivity of agricultural and natural ecosystems, help predict the spread of invasive species, and provide a tangible, missing link between satellite-based indicators of seasonal patterns of vegetation and the real world. |

Esaias’ honeybees are starting honey production earlier in the spring than they did when he began keeping bees in the early 1990s. In Maryland, flowering trees are the biggest nectar source for honeybees. Changes in the timing of honey production are a sign that climate change is affecting flowering trees. (NASA graph by Wayne Esaias.) | |

Whether he can pull it off is far from guaranteed. That he is willing to accept the challenges and risks of venturing outside his specialty—failing to get funding, having colleagues challenge his expertise, or discovering that the honeybee hive network doesn’t turn into the goldmine of ecological information he predicts—shows just how important he thinks the bees’ story is. |

Bees collect and deposit pollen in flowers as they harvest nectar for honey. Workers forage over an area that is similar in scale to both satellite observations of vegetation as well as ecosystem and climate models. By linking hive observations to satellite data and models, Esaias hopes to provide a better understanding of how climate change is affecting plants and their pollinators in natural and agricultural landscapes. (Photograph ©2006 John Kimbler.) | ||