The state of Punjab is known for being India’s breadbasket. Though relatively small, Punjab grows about 20 percent of the wheat produced in India and 10 percent of the rice.

One of the byproducts of such intensive food production is smoke. There are two main growing seasons in Punjab: one from May to September and another from November to April. In November, farmers typically harvest rice and sow wheat. After the harvest, they often set fire to leftover plant debris to clear fields for the next plantings, a practice known as stubble or paddy burning.

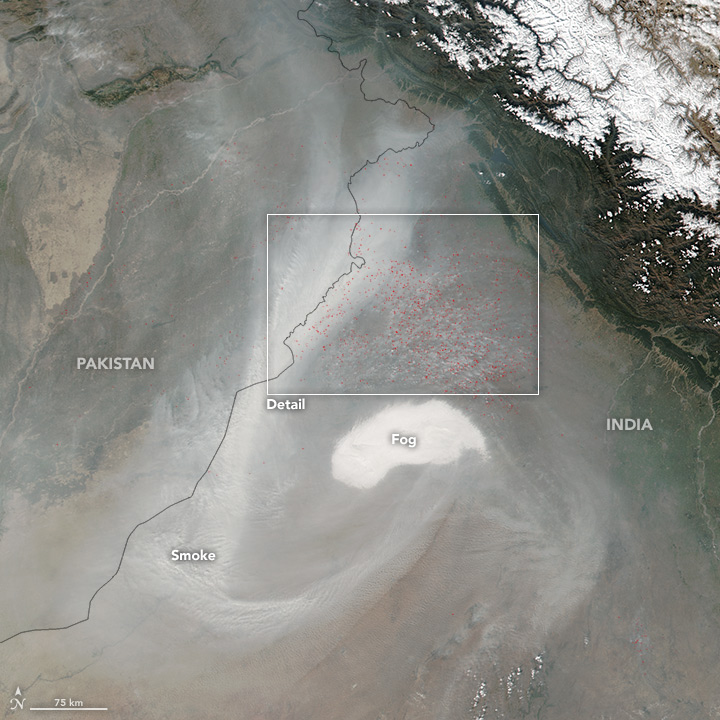

When the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the Suomi NPP satellite passed over the region on November 5, 2015, stubble fires were widespread. In the image above, red outlines show the approximate locations of active burning. Fields generally appear brown. See the lower image for a broader view.

Stubble burning is a relatively new phenomenon. Historically, farmers harvested and plowed fields manually, tilling plant debris back into the soil. When mechanized harvesting using combines became popular in the 1980s, burning became common because the machines leave stalks that are about one-foot tall. Burning the stalks is the quickest and cheapest way to clear them.

Satellites began to detect large numbers of active fires in mid-October. Normally extensive agricultural burning lasts for about three weeks. Although most of the haze appears to originate from the agricultural fires, other factors such as urban and industrial smog may also be contributing.

The fires release several types of particles and gases into the atmosphere, including smog-forming carbon monoxide, and nitrogen dioxide. Haze that forms over the Punjab rarely stays there. While the fires burn, smoke often blankets much of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, exposing millions of people in the densely populated plain to elevated levels of air pollution.

NASA image courtesy Jeff Schmaltz, LANCE MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC. Caption and image annotations by Adam Voiland.