Some of the world’s largest companies suffered multimillion-dollar losses from flooding or drought in the past year, according to a November 16 report from The Guardian. Citing a study from the Carbon Disclosure Project, The Guardian stated that although too much or too little water can affect the profits of large companies, many of those companies remain unprepared for problems likely to arise in the future.

Natural hazards cause widespread losses in dollars and lives, but Mother Nature does not deserve all the blame. Growing human populations and increasingly expensive infrastructure have also contributed to the losses. In short, more people have more stuff for Nature to damage or destroy. For more background, see the Earth Observatory feature The Rising Cost of Natural Hazards.

[youtube 6kgU-mugZOY]

When Music and Climate Change Meet

During a recent event that highlighted the intersection of art and science, NASA climatologist Gavin Schmidt offered an intriguing pitch (see 5:15 in the video above) for a climate change symphony that would use music to tell the story of Earth’s long and varied geologic history. “There are trends in the tides of the planet that come from the changes in the continents, the wobbles in the Earth’s orbit,” he said, emphasizing Earth’s many rhythms, crescendos, and cataclysms that lend themselves to music. Schmidt’s comment came during a panel discussion that included former New York Times reporter Andy Revkin and EPA climatologist Irene Nielson, and followed a unique Antarctica-inspired performance from a string quartet arranged by Paul Miller (aka DJ Spooky). Schmidt isn’t alone in thinking along these lines. NPR recently interviewed composer Andre Gribou about creating musical scores for films shown on spherical visualization system called Science on a Sphere. A new SOS film – called Loop – came out this week.

It’s Official: 2011 Sea Ice Second Lowest on Record

A few weeks ago, the National Snow and Ice Data Center offered an initial assessment of Arctic sea ice that showed that the minimum extent for the year was the second lowest on record. Since then, NASA scientists have dotted the i’s and crossed the t’s and confirmed the finding. Joey Comiso, a NASA sea ice expert, said the continued pattern of low sea ice extents fits into the large-scale decline that has unfolded over the past three decades. “The sea ice is not only declining, the pace of the decline is becoming more drastic,” Comiso pointed out. “The older, thicker ice is declining faster than the rest, making for a more vulnerable perennial ice cover.”

So That’s What Happened to UARS

An old stalwart of NASA’s Earth-observing fleet, the six-ton Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS), came tumbling through the atmosphere in an uncontrolled reentry in late-September that generated a slew of headlines about the risks of being struck by falling space junk. Those risks, of course, are minuscule (about 1 in 21 trillion) and the handful of satellite pieces that did survive reentry ended up falling harmlessly into a remote area of the South Pacific in the general vicinity of Christmas Island. After its launch in 1991, UARS played a critical role in parsing out how chlorofluorocarbons, chemicals that used to be used widely as refrigerants, deplete ozone. UARS is gone, but for NASA the study of ozone goes on. Later this month, a new ozone-monitoring instrument called Ozone Mapper Profile Suite (OMPS) will launch as part of the NPOESS Preparatory Project.

Texas Drought Overstays Its Welcome

If you’re from Texas, you know this already. But for those who aren’t: the state has been embroiled in an extended heat wave and drought that has left large portions of the state on fire and caused billions of dollars in losses for farmers. If that’s not gloomy enough for you, climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon of the University of Texas warned that the situation isn’t likely to improve anytime soon. The drought could easily persist until 2012. The problem? The establishment of a new La Niña in the central Pacific Ocean, a phenomenon characterized by cooler ocean temperatures that leads to wetter than normal conditions in the Pacific Northwest and drier conditions in the Southwest.

