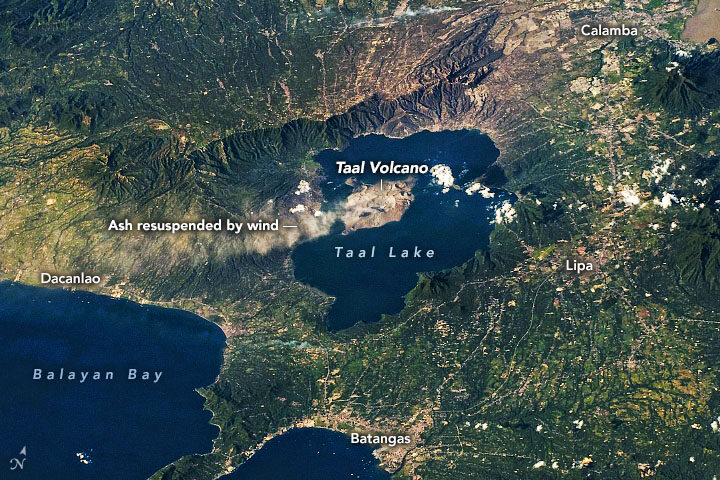

On January 12-13, 2020, Taal Volcano erupted for the first time in more than four decades. On January 22, ash plumes again emanated from Taal—but, this time, not from an eruption (seen above). According to the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS), strong low-level winds lifted previously deposited ash lying around the volcano to heights of 5,800 meters (19,000 feet).

“Resuspension of volcanic ash is more likely at higher wind speeds, if the ash is dry and if ash particles are small,” said Simon Carn, volcanologist at Michigan Tech. “The ash deposits at Taal may have initially been quite wet, so the fact that ash resuspension is now occurring may indicate that the deposits have dried out.” The Philippines is currently in its dry season.

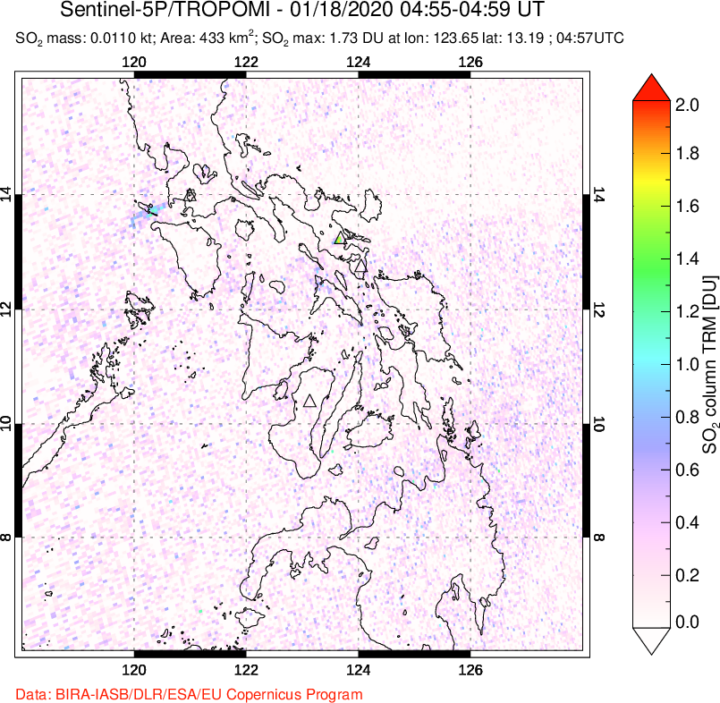

This time it was resuspended ash, but officials are cautious about a potential eruption again. Since its initial eruption, Taal remains on a level 4 alert, with a hazardous eruption still possible. Data show that SO₂ emissions, one of the key parameters for monitoring active volcanoes, have been present, but low, since the initial eruption. Carn said this indicates magma is most likely intruding into the main portion of the volcano, but predicting whether the magma will ultimately erupt is challenging.

If the volcano erupts again, it could look different than the early January event. During that “wet” eruption, water from the nearby crater lake covered the ash particles with water droplets. Wetter eruptions tend to produce finer ash particles. However, nearly all of the water in the main crater is now gone. According to Carn, the lake could have vaporized from the heat of the emanating magma; some could have been physically ejected by the previous eruption; and some could have drained through fractures or fissures in the volcano. In the absence of water, this volcano could produce a “dry” eruption, which would make comparatively larger ash particles.