While I was interviewing University of North Carolina climate scientist Wei Mei about his new research that shows a significant increase in the intensity of land-falling typhoons in the western Pacific, the strongest storm of the 2016 season (Super Typhoon Meranti) was on the verge of slamming into China after grazing Taiwan.

“Meranti fits the trend,” said Wei. “In 2016 so far, there have been six typhoons in the northwestern Pacific. Three have already made it to category 4 or 5. In the late 1970s, only about one-quarter of typhoons reached that strength. Now about half do.”

NASA Earth Observatory MODIS image of Super Typhoon Meranti.

Some meteorologists have mused that with sustained winds of 165 knots (190 miles per hour), Meranti would have been the equivalent of a Category 6 storm—if the Saffir-Simpson scale actually went that high. (It maxes out at 5). Even though Meranti only grazed southern Taiwan, it still knocked out power to 500,000 households and produced giant waves along the coast.

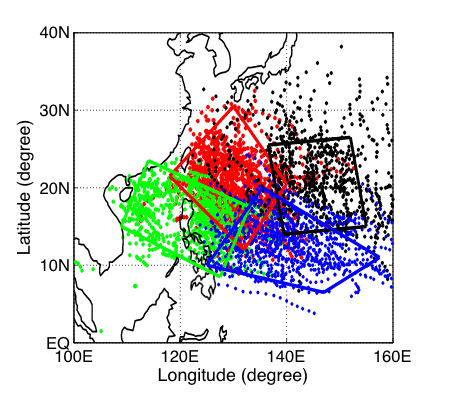

The focus of Mei’s research, however, is not Meranti or the 2016 typhoon season. Working with colleague Shang-Ping Xie of Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Mei has been digging through records that detail every typhoon in the northwestern Pacific since 1977 and looking for changes in the intensity of storms. What they found was a strong increase in typhoon intensity. Overall, landfalling storms strengthened by about 15 percent over the past four decades, with the proportion of typhoons reaching categories 4 and 5 more than doubling. Mei and Xie showed that storms that passed over waters relatively near to land and moved toward land (red and green dots in the chart below) have strengthened the most. Those that stayed out over the open ocean (black and blue dots) did not strengthen by a significant amount.

Figure from Mei and Xie, 2016.

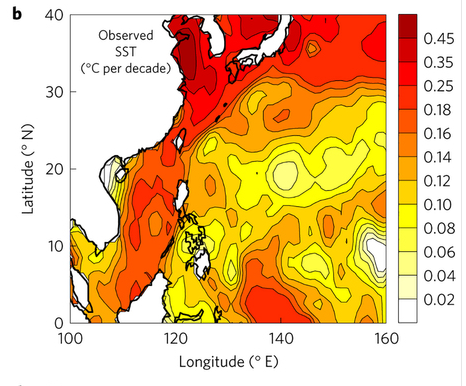

“Elevated rates of warming in coastal seas (in comparison to the open ocean) are the reason for the intensification of land-falling typhoons,” said Mei. Between 1977 and 2013, many coastal areas in Asia have warmed by upwards of 0.20 degrees Celsius (0.36 degrees Fahrenheit) per decade along the coasts—more than twice as much as open ocean areas. In the chart below, notice all the deep reds (more warming) near the coasts; farther out to sea tends to be yellow and orange (less warming).

Figure from Mei and Xie, 2016.

“We are not arguing that the warming of the coastal seas is due to greenhouse gas-driven climate change; that would require attribution studies that we have not conducted yet,” he said. “But we feel confident that land-falling storms are getting stronger because of rising sea surface temperatures, particularly in a band off the coast of East and Southeast Asia.” A related 2015 study led by Mei argued that sea surface temperatures are a more important factor in controlling long-term variations in typhoon intensity than other factors, such as vertical wind shear.

In this study, Mei and Xie did not look at the frequency of storm development. Some storm researchers have argued that a warming world may make hurricanes and typhoons stronger but less frequent.

For more details about Mei and Xie’s latest study, read more from Scripps Institution of Oceanography, The Verge, and Nature Geoscience.

Himawari-8 image of Super Typhoon Meranti and night lights (in orange) of Asia via Colorado State University and Mashable.