Dramatic Arctic Ozone Loss

In April, the World Meteorological Organization announced that scientists had observed significant thinning of the ozone layer over the Arctic. That news turned heads because it’s the ozone layer over Antarctica that’s most prone to ozone loss. Recently, a research team associated with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory offered a more comprehensive assessment of the unusual spring thinning in the Arctic based on data collected by the Aura and CALIPSO satellites, balloon instruments, and atmospheric models. The bottom line: the upper atmosphere of the Arctic grew so cold this winter that ozone loss was severe enough that scientists say what amounts to a “hole” (five times the size of California) formed over the region and persisted for more than a month. Is climate change to blame? Sort of, but not exactly. Manmade chlorofluorocarbons drive ozone depletion (not the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide), but scientists say that global warming has likely exacerbated ozone loss because it cools the upper part of the atmosphere even as it warms the lower part. Confused? The Capital Weather Gang has a post that delves into the details.

It’s Earth Science Week. What are you doing to celebrate?

Our colleagues within NASA and at other institutions have organized a series of educational and outreach activities this week that showcase our science and the people behind it. Some highlights include:

+ A webcast with NASA’s chief scientist, Waleed Abdalati, from 1-2 p.m. Eastern Time on October 12. Teachers and students are invited to join Waleed Abdalati to share stories and perspectives on our ever-changing Earth. Participants can email questions during the webcast. Visit http://dln.nasa.gov/dln and scroll down to the DLiNfo Channel Webcasts to link to the webcast (no registration necessary).

+ Profiles of women making a difference in Earth science at http://women.nasa.gov/earth-science-week-special. The stars include: Cynthia Rosenzweig, who leads a group studying the impacts of climate change; Erika Podest, who studies wetlands and the global carbon and water cycles; Erica Alston, who focuses on fisheries and atmospheric science, including air quality; and Claire Parkinson, project scientist for the Aqua mission and a climatologist studying sea ice.

+ An introduction to the next Earth-science satellite, NPP, set to launch later this month. The National Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite System Preparatory Project will play a key role in studying climate change. Learn more about NPP and its polar bear mascot NPPy at http://npp.gsfc.nasa.gov/kids.html.

+ Short videos introducing Earth Science Week and NASA’s role in studying Earth, as well as educator resources and programs. Visit http://climate.nasa.gov/esw2011

Organized by the American Geological Institute and its federal and private partners, Earth Science Week was created in 1998 to help the public gain a better appreciation for the science and stewardship of our planet. The theme this year is “Our Ever-Changing Earth,” something you can observe daily here on the Earth Observatory.

“We invite you to join us online, explore our changing planet, and share this work with your students, family, and colleagues,” says Eric Brown de Colstoun, a scientist who also coordinates Earth science education for NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “You can also choose to reflect on how lucky we are to live on this beautiful and ever-changing planet, the home base from which we carry out our many explorations into the universe.”

More information about Earth Science Week can be found at http://climate.nasa.gov/esw2011/. Archived events from 2011 and years past can be found here.

Vishnu, an Earth Observatory reader, posed a great question after viewing “The Six-Million Mile View of Earth and Moon“:

“I’ve never seen a photo like that. Was the background beyond Earth ‘photoshopped’ to remove background stars, or is that angle so narrow and the background space so coincidentally ’empty’ that no visible stars are there to be seen?”

Our colleague D.C. Agle from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory worked with the Juno science team to provide this answer:

“The exposure time for the image — it’s actually three images: red, green and blue — was too short for any stars to be seen. Earth and the Moon were bright enough that a short-duration exposure was all that was needed. The brighter an object is, the shorter the exposure time required to capture an image of it. It’s similar to why you don’t really see stars in Apollo photos from the moon – the subjects being photographed were so much brighter than the background stars that the exposures weren’t long enough to capture the stars.

Here are two examples from the Cassini mission to Saturn showing long exposures that did capture stars. In both cases, the stars show up as streaks because of the relatively long exposures required to capture a good image of the moons.

+ Tethys in Eclipse

+ Iapetus by Saturn Shine

Cassini stays locked onto its target and actually turns very slightly during the exposures. Meanwhile the stars move slowly across the sky, and their images are smeared out as streaks.

