NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Cultivated desert. Photo by Ragab Hafiez.

In early March 2017, we featured the top image as our monthly satellite puzzler and as an Image of the Day. But sometimes we learn even more about an image after we publish, as people write to us with a local or personal connection to the place. That was the case here.

Local knowledge is especially important when it comes to agriculture. Ragab Hafiez, a hydrogeologist and geologist working for DASCO, studies Egypt’s Western Desert. He gave us permission to re-publish some of his photographs showing the ground-based view of East Owinat, one of Egypt’s land reclamation projects aimed at making some desert areas suitable for agriculture. He also took the time to answer some questions about the satellite image that inspired the puzzler.

Q: What features visible in these images strike you as interesting?

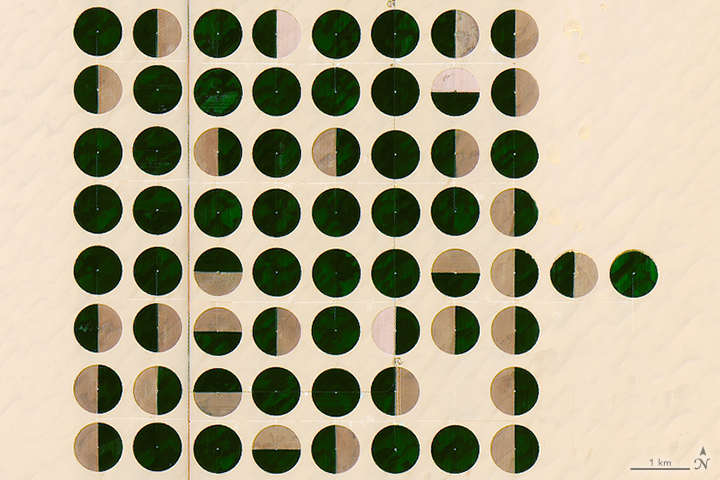

A: The features visible in these images are the irrigated crops mainly clustered in a center-pivot irrigation systems; the diameter of the pivots range from 700 to 820 meters. The total irrigated area at the beginning of this year was about 79,000 hectares.

Q: Is there anything not visible that is worth noting?

A: East Owinat is an interesting area located at the far south of Egypt. It’s an arid to hyper-arid area, the rainfall is nil, and fossil groundwater is the only source of water in the area.

The area is covered with a thin sheet of loose sand, followed by the thick sandstone rock bed. The sandstone beds belong to the Nubian sandstone formation deposited through the Lower Cretaceous and Jurassic periods.

The water wells in the area are usually drilled to depths of 200 to 350 meters (650 to 1150 feet) below the ground surface. The water level ranged from 30 to 60 meters (100 to 200 feet) below ground.

Q: Do you happen to know what crops are planted here, and the reason for the various green/brown patters?

A: The crops cultivated in the winter season are wheat, barley, potatoes, and alfalfa. Virgin soil, fresh water (salinity less than 700 parts per million), mild weather, and long daily sunlight hours are all factors that combine to produce high-quality and prolific crops.

The green areas are currently cultivated, while the brown areas are left without cultivation this season.

Wheat fields. Photo by Ragab Hafiez.

Potato fields in the desert. Photo by Ragab Hafiez.

Most of the time, we as humans in our life times may never be able to visit all the places that we see in a satellite image of the Earth. Nevertheless, the wish is always there, at least for a satellite imagery enthusiast like me. So whenever a person with ‘local or personal connection’ to a place in a satellite image, provides firsthand information, there is a sense of accomplishment with regard to that historical wish. Thank you Ragab Hafiez for revealing the unseen and thanks to Kathryn Hansen for sharing this awe-inspiring post in NEO.

These monthly puzzlers are a great way to pique one’s curiosity. But more than that, for me, the most important aim is to engage in a reasonable discussion with anyone who would like to understand the 5Ws (Where, What, When, Who, Why) of the satellite image and hopefully much more. I have noticed through my months of playing the EO puzzlers that often, the questions revolving around the satellite image lead to interesting answers and hours of searching on Google Earth literally! More often this generates open ended research questions with societal repercussions. In this process, there is a lot of new learning involved, which I love. There are also fun moments or call it fodder for conspiracy theorists on social media when someone comments: ‘These circles (center pivot irrigation) were created by Aliens!

There is, however, a greater perspective for my overwhelming sense of gratitude for these satellite imagery puzzlers. It is simply astounding to live in this age where one can view in real time another place on earth without being physically present there and be able to understand so much about it. This sense of relationship (for want of a better word?) to a place on earth is what I believe makes us all connected like never before in the history of human kind. Just think of the times in history when people thought the earth was flat, or reasoned that the area (a few sq. kms.) around them is all that exists as the ‘world’ or the notion that the actions in their village cannot impact another far away village. Fast forward to now, this world view has undergone a tremendous transformation. To quote a bad example, ‘the worst effects of human-made climate change are felt by those who did the least to cause it’.

It’s too bad that the Egyptians treat this irreplaceable water source as carelessly as they do the waters of the Nile.

Center pivot may be efficient, but as the picture shows watering plants that way in a hyper-arid climate ensures the maximum amount of water will be lost to evaporation.

I guess they still refuse to acknowledge that drip irrigation is the best possible method in such regions, no matter how much more land could be utilized with the same amount of water, because the method is closely identified with Israel the pioneer in that agricultural technology.

Though this could also be a result of backers with deep pockets in Saudi Arabia not caring how much Egyptian water is wasted as long as they get the food that’s grown.

All in all, this article reads more like a puff piece for Egypt courtesy of the Earthobservatory considering how it shies away from the likely controversial decisions that led to this being done.

It sort of makes a mockery of one of the goals of the Earthobservatory to highlight stories about the environment if the background if only bland, feel good details are included while all the negative is eschewed.

In the image of the “pivot circles” I notice that, assuming that the image is orientated N ~ S, that there are dark green areas, generally orientated SW ~ NE. Is this caused by a different mineralogy in the desert sand?

Dear Barry

In summer seasons, the farmers greening a have of pivot circle and leaving the rest half without cultivation to overcome the shortage of water. The dark green areas are cultivated, while the lighter is not.