Interestingly, the Voyager spacecraft took this remarkable image from about 7 million miles away in 1977. The difference is that Voyager was a survey and flyby mission, and its cameras were like long-range telescopes. Juno is an orbiter that will get extremely close to Jupiter every 11 days, and its camera is designed for that. It will take amazing wide-angle views from only a few thousand miles above the cloud tops. So that’s why Juno’s camera has a field of view about 130 times wider than Voyager, and thus why Eath seems so much smaller even though Voyager was a little farther away when it took its Earth-moon image.”

******************************************

Along those same lines, another reader (Norton) pointed out the lack of stars in a shot closer to Earth: “I was curious to see stars in this image of earth, yet in most other images the stars aren’t visible.

In one of your images of the day a week or two later, there are no stars visible. Is this solely due to how much light is captured by the camera and the stars are a weaker source; or is something else occurring that the stars aren’t visible?”

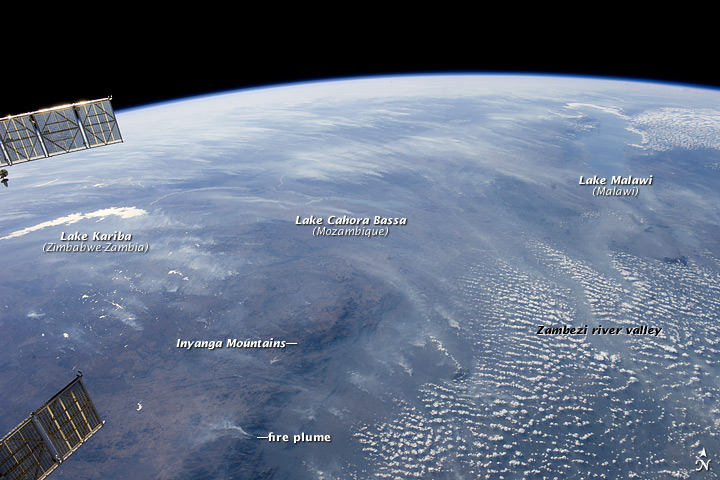

Our colleague Will Stefanov of the ISS Crew Earth Observations Team at NASA’s Johnson Space Center offered this explanation:

“It’s dependant on the camera settings, and to some degree the camera itself. The Nikon D3 cameras the astronauts often use are designed to be more sensitive in low-light situations, so you are more likely to capture some bright stars in the imagery. Images taken with long exposures and/or wide apertures will also record more starlight due to the greater amount of light on the camera sensor. Shorter exposure imagery of the Earth — the majority of daytime images — typically do not record stars as they are too dim compared to the brightness of the planet.

The astronauts generally follow a set procedure, with defined camera settings, for Crew Earth Observations imagery. But occasionally they will change those settings for a specific purpose or for personal experimentation. This can lead to images in which the stars are more visible for the reasons described above.

Floods Devastate Pakistan

For the second straight year, torrential monsoon-driven rains have swamped portions of Pakistan. The AFP reports that more than 200 people have been killed and thousands have fled their homes. Researchers associated with the MODIS instrument on the Terra satellite recently posted an eye-opening set of images that shows the condition of the swollen Indus River in early September in comparison to more normal conditions. Meanwhile, NASA researcher William Lau has published an interesting new study that shows last year’s floods in Pakistan were closely linked to large fires that occurred in western Russia around the same time.

Climate Science Marathon

Kick back and break out the popcorn. Al Gore’s Climate Reality Project has posted 24 hours of presentations and roundtable discussions about climate change. Reactions to the event have been predictably diverse. Commentators who regularly question the veracity of climate change have taken a dim view of the presentations, while those who regard climate change as an urgent threat have welcomed them. Despite having an unusually high tolerance for PowerPoint, I’ll admit that I have about 22 hours to go before getting through all of them. One segment caught my eye: NASA’s Drew Shindell explains how physics suggests a warming world will produce more extreme weather. Take a look starting at 37:35 of the Cape Verde video.

The Extreme Weather Connection

Speaking of extreme weather and climate science, Nature has an interesting piece about how some climate scientists have become less reluctant about linking extreme weather events to climate change. Nature recently published two studies highlighting just such connections. The journal also reports that a group of British and American researchers are laying the foundation for a system to assess in near-real time how much specific weather events are connected to climate change. “Attribution of extremes is hard — but it is not impossible,” Gavin Schmidt of the Goddard Institute for Space Studies told Nature.

[youtube 6Hv4S90UOBY]

See the Shrinking Arctic Sea Ice

The National Snow and Ice Data Center released preliminary numbers on the minimum extent of Arctic sea ice, calling this year’s minimum the second lowest on record. Other groups relying on slightly different data report this year’s sea ice minimum is a record low. At the end of the day, whether this year goes down as the lowest or the second lowest ice extent isn’t particularly important. The long-term trend is abundantly clear. Sea ice is retreating, and fast. NASA hasn’t weighed in officially with its numbers, but Goddard Space Flight Center’s Flickr page has posted striking video and stills of the 2011 ice loss.

Mars Research Has Earthly Applications

Looks like the time might be coming to trade in that dowsing stick for low-frequency sounding radar. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory announced that its scientists, in conjunction with colleagues from the Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research (KISR), have used sounding radar — developed for a mission to Mars — to successfully locate underground aquifers, probe variations in the water table, and identify locations where water flowed into and out of the aquifers. “This is a critical first step that will hopefully lead to large-scale mapping of aquifers,” said Muhammad Al-Rashed, director of KISR’s Division of Water Resources. Here’s a good video overview of the story.

Look Up: Here Comes UARS

NASA’s bus-sized Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite, or UARS, is poised to reenter Earth’s atmosphere on September 23rd or 24th. Much of the 12,500-pound (5,700-kilogram) satellite will burn up upon reentry, but Johnson’s Orbital Debris Program cautions that some pieces of the spacecraft could survive. Nobody has ever been injured by falling space junk, nor has any significant property damage ever occurred. Still, if you’re worried about being pelted, the Joint Space Operations Center of U.S. Strategic Command at Vandenberg Air Force Base will be posting frequent updates detailing when are where pieces might fall as the reentry date approaches. Meanwhile, read up on the considerable contributions the satellite made to science here.

Written by Jesse Allen, EO data visualizer…

Recently while doing something work-related (yes, really!), I stumbled upon a fascinating story. I found the Gates of Hell.

It turns out that they are in Turkmenistan. They were built — in a manner of speaking — by the former Soviet Union in 1971.

In 1971, Turkmenistan was a part of the Soviet Union. Not far from the village of Derweze (in Russian, it is Darvaza), a Soviet drilling rig hit an underground cavern, which subsequently collapsed and formed a deep pit, almost a hundred meters across. It was spewing toxic gases.

In order to contain the hazard, the gases were set alight, with the expectation that the gas would burn off in a few days. A few decades later, though, the pit is still on fire.

Natural gas continues to seep into the crater at a significant rate, sufficient to keep the lights on much the same today as when the match got tossed in (figuratively speaking). The Darvaza Gas Crater has since come to be nicknamed The Gates of Hell, and it has proven an unlikely and unusual tourist destination in the midst of the Kara-Kum Desert. Every desert really needs gas heat, after all.

Some have written and railed about what an environmental travesty it is to have all of that natural gas burning off. And certainly 40 years of open fossil fuel burning seems like no minor matter. But a little perspective is in order. It is worth pointing out that the Gates may well be no more dramatic than a single large gas-fired (or perhaps a moderate coal-fired) power plant, of which there are a great many in operation for 40 years or more around the world.

The pit might also be compared to any of a number of natural features, such as active volcanoes. There’s a constantly molten pit of lava emitting hot, toxic gases at the summit of Nyiragongo, for example, and it’s just as dramatic (maybe more) as the Gates of Hell.

Industrial accidents, malicious intent, and even natural events have lit fires that have burned for comparable periods elsewhere. Centralia, Pennsylvania, had to be permanently evacuated, for example, after a 1962 trash fire reached an underground coal seam that has been burning ever since. (Poisonious carbon monoxide still seeps out of the ground.) Retreating Nazi sailors set the Mine #2 alight near Longyearbyen in Norway’s Spitbergen Island in 1944, and that fire burned for some 20 years. Wikipedia offers a whole catalog of coal seam fires, some of which have been burning for a century or longer!

It’s hard to know when, or even if, the Darvaza Gas Crater might go out. But what I do know is that the Gates of Hell are not so interesting from a satellite perspective. The 100-meter-wide crater is certainly discernable in the moderately high resolution Advanced Land Imager (image above), and infrared emissions show heat coming from the flames.

But who knew the Gates of Hell would turn out to look, well, boring?

References

The Door to Hell – Burning Gas Crater in Darvaza, Turkmenistan

As the world reflects on the 10th anniversary of the September 11, 2001, attacks on the United States, the Earth Observatory team has been struggling with what to say and do. Like so many other media outlets, we felt compelled to say something, to show something.

Our data visualization team found this: a previously unpublished view of New York City on September 12, 2001 (below). It was captured 10 years ago today by the Advanced Land Imager on NASA’s Earth Observing-1 satellite. (Other satellite views are here and here. The space station view is here.)

But all of us were left cold by it. Science left us cold.

I have been searching for several days for an old quote, but it eludes me. The gist of the thought is this: You start with a group of organisms — robins, dolphins, ants, humans — and you have life to study, life force to study. With scientific tools, you can study individuals…dissect down to

anatomical systems (circulatory, neurological, etc.)…then to organs…tissues…cells…mitochondria and nuclei…compounds and molecules…atoms…electrons, protons, and neutrons…quarks. But somewhere along the way, you lose the “life” of the thing. (Lewis Thomas? Bill Bryson? Richard Feynman? If you know the source, please tell us.)

So it is sometimes with satellite photos. We can learn a lot about our environments, our niches, our human fingerprints on the Earth. But sometimes you lose the life along the way. When we thought about running the above photo as an Image of the Day, it felt unworthy of the moment. You can see a city, but you can’t see the loss, the humanity, the soul.

But science and satellites can show us something: We all have one home that we share. It is a beautiful, fragile, awe-inspiring place.

Songwriter Julie Gold captured the thought in “From a Distance” (performed here by Nanci Griffith):

From a distance the world looks blue and green,

and the snow-capped mountains white.

From a distance the ocean meets the stream,

and the eagle takes to flight.

From a distance, there is harmony,

and it echoes through the land.

It’s the voice of hope, it’s the voice of peace,

it’s the voice of every man.

Post from Paul Przyborski, EO programmer…

For the past few weeks, we have quietly implemented a new way of viewing images on Earth Observatory. Some of you may have noticed that there is now a “view image comparison” button on some of our Natural Hazards images, as well as on this Image of the Day. You can also click on the image above to jump to a slider view.

This particular interface is based largely on the “Before/After” plugin available at www.catchmyfame.com. We owe a big thank you to the web developer responsible for this plugin, Jason A., who was generous enough to let us to use his code and bring you a new way to compare remote sensing imagery .

Please take a moment to try the new feature and let us know what you think. If you are a developer or website owner looking for new ways to enhance user experiences, you may want to head over to Jason’s site.

[youtube a1FpqatXj6w]

Behold the Mesmerizing Flow of Antarctic Ice

The first complete map of the speed and direction of ice flow in Antarctica slid off Science’s presses last month and hit the media with a splash. The BBC, New York Times, Climate Central and dozens of other publications highlighted the news and linked to this striking visualization of Antarctic glaciers flowing thousands of miles from the heart of the continent to its coast. “The map points out something fundamentally new: ice moves by slipping along the ground it rests on,” said Thomas Wagner, NASA’s cryospheric program scientist. “That’s critical knowledge for predicting future sea level rise. It means that if we lose ice at the coasts from the warming ocean, we open the tap to massive amounts of ice in the interior.” The study also uncovered a ridge that runs east to west across the continent.

Faux Controversy of the Week

The web got ahead of the facts in August when a Guardian reporter came across a study in an obscure scientific journal that considered how an alien species would react to life on Earth. The resulting Guardian article – ominously headlined “Aliens may destroy humanity to protect other civilizations, say NASA scientists” – created quite a stir on the web, particularly because the scientists made reference to the possibility that increasing levels of greenhouse gases could attract the attention of hostile aliens. The problem: as NASA headquarters made perfectly clear in a series of tweets, the agency did not fund or any in any way sanction the research.

An Ocean Current Out of the Blue

The discovery that a long-suspected ocean current – the North Icelandic Jet – contributes a large amount of cold, dense water to the global ocean conveyor belt that regulates climate in the Northern Hemisphere has thrown a wrench into scientists’ understanding of how the ocean will respond to climate change. The existence of the current means the North Atlantic may be less sensitive to climate change than previously thought, Reuters reported. “We’ve identified a new paradigm,” said Robert Pickart of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and an author of a new study on the North Icelandic Jet. “We’re hypothesizing a new, overturning loop of warm water to cold.”

Foamy Wakes Deflect Climate Change

Can the foamy wakes left behind ships counteract global warming? A study led by Charles Gatebe of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center suggests the answer could be yes. Boats create fleeting trails of foamy water that can reduce global temperatures by reflecting sunlight more than the darker ocean water nearby, New Scientist reported. That said, don’t expect ship wakes to serve as a trump card against climate change. The cooling wakes produce is just a fraction of the warming caused by shipping’s carbon emissions. And, to complicate matters even further, the particles of ship exhaust can influence cloud development in ways that can also affect the climate.

Happy 20th, Alaska Satellite Facility

Satellites high in space tend to get the lion’s share of attention, but the data they collect mean little until they’ve gone through one of a network of eight ground-based data processing centers scattered across the country. NASA’s distributed active archive centers, or DAACs, transform raw data into sets that all Earth scientists can access and study. One of the DAACs, the Alaska Satellite Facility, just celebrated its 20th anniversary, the News Miner reported. According to that paper, the Fairbanks facility receives data that allows scientists to monitor volcano activity, sea ice coverage, deforestation, and glacier retreat.

Carbon Emissions on the Rise

The economy may feel like its ailing, but that hasn’t stopped carbon dioxide emissions in the United States from shooting up, the U.S. Energy Information Administration reported. In 2010, energy-related carbon dioxide emissions went up 213 million tons or 3.9 percent – the largest increase since 1988 when emissions rose by 218 metric tons or 4.6 percent. What’s behind the growth? Population went up, manufacturing (particularly energy intensive manufacturing) bounced back after the 2008-2009 recession, and a hot summer led to increased air-conditioning demand. Since 1990, Forbes reported, CO2 emissions in the U.S. have grown at an average annual rate of 0.6 percent.

We recently received this question from Jeff, a reader in Colorado:

We’ve been having lots of hazy days in Colorado. I’m sure it’s common over most of the U.S., Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. Most likely, it’s also over Europe.

I saw your images of fires burning in Russia. Could it be that a lot of our haze in the western U.S. and beyond, is due to these fires? I realize there are also many fires burning in the lower 48 states at this moment.

Would you be able to post information concerning the vast amount of smoke and pollutants that are now being created by mankind, and how that is directly affecting the process of climate change.

Jeff’s first question is one that air quality officials ask routinely. Is the pollution over my city from local sources that can be regulated, or does it come from somewhere else? Summer pollution can have many sources, both local and distant.

I sent the question to Gabriele Pfister, researcher at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. Gabriele has investigated how smoke travels and what impact it has on air quality far from the fires. She replied:

Around the world, ash and thick smoke from wildfires can fill the skies. While the smoke seems to disappear with distance from the fires, polluting gases and small particles that are invisible to the human eye can be carried away by global air currents. Over the past decade, satellite data helped reveal that pollution transport often occurs over hundreds and even thousands of miles, and long-distance transport has received increased attention due to the potential impact on the air quality of continents downwind.

Wildfires release a range of chemical species to the atmosphere, similar to pollutants emitted from human sources. These include the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide and methane, but also other air pollutants such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds, and aerosols. The gaseous pollutants also influence tropospheric ozone formation, a pollutant as well as a potent greenhouse gas.

Research on the transport of pollutants in the troposphere indicates that air pollution is not a local but a global problem. A good example for this is a study by Pfister et al. on the extreme wildfires that happened from June through August 2004 in Alaska and Canada. These fires produced approximately 30 teragrams of carbon monoxide, roughly equal to all the human-generated carbon monoxide for the entire continental U.S. during that same period. Using satellite data and models, researchers estimated that ground-level ozone increased by up to 25 percent in the northern continental United States, and by up to 10 percent in Europe.

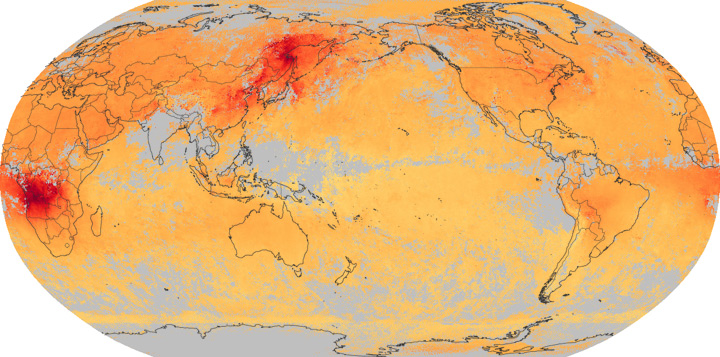

So, could Russian fires be causing hazy days in the United States? Let’s take a look at some satellite measurements. This image shows carbon monoxide, one of the constituents of smoke, in July 2011. Carbon monoxide is not visible, but it can combine with other pollutants to contribute to urban haze. It is also a harmful pollutant on its own.

The image was made with data from the MOPITT sensor on the Terra satellite. High concentrations of carbon monoxide are red and lower concentrations are yellow. (Regularly updated images are on the NEO web site.)

The Russian fires burned throughout July, and clearly they produced a lot of carbon monoxide. Carbon monoxide may also be coming from industrial processes in eastern China. Carbon monoxide concentrations are high across the North Pacific and into North America. Some of the gas over North America may be from the Russian fires, but intense fires in Canada probably contributed much more to air quality in the United States.

One of my favorite resources for tracking pollution in the United States is the Smog Blog. They have several posts discussing the Canadian smoke over the United States in July.

Jeff’s second question—how is pollution directly affecting Earth’s climate—is among the most important questions in climate science at the moment. The greenhouse gases released from fires will accelerate global warming. However, most pollutants act like a shade that cool the Earth by reflecting energy back into space. The exceptions are black carbon or soot particles, which absorb energy and make the atmosphere warm up while the surface cools. See Aerosols: Tiny Particles, Big Impact.

On the other hand, pollution has a few indirect impacts on climate. When particles settle on snow or ice, dark-colored pollution causes that surface to absorb energy rather than reflect it. This results in additional warming.

Pollution also affects clouds in a variety of ways, and clouds have a huge impact on global climate. In some cases, pollution causes clouds to be brighter and reflect more energy, causing cooling. In others, pollution can suppress the formation of clouds. Since clouds reflect energy and cool the Earth, the absence of clouds would cause warming. Right now, scientists don’t know exactly how the interaction between clouds and pollution will influence the climate.

We can be pretty sure, however, that global warming will impact pollution. Here’s what Dr. Pfister said:

About half of the world’s air pollution comes from wildfires, and a bad fire year can result in pollution from the fires circling the globe. Global warming is expected to cause earlier snowmelts, hotter temperatures, more frequent droughts, and more frequent and more potent fires. (Actually, this is already occurring.) And these fires release even more pollutants and greenhouse gases into the atmosphere that in turn might result in even hotter and drier weather and more fires.

Great question, thanks for writing Jeff!